Graduate student Kait Nascimento, a disabled single mother living on welfare benefits, says it took her 10 days to “freak out” about Goddard College’s closure this summer.

She learned in early April that her three years of coursework for a master’s degree in mental health counseling would not transfer to another school. She hoped to graduate in December. The former public high school Spanish teacher changed careers after two head injuries left her unable to stay in the classroom.

“What feels outrageous is they did not have this ironed out before they decided to close,” said Ms. Nascimento, 39. “I’ve been working very hard, and I can’t afford to push out graduation.”

Goddard, a self-identified liberal campus founded in Plainfield, Vermont, in 1938, moved classes online in January. It is part of a wave of mostly rural liberal arts campuses that have announced their closures after receiving billions of dollars in federal pandemic relief funding.

“The pace of closures is accelerating … because small private colleges are struggling with declining enrollment, rising costs, an inability to increase tuition revenue, and the end of federal pandemic relief funds that helped plug budget gaps,” said Robert Kelchen, head of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the public University of Tennessee-Knoxville.

“It is a function of basic economics,” said Gary Stocker, a former chief of staff at private Westminster College in Missouri and founder of College Viability, which evaluates campuses’ financial stability. “There are too many college seats and not enough college students willing to pay for them.”

The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit education news outlet, said at least one college per week from Jan. 1 through April 26 announced closures or mergers with other campuses. Among them were Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama, Fontbonne University in St. Louis and Notre Dame College in Ohio.

The pace of closures doubled from 2023, when a little more than two universities per month announced they would shutter, according to the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association.

“I think schools are worse off than they were before the pandemic because they never rebounded,” said Rachel Burns, a senior policy analyst for SHEEO, a group representing state officials in charge of public colleges. “They were artificially kept afloat by pandemic funding, but their enrollment numbers never recovered.”

In 2020 and 2021, the Trump and Biden administrations poured $77 billion of coronavirus relief money into higher education in three waves. Most colleges spent that money before the deadline last summer. The remainder received extensions expiring at the end of June.

Goddard College received $760,331 in relief funding that it spent by spring 2022, according to a report on the school website. Officials noted in April that enrollment had fallen from more than 1,900 in the 1970s to 220 this year, influencing a unanimous board vote to close.

Higher education groups say the recent college closures have hurt mostly minorities, older adults and Pell Grant recipients — all of whom make up the majority of college dropouts.

Downward trends

U.S. colleges have been closing or merging campuses since 2011, when enrollment peaked at 21 million students in more than 7,000 schools, according to the federal National Center for Education Statistics.

The pace of closures has accelerated since COVID-19 lockdowns. In 2021, about 5,900 colleges served an estimated 19 million undergraduate and graduate students, NCES figures show.

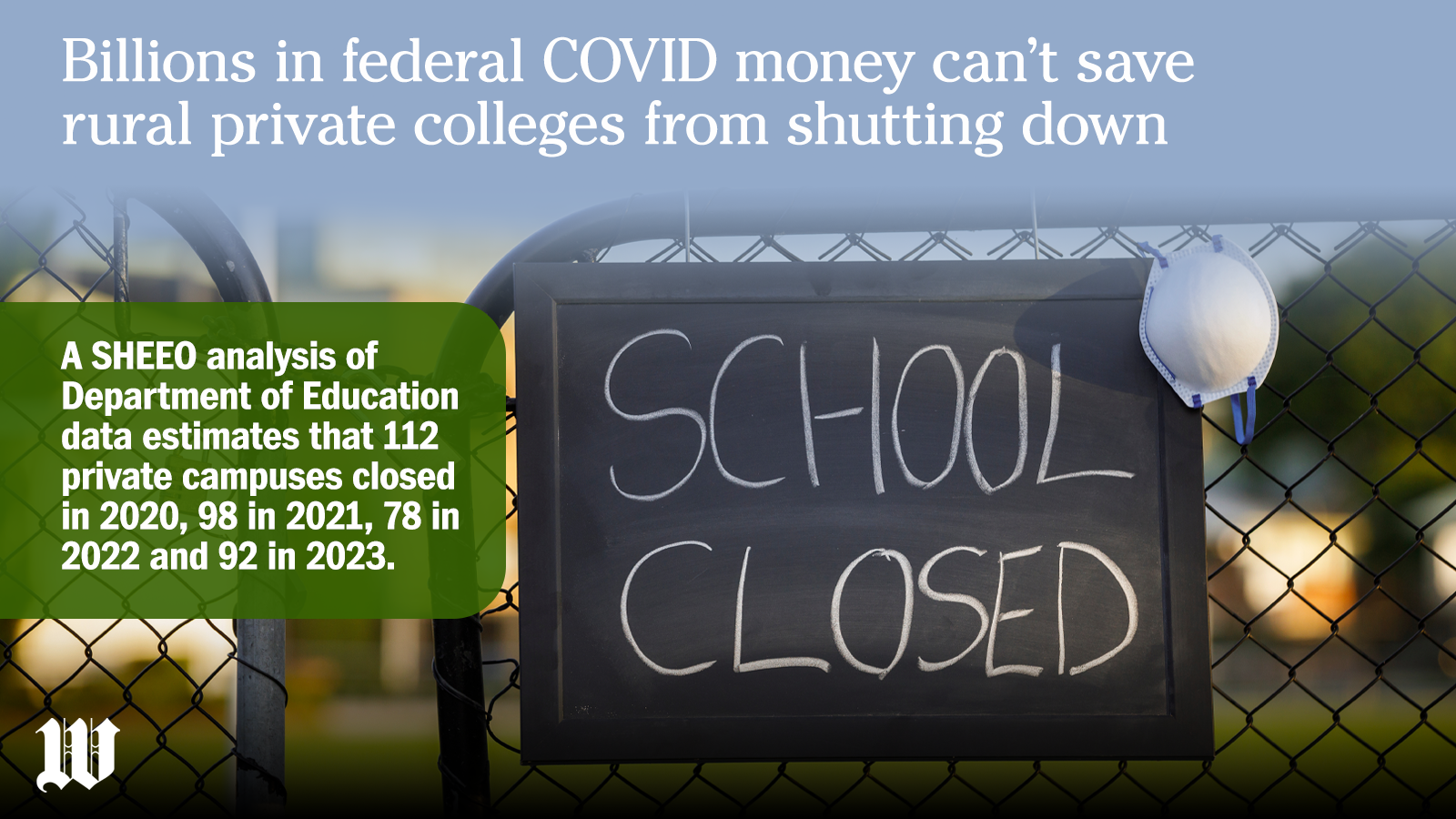

A SHEEO analysis of Department of Education data estimates that 112 private campuses closed in 2020, 98 in 2021, 78 in 2022 and 92 last year.

Although public funding shields state colleges from closing, a smaller but growing number of public systems have merged campuses. In 2022, Pennsylvania consolidated six rural colleges into two newly formed schools: Commonwealth University and PennWest University. In July, Vermont merged three similar campuses into the newly created Vermont State University.

Education Department statistics show that 10 public campuses merged or were absorbed in 2020, according to SHEEO. Two campuses did the same in 2021, followed by seven in 2022 and 16 last year.

SHEEO found that 861 higher education institutions ceased operating from 2004 to 2021. Most were small liberal arts schools, often founded in the 19th century in rural areas of the Midwest and East Coast.

“College closures hurt the economy because a lot of those colleges employ people from the local communities and create opportunities for students in their areas,” Ms. Burns said.

Decades of studies have cited the soaring cost of higher education as a factor in enrollment declines and related closures.

In online surveys that the Gallup poll and the nonprofit Lumina Foundation conducted from Oct. 9 through Nov. 16, 56% of never-enrolled and previously enrolled adults said cost was a “very important” reason they chose not to finish a college degree.

Higher education economists say declining birthrates have made it impossible to produce enough students to sustain hundreds of small colleges, many of which have anchored the economies of small towns for more than 100 years.

Public and private nonprofit colleges have competed for a dwindling number of applicants in recent decades.

Administrators have been preparing for a “demographic cliff” starting in the fall of 2026. The drop in the tally of 18-year-olds eligible to apply for college is expected to be sharper than usual because Americans started having smaller families during the Great Recession from December 2007 to June 2009.

Vanishing students

The shrinking number of 18-year-olds is the clearest indicator that the U.S. cannot sustain the roughly 4,500 colleges now eligible for federal aid, said Charles Goldman, a higher education economist at the Rand Corp. think tank.

“We will have a small number of relatively powerful institutions with a strong position in the marketplace and a large number of struggling institutions,” Mr. Goldman said. “I don’t think there’s going to be a relief from the demographic pressures. It’s going to make families think twice about attending less prestigious institutions where what they earn after graduation is not going to match the debt they take on.”

Other challenges facing small colleges include rising maintenance costs, a slowing pipeline of international applicants during COVID-19 travel restrictions and political tensions with China, and the relatively low value of rural real estate, which prevents campuses from boosting revenue by leasing space.

Most of the students at shuttered colleges never finish their degrees, education researchers say.

More than 40 million Americans have dropped out of college without finishing their studies, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The education nonprofit estimates the tally is growing as more schools close.

“Many of these schools had been anticipating a sharp recovery in enrollments after the pandemic ended,” said Doug Shapiro, executive director of the clearinghouse. “That hasn’t materialized, making it harder for them to hold out any longer.”

In an email, a Department of Education spokesperson urged students at shuttered schools to pursue their studies elsewhere.

“Students interested in continuing and completing their education elsewhere may want to speak with financial aid administrators at other schools about the students’ individual circumstances and possible next steps,” the spokesperson said. “Information about school closures and students’ options — including FAQs about transcripts, discharges, tuition reimbursement, and transferring credits — is available at StudentAid.gov/closures.”

Market competition

Experts predict tuition-dependent colleges that once flourished on a model of increasing enrollment will find it harder to compete with state-subsidized universities and community college certification programs over the next few years.

“Families are asking if the cost of a college education at a mediocre college is worth it,” said Michael Warder, a California-based nonprofit consultant and former vice chancellor of private Pepperdine University. “A good number of young people believe software, technology and AI are the future, and there are opportunities to learn online or on the job at tech companies.”

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center reported last month that 99,200 fewer students earned bachelor’s and associate degrees in the 2022-2023 academic year, a 2.8% drop and the second consecutive year of declines.

On the other hand, the center reported that “more students earned a certificate … than in any of the last 10 years.” A surge of 18- to 20-year-olds make up more than half of a 6.2% increase of 26,900 first-time graduates. That built on a 6.5% annual increase of 26,700 people in the previous academic year who earned their first certificates for trades such as machine repair, computer programming and accounting.

“Many [young people] conclude that the benefits of getting a college degree do not outweigh the cost,” said Lance Izumi, an education policy analyst at the free market Pacific Research Institute and past president of the board of governors of the California Community College. “They could … get a better payoff [by] working or focusing on career technical education that results in the development of a marketable skill.”

Stephen Miller, an economist at public Troy University, said small and middle-sized campuses long benefited from a “college enrollment boom” of rising demand that let them increase revenue by raising tuition and fees from 1970 to 2010.

He said those revenue boosts allowed schools to expand their “internal bureaucracies,” adding staff members with no higher purpose other than to “grow enrollment and build more buildings.”

“At some point, raising prices actually reduces revenue because of the students who can’t or won’t afford an increasingly expensive product,” Mr. Miller said. “A college has to offer something in exchange for tuition and fees, whether that is a well-paying job down the road, personal growth or powerful networking opportunities.”

Not all higher education depends on enrollment. In the halls of the Ivy League, elite private schools with large endowments have grown richer in recent years through large alumni donations, pandemic relief funds and federal research grants for math and science programs.

Nevertheless, some flagship state universities with extensive research programs have added students.

“While many smaller institutions are facing problems, many large state institutions continue to grow,” said Ronald J. Rychlak, a law professor and former associate dean at the University of Mississippi, which admitted a record-high 5,241 freshmen this fall.

“I think that reflects efforts by these universities to develop honors programs that meet the needs of top students while offering the ‘big campus feel’ of major sports, concerts and shows that smaller schools simply cannot provide,” Mr. Rychlak said.

Job competition

As more liberal arts colleges struggle to survive, schools have abolished humanities majors such as English and philosophy. They have also expanded courses in high-demand fields such as information security and computer programming.

Those efforts may be too little, too late.

A survey released this month by RedBalloon and PublicSquare found that 91% of small-business owners agreed with the statement that “colleges are creating unrealistic expectations among students about what their job and work life will be like post-graduation.”

“Colleges have lost their core mission,” said Andrew Crapuchettes, CEO of RedBalloon, a job listings website. “They’re producing graduates that aren’t ready for the workplace, and they are saddling these students with huge college debt.”

Accountant Donna Jackson, a former deputy controller for the Export-Import Bank of the United States, the federal government’s international credit agency, said recent college graduates also face increased competition for jobs in the tech industry from cheaper overseas labor.

The inability of small nonprofit schools to compete in that market puts even more pressure on them to close, she said.

“U.S. corporations have shifted their business models to importing skilled workers from overseas, where they can pay less for their workforce,” Ms. Jackson said. “In addition, many corporations have moved a lot of their corporate administrative functions to places like India and China with lower labor cost, resulting in fewer white-collar jobs.”

For more information, visit The Washington Times COVID-19 resource page.

• Sean Salai can be reached at ssalai@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.