The House this week will vote on a bill that would permanently place every form of illicit fentanyl on the most restrictive list of drugs to ensure that traffickers of the deadly synthetic opioid cannot tweak chemical compounds and avoid prosecution.

Republican leaders say the U.S. cannot dither in its fight against the fentanyl crisis, which kills tens of thousands of Americans each year. The HALT Fentanyl Act, which is scheduled for passage on Thursday, would keep fentanyl-related substances on the Schedule I list of drugs when temporary scheduling authority expires at the end of 2024.

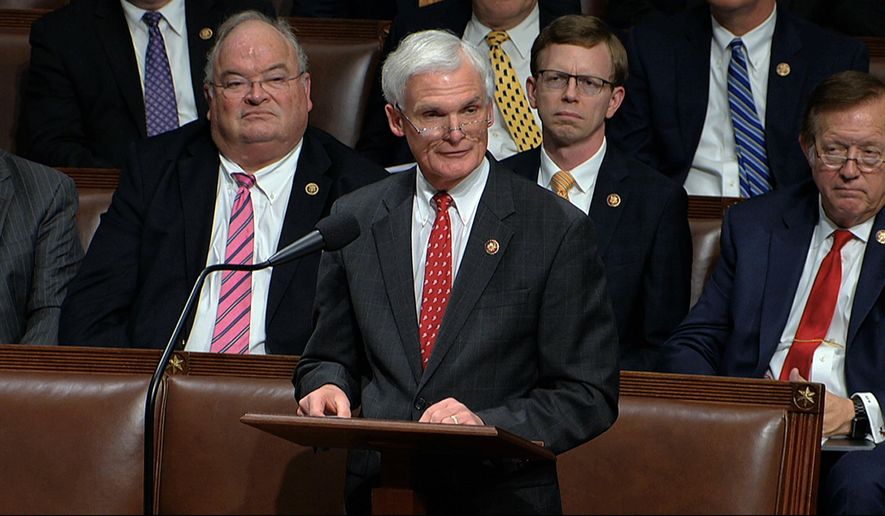

The Drug Enforcement Administration recently called permanent scheduling its “number-one priority for this year” because it is too easy for traffickers to manipulate synthetic opioids and then claim they are acting lawfully, Rep. Bob Latta, Ohio Republican and lead sponsor of the bill, told The Washington Times.

“All [traffickers] have to do is change a little of the analog in this stuff and say, ‘Well, it’s not fentanyl.’ We have to make sure this is ‘fentanyl substances’ to make sure this is all picked up and get people convicted on this stuff,” Mr. Latta said. “This is going to cover everything.”

Experts say permanent scheduling would result in more efficient prosecutions and stiffer penalties under guidelines from the U.S. Sentencing Commission and send a signal to China and Mexico that the U.S. is serious about tackling the fentanyl problem as it pressures those nations to do more.

The House vote will be thorny for Democrats and President Biden. They say abuse of permanent scheduling is a top priority but fear that the Republican bill, as written, will impose mandatory minimum penalties that emphasize incarceration over treatment. They hope for a compromise when the bill heads to the Democratic-led Senate.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl has a legitimate use as a pain treatment for cancer sufferers and other patients. It will remain a Schedule II drug under the House bill.

Yet Mexican cartels are flooding the U.S. with an illicit form of fentanyl that is often made with precursor chemicals from China.

Fentanyl is the No. 1 killer in a broader U.S. overdose crisis that killed 109,680 people in 2022, according to provisional data released Thursday. Roughly 70,000 of the 107,000 overdose deaths in the U.S. were linked at least in part to fentanyl in 2021, the most recent year for which complete data is available.

Illicit fentanyl is made in clandestine labs and features several chemical cousins. It is difficult for U.S. laws to keep up with every form, so the HALT Fentanyl Act seeks to cover all illicit supplies.

The Congressional Budget Office released an analysis Thursday that underscored the bill’s role in prosecuting drug offenders.

To proceed with criminal cases, “prosecutors must prove that such drugs meet specific criteria related to chemical structure and psychoactive effects. By placing all FRS in Schedule I, [the House bill] would lower the burden of proof in certain cases, thus increasing the likelihood of conviction,” the budget scorekeepers said.

Rep. Frank Pallone of New Jersey, the ranking Democrat on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, will speak in opposition to the bill during a House Rules Committee meeting Monday that sets the table for floor action and possible amendments.

“This bill doubles down on mandatory minimums. I think it’s fair to say this bill attempts to incarcerate our way out of a substance abuse crisis,” said C.J. Young, a spokesman for Energy and Commerce Committee Democrats.

The White House is fine with minimum penalties for fentanyl offenses that involve bodily harm or death, but the administration and Democratic allies want to exempt quantity-related fentanyl offenses from mandatory criminal penalties. They say judges need flexibility.

They also say the bill does not have a sufficient “off-ramp” that allows for taking a fentanyl-related substance off Schedule I if it is found to have a legitimate medical purpose.

Democrats control the Senate, which will take up the bill after House passage, and Mr. Biden can either sign or veto the legislation.

“Hopefully, a final compromise would look much more like what the Biden administration has put forward. It has more flexibility on mandatory minimums and includes an off-ramp,” Mr. Young said.

Likewise, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy said it gave Congress a plan in 2021 to “reduce the supply and availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyl-related substances, while safeguarding against racial disparities in prosecution and sentencing and reducing barriers to scientific research for all Schedule I substances.”

“We look forward to continuing to work with Congress to get this done,” the office said in a written statement.

Only two House Democrats, Reps. Angie Craig of Minnesota and Kim Schrier of Washington state, voted to advance the HALT Fentanyl Act at a committee markup in March.

Mr. Latta and his co-leader of the bill, Rep. H. Morgan Griffith of Virginia, have said the debate over mandatory minimums can be set aside for another day. They want to act on permanent scheduling now.

“This stuff is dangerous, the Lord willing the Democrats come around on this. To say we’re just going to let things go the way they are and handcuff our prosecutors out there so they can’t prosecute these cases, that’s a travesty,” Mr. Latta said. “I’ll be calling folks over [in] the Senate about it, see if I can get this bill out [of] there. We can’t keep doing short-term extensions. The DEA needs help.”

• Tom Howell Jr. can be reached at thowell@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.