OPINION:

In the last days of East Germany, when government officials detected that their power was unraveling, they ratcheted up enforcement of the nation’s reporting laws. These laws made it a felony to know of a crime and fail to report it. It was also a crime to tell the person of whose crime you learned that you had done so. There was no right to privacy and no freedom of speech.

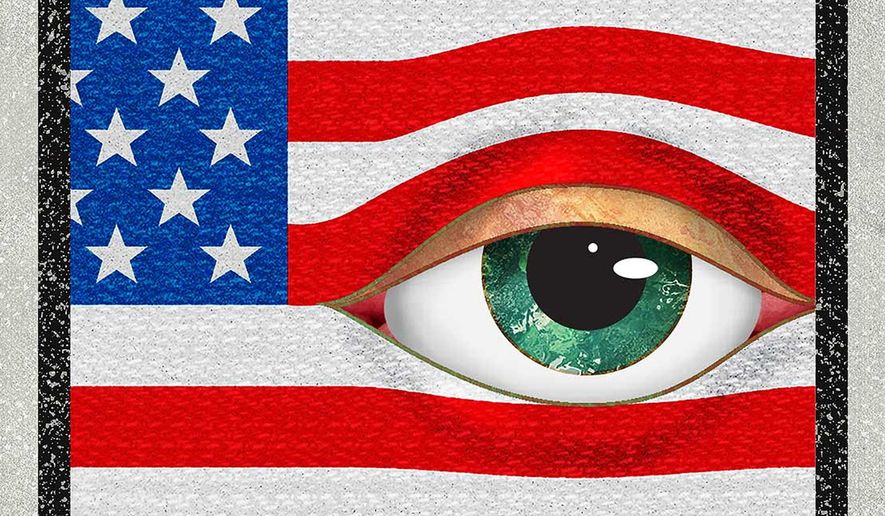

This Orwellian tangle resulted, of course, in many false reports of crimes. It also resulted in many prosecutions for failing to report crimes or warning others that they were being spied upon. As of this past weekend, we are headed to the same authoritarian place. Thanks to legislation that fell one vote short of demise in each house of Congress last weekend, the United States in 2024 will soon resemble East Germany in the late 1980s, where nearly everyone was a spy and no one could talk about it.

Here is the backstory.

The quintessential American right is the right to be left alone. Justice Louis Brandeis called it the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized people. It presumes that you can think as you wish, say what you think, read what you want, and publish what you say, that you can exclude whomever you wish — including the government — from your property and from your thoughts, and that you can do all this without a government permission slip or fear of government reprisal.

This natural right is also protected in the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, which requires a warrant issued by a judge based upon probable cause of crime before the government can invade your property or spy on you.

The warrant requirement serves three purposes.

The first is to force the government to stay in the lane of crime solving rather than crime predicting.

This concern was initially manifest in 1765 when the British government entered colonists’ homes with warrants issued by secret courts in London based on governmental need, not probable cause, ostensibly looking to see if the colonists had purchased government stamps as the Stamp Act required. The true goal of these forced entries was to search for revolutionary materials in order to help the government predict who might be planning the revolution that would come in 11 years.

The second purpose of the warrant requirement is to prevent fishing expeditions; hence, the Fourth Amendment also requires that the warrants specifically describe the place to be searched and the person or thing to be seized.

The third and most fundamental purpose of the warrant requirement is to reduce the right to privacy in writing. All people — even the federal spies themselves, now about 100,000 in number — want privacy. The Framers knew this and believed they had guaranteed it in the Fourth Amendment.

They were wrong.

After the abuses of the right to privacy orchestrated by President Richard Nixon and carried out by the CIA and the FBI in the Watergate era, Congress enacted the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which established a secret court to do to Americans what the British had done to the colonists — issue broad general warrants, based on whatever the government wanted and not specifying the place to be searched or the person or thing to be seized. Much of the intelligence community gave only lip service to FISA and used high-tech means to spy on people in the U.S. all the time.

When the courageous Edward Snowden, who had been both a CIA and National Security Agency agent, revealed the warrantless spying, instead of curtailing it, Congress made it lawful; unconstitutional, but lawful.

Section 702 of FISA expressly authorizes the feds to spy on foreign persons and those with whom they communicate, inside the U.S. and elsewhere, without warrants. That means that if a foreign person communicates with an American, the feds can spy on the American as well, without a warrant. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court has interpreted Section 702 to permit the feds to spy on communications with foreigners — even innocuous communications such as family chatter, ordinary commercial transactions, or academic or medical consults — and the Americans with whom they speak to the third degree.

Hence, if you email your cousin in Europe, the feds can warrantlessly capture all the fiber-optic traffic you generate, as well as all the traffic of everyone in the U.S. to whom you communicate, as well as all the traffic generated by all those to whom they communicate. If you do the math, you will see that these numbers of victims — Americans spied upon without suspicion, probable cause or warrants — can quickly reach the hundreds of millions.

The new Section 702 is worse for freedom than its predecessor. Though shortened to two years before sunsetting — these sunsets are a joke, since they never happen — the new 702 requires that any person in the U.S. who installs, maintains or repairs any fiber-optic system must assist the feds in using that system to spy on the person’s own customers. It also prohibits that person from speaking about this. What happened to freedom of speech?

It gets worse. The new Section 702 exempts members of Congress from the “thou shalt not tell.” So, if you or I or a member of the Supreme Court is spied upon by our cable installer, he cannot tell anyone. But if your representatives in Congress are spied upon, the cable installer and the spies will inform them. What kind of democracy is this? And if the cable installer does tell you or refuses to spy on you, the terrors of East Germany will come down on him.

Why do we permit Congress with a whimper to legislate away the freedom of speech and the right to privacy? Why do we repose the Constitution for safekeeping into the hands of those determined to kill it? Is it any wonder that cynicism about the government is so pervasive?

• To learn more about Judge Andrew Napolitano, visit https://JudgeNap.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.