Raymond Kenneth Musgrove seemed to have hit on a perfect scam. He impersonated a Vietnam War veteran for more than 25 years, authorities say, to collect service-related disability benefits and health care under the man’s name.

The Veterans Affairs Department cut off benefits after the veteran’s death in 2018. Investigators say Mr. Musgrove called the VA and convinced officials that he was still alive and the dead man was the fraudster. The VA restarted the payments.

In 2021, the VA inspector general located the veteran’s headstone at Fort Sill National Cemetery and urged the department to cut off benefits. Court documents say Mr. Musgrove once again convinced the VA that the veteran, identified only by the initials J.M.C., was alive. Payments restarted again.

All told, authorities say, Mr. Musgrove walked away with more than $825,000 in bogus benefits, much of that paid after J.M.C.’s death.

Paying benefits to dead people is one of the more infuriating aspects of government spending, especially when it involves bureaucratic bungling or outright fraud.

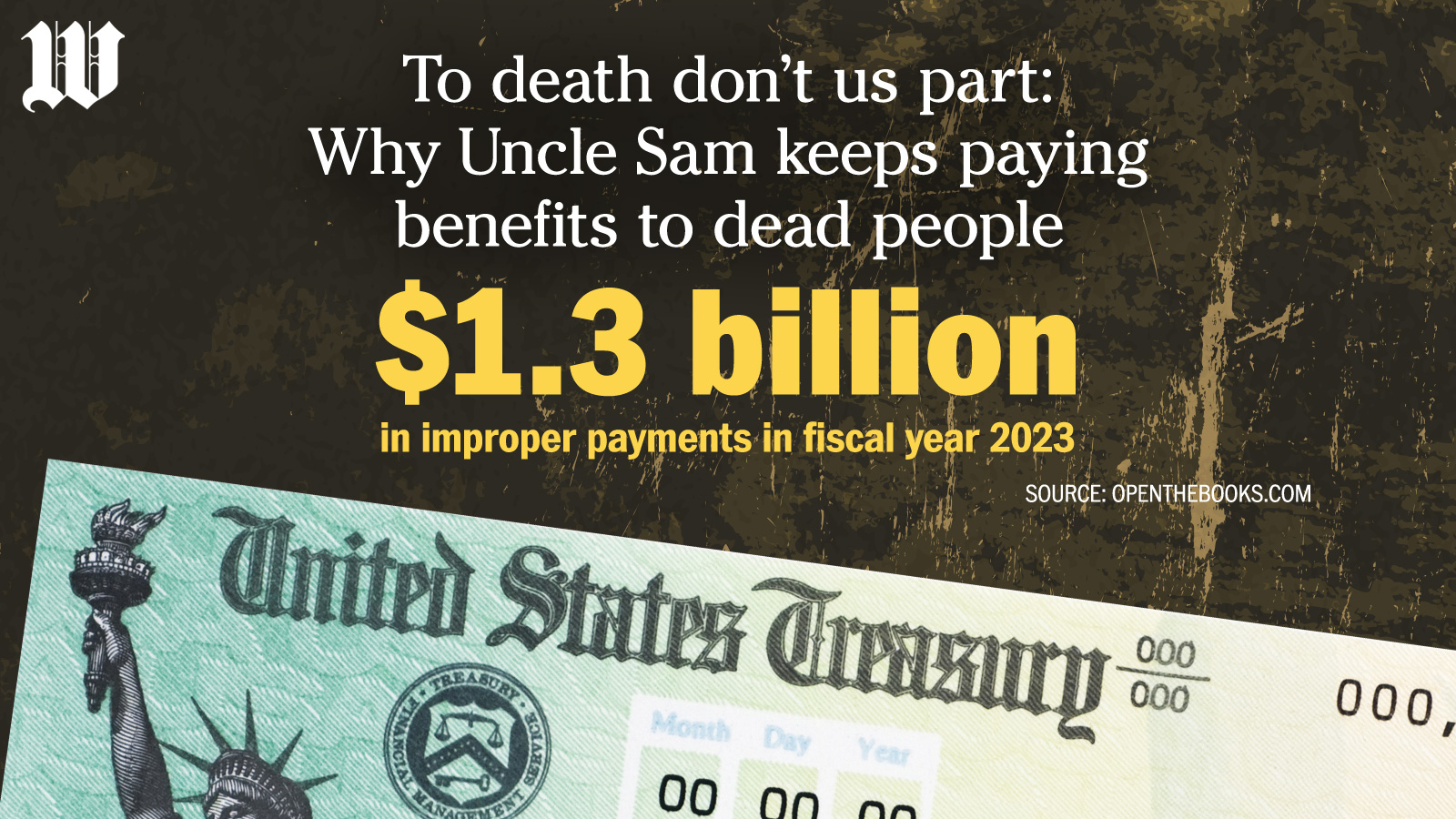

The government has trouble sorting out payments to those who have died, including disaster relief and farm subsidies. OpenTheBooks.com, a spending watchdog, said federal agencies self-reported $1.3 billion in improper payments to dead people in fiscal year 2023.

“Your corner grocery store has better internal financial controls than the major agencies of the United States federal government,” said Adam Andrzejewski, founder of OpenTheBooks. “The sheer amount of federal mistakes begs the question, ‘Is there anything that the federal government does well?’”

Perhaps the most infamous single example was the IRS’s distribution of $1.4 billion in pandemic relief checks in 2020 to 1 million people who died in 2019. The IRS said it felt bound to pay every person who filed taxes in 2019 regardless of whether they were alive or dead.

Thomas Schatz, president of Citizens Against Government Waste, said “improper payments” is government-speak for payments to dead people, but they are among the most galling to taxpayers.

“It’s the kind of wasteful spending that should be easier than the other types to stop. It shouldn’t be that hard to find out who’s deceased, and then you stop the payments,” he said. “It’s pretty poor management when the VA is literally shown the headstone of this guy that’s deceased.”

Irene Ferrin of Ohio collected VA benefits under the name of her mother, a widow of a World War II veteran, for 48 years after her death in 1973.

Ferrin lied to the VA on at least seven occasions to keep the benefits flowing.

The VA declined to answer questions about Mr. Musgrove, the man who twice persuaded the agency to restart benefits for a dead veteran. It cited the ongoing case.

In response to Ferrin’s case, the agency said it has checks in place to suss out extravagant claims.

“In 2019, VA instituted a match to be run periodically using data from other agencies to confirm whether Veterans and beneficiaries over the age of 100 are alive and entitled to benefits,” the department told The Washington Times. “In addition, VA annually reviews the records of all Veterans and beneficiaries receiving compensation, pension, or survivor benefits who are age 100 or older.”

That’s little comfort to taxpayers because the government rarely gets back fraudulent money it pays.

Ferrin, who was spared any prison time by the judge in her case, was ordered to repay $462,000. Given she was 76 at the time of her sentencing and had given up her job to provide round-the-clock care for her 80-year-old husband, her chances of repaying much of that are slim.

In the case of the IRS relief checks, the agency asked people to repay the money. After six months, just 60,000 of the 1 million payments had been returned, covering $72 million. That was about 5% of the money paid out.

Mr. Schatz said Social Security also has paid dead people.

Timothy Gritman was sentenced in February to 60 months in prison for collecting his dead father’s Social Security payments and New York state pension benefits.

Authorities say Ralph Gritman was last confirmed alive in September 2017 when Medicare showed him making an emergency visit to a hospital. Investigators figured he died soon afterward, but Timothy Gritman never reported the death and collected nearly $205,000 in benefits until October 2022.

New York investigators cut off benefits in 2022, but Gritman went so far as to whiten his hair and eyebrows to create a fake ID card to try to fool the state into thinking his father was alive. Gritman has not revealed the location of his father’s remains.

Gritman’s brazen fraud pales in comparison with that of George Doumar, who stole nearly a half-million dollars in Social Security benefits sent to his aunt, who died in 1977. The scam lasted until 2020.

Doumar’s attorney said he became trapped by how long he got away with the fraud. At some point, he figured he had crossed a line that would net serious consequences, so he was compelled to continue.

He admitted his fraud after investigators figured his aunt would have been the second-oldest person receiving Social Security benefits.

The delay may have paid off for Doumar. He was sentenced in 2021 to just three years of probation. Federal prosecutors asked the judge to go easy on the 78-year-old man because of the pandemic and his health issues.

He was ordered to try to pay back $443,358.30.

This week, Travis Gober was slapped with a 19-month term for running a business that bilked Medicare for payments for sleep studies that were never performed.

Among them were hundreds of studies for 19 people who were dead at the time of Gober’s reported treatment.

A federal investigator told the court that Medicare managed to block payments for the dead people but did pay out more than $1 million on sleep studies for live people who never had the treatments. A Medicare investigator visited Gober’s business office in 2016 and 2017 and found it shuttered. California suspended the business license in 2018, but Gober continued to bill Medicare and get paid.

Gober’s attorney said he was forced into the scam to pay off surprise company debts and then struggled for business during the pandemic emergency.

“This was truly aberrant conduct for an otherwise good person. And when an otherwise good person, like Travis Gober, errs in this manner — they punish themselves far more harshly than any sentence of imprisonment ever could,” said Christina M. Corcoran, the public defender who handled Gober’s case.

Gober asked for probation instead of prison time, but the judge sided with prosecutors in delivering the 19-month sentence. Gober’s brother Jeremy ran his own sleep clinics and pleaded guilty to health care fraud and identity theft. He is awaiting sentencing.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.