The Justice Department inspector general’s office revealed Tuesday that the FBI and other federal law enforcement agencies stripped whistleblower agents of security clearances and pay without providing an opportunity to appeal the decision within a reasonable time frame.

The suspension policy for employees whose security clearances have been suspended, revoked or denied could leave them destitute and unable to return to their jobs or find alternative employment.

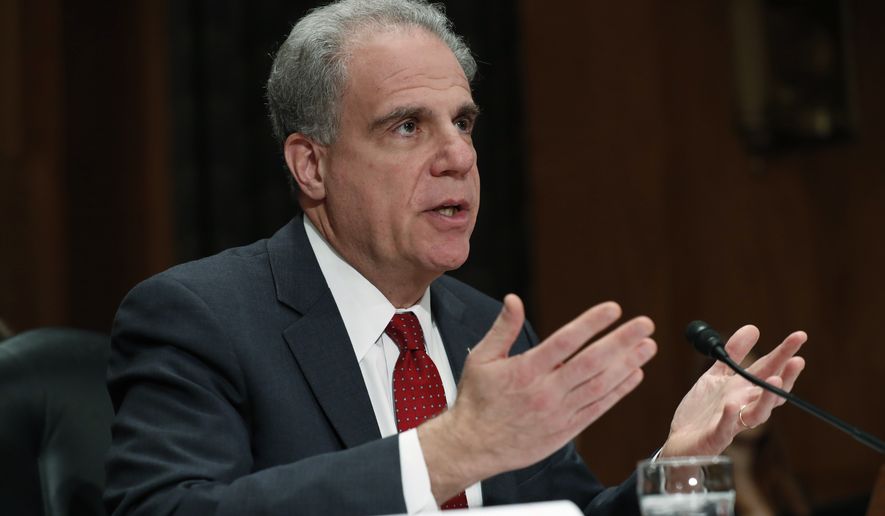

“This lack of appeal process is especially problematic at DOJ components that indefinitely suspend employees without pay for the duration of the security investigation and review process, which can sometimes last years,” Inspector General Michael E. Horowitz wrote in a memo to Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco.

“In many cases, it is financially unrealistic for an employee suspended without pay who claims retaliation ‘to retain their government employment status while [the security clearance review] is pending,’ given the length of time a security clearance inquiry often takes,” Mr. Horowitz said. “As a practical matter, therefore, the ability of an employee who has been indefinitely suspended without pay to retain their employment status can be rendered meaningless when that suspension lasts for a substantial period of time.”

Mr. Horowitz found similar concerns in the security clearance policy at the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

The FBI has been under scrutiny for its treatment of whistleblowers over the past two years after Congress received a flood of confidential disclosures about retaliation.

In a series of exclusive reports, The Washington Times detailed several cases of FBI whistleblowers who said bureau officials retaliated against them or punished them for political views by revoking security clearances, resulting in their suspension without pay.

The FBI refused to comment to The Times about the inspector general’s report.

Several FBI whistleblowers, including Marcus Allen, testified before House lawmakers last year about being punished by having their security clearances and pay revoked.

“It’s good that the inspector general called out DOJ’s systemic disregard for the law in this memo based on the case of Marcus Allen and other whistleblowers,” said Jason Foster, chairman of Empower Oversight, who is representing Mr. Allen. “But we are still waiting for his specific findings about the FBI’s retaliation against Marcus that we first referred to the IG more than a year ago.”

Mr. Horowitz faulted the Justice Department for not providing an inspector general appeal process for employees whose security clearances are suspended for more than one year and who say an agency is retaliating against them.

According to the inspector general’s office, federal law requires government agencies to establish a security clearance review process that “permit[s] … individuals [with a retaliation claim] to retain their government employment status while [the security clearance review] is pending.”

According to the inspector general’s review, the Justice Department policy also doesn’t restrict or provide guidance on how long an employee can be suspended indefinitely without pay while the component’s security review process is pending.

Mr. Horowitz said the Justice Department doesn’t consider “any practicable alternatives to indefinite suspension without pay during a security investigation for employees.”

He made four recommendations to address the problems:

• Let employees file a retaliation claim with the inspector general’s office when a security clearance review or suspension lasts longer than one year.

• Ensure that employees are notified in writing of their right to file a retaliation claim with the inspector general’s office when a security clearance review or suspension lasts longer than one year.

• Ensure that employees whose security clearance has been suspended, revoked or denied and who have made retaliation claims have an opportunity to “retain their government employment status” during a security investigation.

• Implement a process to “make every effort to resolve suspension cases as expeditiously as circumstances permit.”

The inspector general’s report said the FBI indicated that 106 of its employees have had their clearances suspended for six months or longer in the past five years. Of those 106 employees, the average time between suspension and a decision to revoke or reinstate the clearance was 527 days.

Whistleblower attorney Kurt Siuzdak said the FBI completes major corporate fraud cases in less than 500 days.

“I represent a substantial number of FBI employees, and I know of no instance in which the FBI has authorized a suspended employee to work for any private company,” he said.

The FBI has also refused to authorize its suspended employees to work for other government agencies that do not require security clearances, he said.

In the memo, Mr. Horowitz wrote, “The FBI, like the department, does not have a process that allows employees whose security clearance has been suspended for more than one year to file a retaliation complaint.”

Officials revoked Mr. Allen’s security clearance in May 2023 after he challenged FBI Director Christopher A. Wray’s March 2021 testimony about the presence of undercover federal law enforcement during the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol riot.

Mr. Allen said he and his family were financially destroyed by the FBI because he could not gain employment elsewhere or accept charitable contributions.

Another agent, Garrett O’Boyle, said he and his family were financially devastated and homeless after the FBI suspended him without pay for allegedly leaking information to media. Mr. O’Boyle disputes the FBI allegation.

FBI officials also revoked the security clearance and pay of FBI agents Kyle Seraphin and Stephen Friend, who also testified in May 2023 before House lawmakers. Both were bureau whistleblowers.

Responding to the inspector general’s report, the FBI said it would be challenging to identify practicable alternatives to indefinite suspensions without pay for employees with suspended security clearances.

The DEA told the inspector general’s office, “Employees who are indefinitely suspended without pay due to a security clearance suspension are still government employees — and therefore still have government employment status.”

The agency said it was working to develop language to notify employees of their right to file a whistleblower retaliation claim with the inspector general’s office when their security clearance review or suspension lasts more than one year.

The ATF acknowledged that nothing in its employment policies addressed the right of a suspended employee with a whistleblower claim to appeal to the inspector general’s office if the suspension lasts more than one year.

• Kerry Picket can be reached at kpicket@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.