President Biden plans to celebrate large drops in crime during his State of the Union address on Thursday, but that doesn’t reflect the experiences of people in cities such as the District of Columbia, Memphis, Tennessee and Dallas.

The progress also hasn’t reduced violent crime rates to pre-pandemic levels.

In the past week, Mr. Biden has gone on the offensive against Republicans who say Democratic policies have sparked a national crime wave. He met with big-city police chiefs at the White House and traveled to the southern border to try to change the narrative about crime.

The crux of Mr. Biden’s argument is a crime analysis by AH Datalytics that revealed an 11.8% drop in homicides nationally from 2022 to 2023. The research found that the numbers of rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults declined in 2023 from a year earlier.

If those numbers hold as the FBI collects more 2023 crime data from U.S. cities, they will mark the largest single-year drop in homicides since at least 1960. The FBI will release the official 2023 crime statistics this fall.

The double-digit decrease is less impressive considering that homicides in major cities remained dramatically higher last year than before the pandemic.

SEE ALSO: D.C.-area leaders stick by ‘sanctuary’ policies despite crimes tied to illegal immigrants

The nonpartisan Council on Criminal Justice reported a similar decline in homicides from 2022 to 2023 but found that homicides were 18% higher last year than in 2019.

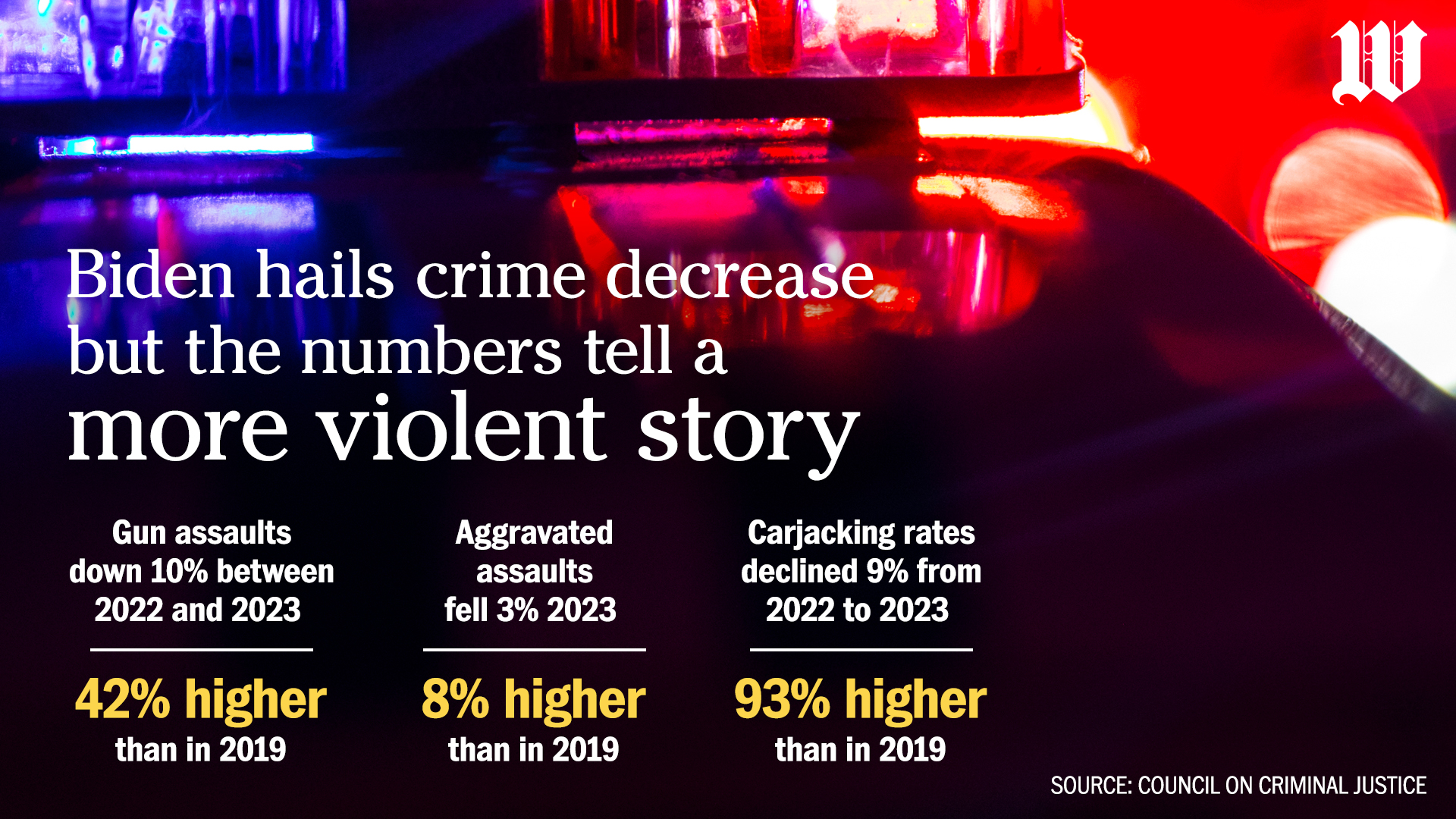

According to the council’s analysis, other violent crimes followed the same pattern:

• Gun assaults were down 10% from 2022 to 2023 but were 42% higher than in 2019.

• Aggravated assaults fell 3% last year but were up 8% from 2019.

• Carjacking rates declined 9% from 2022 to 2023 but were up a whopping 93% from 2019.

“Is the White House putting out correct crime statistics? It is correct based on a substack of data that an individual has put together for 2023. Is it a full picture of crime in the United States? No,” said University of Miami criminology professor Alex Piquero, a former director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics under Mr. Biden.

Jeff Asher, who co-founded AH Datalytics, noted that homicides in 2023 were up by more than double digits from 2019 but said the focus should be on the dramatic decline in recent years.

“I’m of the belief we should compare data to the recent yesterday,” he said. “The sharp decline from 2022 weighs more heavily for me than that it’s still up relative to 2019.”

Crime is a heavily localized phenomenon, and criminologists caution against painting a broad national picture based on cities’ data. A few cities with more than 200 homicides per year showed staggering increases last year.

The District recorded a 36% increase in homicides last year from 2022. Homicide rates jumped 27% in Memphis, 15% in Dallas and 7% in Kansas City, Missouri, during the same period, according to AH Datalytics’ numbers.

St. Louis and Baltimore recorded roughly 20% declines in homicides, but their totals were among the highest in the nation.

“If you look at D.C., Memphis and Oakland, no one is going to tell you crime is down,” Mr. Piquero said. “That might be true for a subset of cities at the national level, but not for those three cities.”

Even cities boasting about sharp declines in homicides last year have numbers well above 2019 levels. Homicides in Chicago dropped 13% from 2022 to 2023 but were 23% higher than in 2019, according to city data.

Philadelphia reported a 20% decline in homicides last year, but the rate was 16% above pre-pandemic levels.

The mixed results haven’t stopped Mr. Biden and other Democrats from taking credit for the decline and depicting the president as a crime-stopper who reversed the carnage of 2020.

Flanked by police chiefs last week, Mr. Biden said his administration chose “progress over politics and communities across the country are safer as a result of that policy.”

“Our plan is working,” Mr. Biden said.

Sen. Christopher Murphy, Connecticut Democrat, noted in a tweet last week that violent crime is down by “near record levels.” Last month, he linked Mr. Biden’s bipartisan gun bill to a 12% drop in homicides, though criminologists dismissed any connection.

“There is no way you can say that this law had any effect on crime because that means it would have had to affect crime in Memphis, Oakland and D.C., where it’s on the rise,” Mr. Piquero said. “You can’t say it affected nine cities and not the other five.”

The Biden administration maintained that violent crime rates declined because of its $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package, which boosted funding for local police departments and created job opportunities for youths in underserved communities.

Money from the relief package helped Detroit hire 200 additional officers, boost Milwaukee’s gun crime investigations and bolster Chicago’s community violence intervention programs.

Last week, Mr. Biden suggested that Republicans who opposed the relief package, dubbed the American Rescue Plan, stood in the way of his efforts to reduce crime.

Mr. Biden’s remarks were overshadowed by the killing of nursing student Laken Riley and other shocking crimes linked to illegal immigrants. Federal authorities charged a Venezuelan immigrant who was in the country illegally with Riley’s death. A man charged with murder in the death of a 2-year-old boy in Maryland and a man who shot police officers in the District were also in the country illegally.

Mr. Trump and other Republicans have seized on the headlines to claim Mr. Biden’s lax immigration policies fueled a crime wave.

The cases have become flashpoints in the immigration and crime debates, and voters are concerned.

Despite the reduction in violent crime from 2022, 63% of Americans say the crime problem in the U.S. is either extremely or very serious, up from 54% in 2021, according to a Gallup poll released late last year. More than 77% of Americans said the country had more crime in 2023 than in 2022, the poll found.

Criminologists debate the reasons for the drop in crime. One is that the world is more stable than it was during the height of the pandemic, and another is that related stressors have receded. Some cities shut down intervention programs during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

In 2020, calls to defund the police were on the rise. Some argue that police pulled back from law enforcement, but others say relatively few cities slashed budgets.

Mr. Asher said it’s “absolutely reasonable” to expect crime to reach pre-pandemic levels.

“Property crime fell in 2020 and 2021, and violent crime has been stable,” he said. “We should continue to try to learn what works and celebrate success.”

Ernesto Lopez, a research specialist at the Council on Criminal Justice, said politicians have made 2019 the flashpoint, but they should look at 2013 and 2014, when crime was at historical lows.

“Regardless of the political rhetoric, we are not where we were a decade ago, and that’s not ancient history,” he said. “There needs to be a serious conversation about how we get back to where we were because it wasn’t that long ago we were at a historic low.”

• Jeff Mordock can be reached at jmordock@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.