It was the most popular opening for the first three centuries of modern chess. Paul Morphy relied on it heavily during his meteoric rise to world supremacy in the mid-19th century. Bobby Fischer claimed to have definitively refuted it after a famous loss with Black to nemesis Boris Spassky 12 years before their epic title match.

And still the King’s Gambit lives on.

The ultimate Romantic opening is a rare visitor to top-level chess these days, but it still has its champions — and it still retains its sting. Russian GM Ian Nepomniachtchi risked the gambit in a critical match at the inaugural World Rapid Team Championships in Germany last month against veteran compatriot GM Peter Svidler. Twenty-two moves later, Black was stopping the clocks and tipping his king.

Having surprised his opponent (and disconcerted his teammates) with his opening choice, Nepomniachtchi scores a second small victory with Svidler’s choice of 3…Ne7!?, a relatively rare way to meet the gambit. (Fischer’s notorious “bust” of the opening led with 3…d6, with Bobby’s main line continuing 4. d4 g5 5. h4 g4 6. Ng5 f6 7. Nh3 gxh3 8. Qh5+ Kd7 9. Bxf4 Qe8! 10. Qf3 Kd8 “and Black wins easily;” subsequent praxis has shown things are not quite so simple.)

White gets the open game he craved, and by 13. Qxd2 0-0 14. 0-0-0, while he hasn’t won his gambit pawn back yet, Nepo has the better pawns, the safer king and enough positional compensation to be at least equal. Black has been walking a tightrope, and White’s clear initiative and the faster rapid time controls quickly force Svidler to lose his balance.

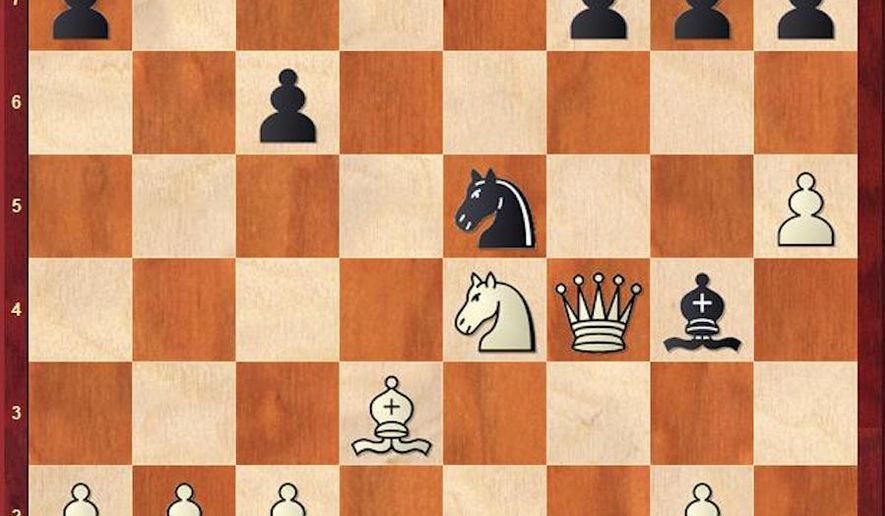

Thus: 14…Bg4?! (Bf5 puts up a tougher fight) 15. h5! Ne5 (Bxd1? 16. hxg6 Bg4 17. Qxf4 Be6 18. Rxh7 fxg6 19. Qh2, with a monster attack) 16. Qxf4 Qb8? (see diagram; overlooking a tactical trick, Black still is in the game after 16…Re8 17. Be2 Qc7! 18. Qf2 Rab8) 17. Nd6!, and the knight is immune because of 17…Qxd6 18. Bxh7+ Kxh7 19. Rxd6. White now threatens 18. Bxh7+! Kxh7 19. h6 g6 20. Qxe5 Rb8 21. Qf6 Qc7 [Be6 22. Nxf7 Bxf7 23. Qxf7+ Kh8 24. Qf6+ Kh7 25. Rd7+ and mate next] 22. Nxf7, winning, and a reeling Svidler goes down to quick defeat.

The finale: 17…f6 18. Qe4 g6 (Nxd3+ 19. Rxd3 f5 20. Qe6+, and the classic Philidor’s Mate is on tap after 20…Kh8 21. Nf7+ Kg8 22. Nh6+! Kh8 23. Qg8+! Rxg8 24. Nf7 mate) 19. hxg6 hxg6 20. Rh6! Qxd6 (Kg7 21. Rxg6+ Nxg6 22. Qxg6+ Kh8 23. Qh7 mate) 22. Rxg6+, and Black resigned as the rook and minor piece are no match for the White queen in lines such as 22…Nxg6 23. Rxd6 Ne5 24. Rxc6! Nxc6 25. Qxg4+ Kh6 26. Bd3 Rg8 27. Qf4+ Kg7 28. Qc7+ Kf8 29. Qxc6.

—-

Spassky rates as one of the King’s Gambits great modern champions, if only because of his brilliant victories with the opening over the likes of such great grandmasters as Yuri Averbakh, David Bronstein, Lajos Portisch and, yes, Fischer.

Even after losing the world crown to Fischer in 1972, Spassky still trotted out the gambit on memorable occasions, including a brilliancy win against another rising American star, GM Yasser Seirawan, in the 1985 Candidates tournament in Montpellier, France. It would be interesting to know if Svidler was familiar with this game, as Black here adopts the same wishy-washy 3…Ne7 sideline and meets the same grim fate.

The party starts early for White when Black tries too hard to hold the gambit pawn: 5. Nc3 dxe4 6. Nxe4 Ng6?! 7. h4! (wasting no time putting the question to the defending knight, as 7…h5 is too positionally compromising) Qe2? (neither 7…Nc6 8. h5 Nge7 9. Bc4 or 9. Bxf4 isn’t exactly good for Black, but either line would at least sidestep Spassky’s stunning riposte) 8. Kf2!!, making Black’s queen look foolish as 8…Qxe4?? 9. Bb5+ Kd8 10. Re1 Qd5 11. Re8 is mate.

It turns out the White king is perfectly safe on f2, while the Black monarch will never find a secure harbor after 8…Bg4 9. h5 Nh4 (relying on the pin on the White knight, but Seirawan’s pieces are getting seriously misplaced) 10. Bxf4 Nc6 11. Bb5 (Rxh4!? Bxf3 12. Qxf3 Qxh4+ 13. g3 Qe7 14. Re1 was also very strong here) 0-0-0 12. Bxc6 bxc6 13. Qd3 — White has recovered the gambit pawn, Black’s queenside pawns are a mess, and Spassky still enjoys a strong lead in development; Black’s game may already be beyond salvation.

As in the first game, Black has to surrender his queen just to avoid an even more disastrous fate on 17. Qxc6 Rxd4 (giving up the exchange with 17…Rd6 18. Bxd6 Qxd6 19. Qxd6 Bxd6 20. Ne4 also is just winning for White) 18. Rae1 Rxf4 (Qd8 19. Re8 Qd5, and White can choose between 20. Na6 mate and 20. Bxc7 mate) 18. Qb5+ Ka8 20. Qc6+ Kb8 21. Rxe7 Bxe7 22. Rd1, and, as in the Nepomniachtchi game, the White queen is far too strong for Black’s rook and minor piece.

After 27. Qa4! (threatening both the a-pawn and 28. Qg4+ Kb8 29. Qxg7) g5 28. Qxa7 Rf4 29. Qa6+ Kb8 30. Qd3 Be7 31. Qxh7 g4 32. Kg3, Black resigns as he has lost two more pawns and it’s hopeless in lines such as 32…Rxf3+ 33. Kxg4 Rf2 34. Qh8+ Kb7 35. Qe8 Bd6 36. h6, and the passed pawn will soon cost Seirawan even more material.

(Click on the image above for a larger view of the chessboard.)

Nepomniachtchi-Svidler, World Rapid Team Championship, Duesseldorf, Germany, August 2023

1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Nf3 Ne7 4. d4 d5 5. Bd3 c5 6. Nc3 cxd4 7. Nxd4 dxe4 8. Nxe4 Ng6 9. h4 Nc6 10. Nxc6 bxc6 11. Qe2 Bb4+ 12. Bd2 Bxd2+ 13. Qxd2 O-O 14. O-O-O Bg4 15. h5 Ne5 16. Qxf4 Qb8 17. Nd6 f6 18. Qe4 g6 19. hxg6 hxg6 20. Rh6 Qxd6 21. Bc4+ Kg7 22. Rxg6+ Black resigns.

Spassky-Seirawan, Montpellier Candidates, Montpellier, France, October 1985

1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Nf3 Ne7 4. d4 d5 5. Nc3 dxe4 6. Nxe4 Ng6 7. h4 Qe7 8. Kf2 Bg4 9. h5 Nh4 10. Bxf4 Nc6 11. Bb5 O-O-O 12. Bxc6 bxc6 13. Qd3 Nxf3 14. gxf3 Bf5 15. Qa6+ Kb8 16. Nc5 Bc8 17. Qxc6 Rxd4 18. Rae1 Rxf4 19. Qb5+ Ka8 20. Qc6+ Kb8 21. Rxe7 Bxe7 22. Rd1 Rf6 23. Nd7+ Bxd7 24. Qxd7 Rd8 25. Qb5+ Kc8 26. Rxd8+ Bxd8 27. Qa4 g5 28. Qxa7 Rf4 29. Qa6+ Kb8 30. Qd3 Be7 31. Qxh7 g4 32. Kg3 Black resigns.

• David R. Sands can be reached at 202/636-3178 or by email at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

• David R. Sands can be reached at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.