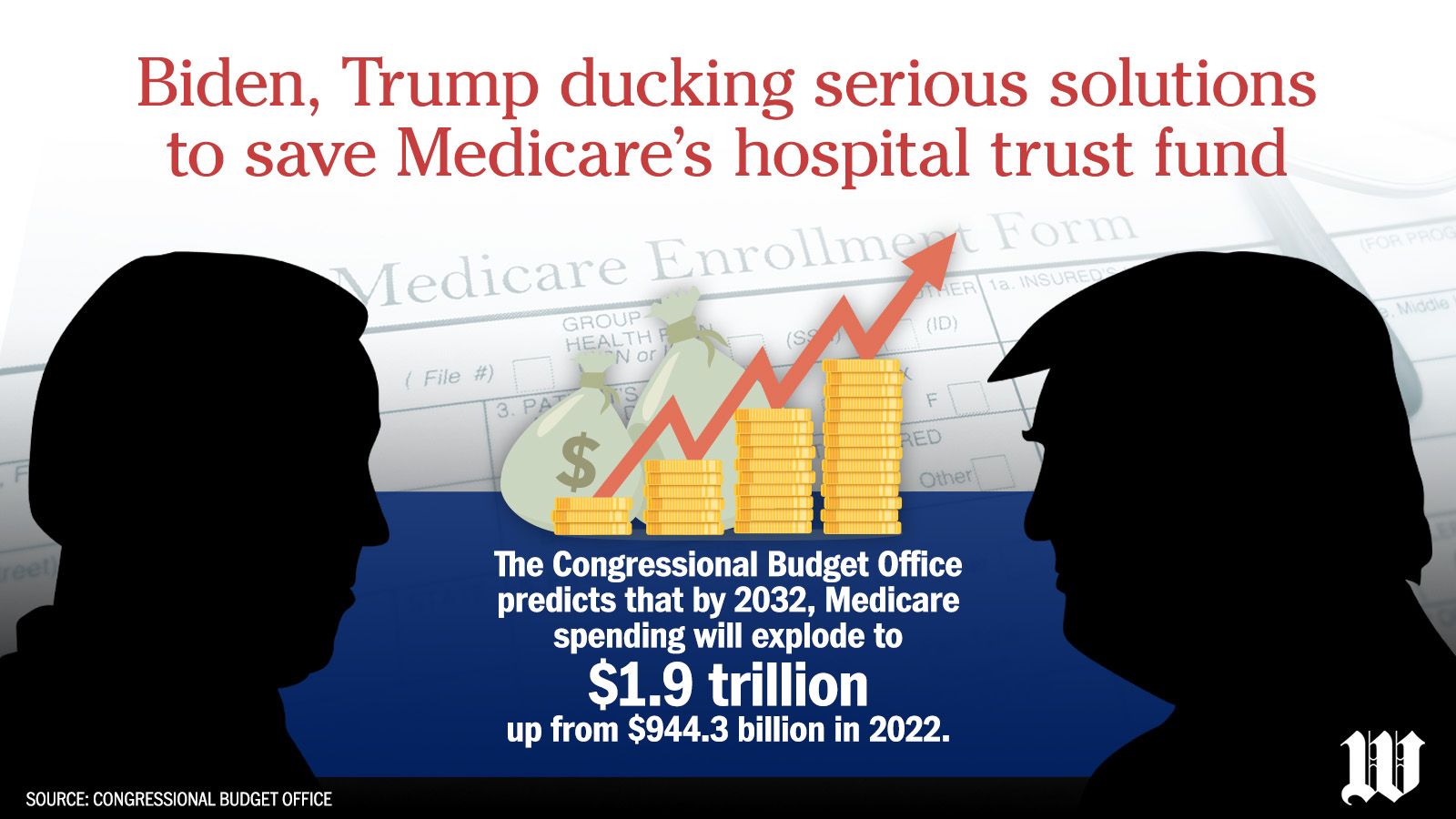

Medicare’s Hospital Insurance trust fund is projected to be depleted by 2031, but rather than propose serious fixes to the popular entitlement, both major political parties’ presidential candidates are attacking each other’s plans in search of political points.

Medicare spending is increasing much faster than the rate of federal tax revenue that supports it. The Congressional Budget Office projects that Medicare spending will explode to $1.9 trillion by 2032, up from $944.3 billion in 2022 and twice the current defense budget.

Once the fund is depleted, an automatic process or precedent will determine how the government will appropriate available funds or close the shortfall.

If the fund becomes insolvent, it would cover about 89% of the scheduled benefits. That would burden enrollees with tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills.

Some 62 million people are enrolled in Medicare. That number is expected to swell to 78 million by 2033.

A February poll by KFF found that 73% of voters want President Biden and former President Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, to talk more about Medicare affordability. The issue ranks ahead of the future of democracy (72%) and immigration (69%) among voters’ top concerns, according to the poll.

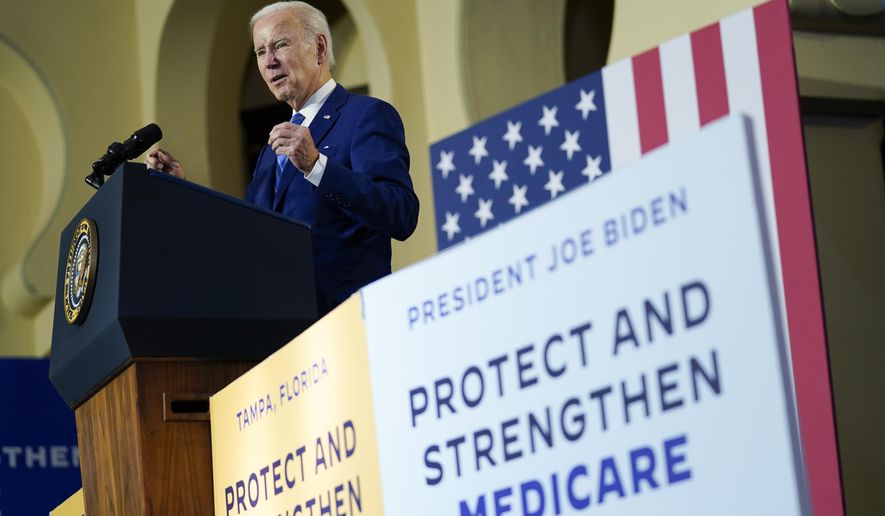

Yet neither Mr. Trump nor Mr. Biden has offered a realistic solution to the looming crisis. Mr. Biden has released a more detailed plan than Mr. Trump, who insists he wouldn’t cut benefits. The president’s proposal is based on heavy tax increases and is not expected to clear the Republican-controlled House.

“This is going to be a tidal wave that is going to overwhelm the economy with debt and will make decisions about defense spending and welfare seem pretty irrelevant. Biden and Trump are really just trying to wish the problem away,” said David McLennan, a Meredith College professor who teaches health care policy.

Mr. Biden’s budget proposal for fiscal 2025, released in March, calls for stabilizing Medicare by increasing taxes on the wages, investment gains and self-employment income of people earning more than $400,000 annually.

The White House predicts the tax increases will keep Medicare solvent for 25 years. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal agency that oversees the program, said the plan would extend the trust fund’s solvency “indefinitely.”

Mr. McLennan said the long-shot cash infusion wouldn’t solve the program’s structural problems.

“Even if everything breaks Biden’s way and Democrats control both chambers, the tax increases are a finger in the dike of a dam that has a lot of water behind it,” Mr. McLennan said. “Taxing the wealthy is Biden playing to his base, not a serious policy discussion.”

Mr. Biden persuaded Congress to pass his massive climate, health care and tax legislation known as the Inflation Reduction Act. The law authorizes Medicare to negotiate prices with drug manufacturers to reduce participants’ out-of-pocket costs.

The law affects 10 drugs that treat heart disease, certain cancers, diabetes, autoimmune disorders and other conditions. In 2022, the 10 medications cost Medicare $45.6 billion and enrollees $3.4 billion in out-of-pocket costs, according to White House data.

It also caps prescription drug costs for seniors on Medicare at $2,000 a year, no matter the total cost.

Pharmaceutical companies blasted the proposal as price-fixing by “government bureaucrats” that could harm research and development. The companies said they were forced to participate in the negotiations or otherwise face steep penalties or withdraw from the Medicare and Medicaid markets.

Mr. Trump has yet to lay out his plan to keep Medicare afloat or indicate that he would raise taxes to finance the program.

Trump campaign spokesman Steven Cheung did not respond to questions about when he would reveal his plan or what would be on the table to prevent benefit cuts.

On CNBC in March, Mr. Trump said there are “tremendous bad management of entitlements” and “tremendous amounts of things and numbers of things you can do,” but he offered no specifics. He suggested that poor management and theft were raising the costs of entitlements, and then he changed the topic.

“President Trump has never really enunciated a path to make major changes with Medicare,” said Stephen Parente, a chief economist for health care policy in the Trump administration who now teaches at the University of Minnesota. “It’s just not a topic he wants to weigh in on because he’s just not a traditional conservative in the way of a Republican you would traditionally see.”

During his presidency, Mr. Trump’s budgets didn’t call for Medicare cuts. Instead, the White House proposed lower payments to providers and suppliers through new incentives and a lower inflation benchmark.

The proposals were similar to Obamacare, which extended the solvency of Medicare by lowering payments to hospitals and insurers in exchange for more customers. He also proposed lowering prescription drug costs by allowing Medicare to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies.

Like his proposed Social Security reforms, Mr. Trump never pressed Congress to act on his Medicare plans, and they never became law.

An influential group of House Republicans submitted a proposal in March to restructure Medicare.

The Republican Study Committee, a group of more than 170 House Republican lawmakers that counts Speaker Mike Johnson of Louisiana among its ranks, outlined a significant overhaul to the popular but expensive entitlement.

The lawmakers call for converting Medicare to a “premium support model,” similar to a proposal that House Speaker Paul D. Ryan, Wisconsin Republican, laid out years ago. Under the Republican plan, traditional Medicare would compete with private plans and beneficiaries would be given subsidies to shop for the policies of their choice.

Whether the proposal will advance is unclear without Mr. Trump’s endorsement.

The size of the subsidies would be tied to the “average premium” or “second lowest price” in a particular market.

Mr. Biden called the proposal “extreme” and said it would raise prescription drug costs. He vowed to stop it.

Experts say the government could implement fixes beyond cutting benefits or raising taxes. Officials could move some of the services in Medicare Part A, the hospital fund, to Medicare Part B, which pays for necessary and preventive services. That would mean some Part A services that are 100% covered could be subject to the Part B deductible unless the beneficiary has a Medigap or Medicare Advantage plan.

“You could do that, but the question is: What would you move over?” Mr. Parente said.

The government could also reduce Medicare payments to some or all Part A providers.

Mr. Parente advocated for a “market choice” model of Medicare that would empower seniors to choose between the traditional fee-for-service Medicare and privately administered Medicare Advantage plans.

It would rely on free market competition among private insurers to reduce the costs of health care by empowering Medicare enrollees to shop for plans themselves.

The proposal could save the federal government an estimated $1 trillion over the next decade.

• Jeff Mordock can be reached at jmordock@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.