SEOUL, South Korea — The leaders of South Korea and Japan took steps Thursday to repair frayed diplomatic and economic relations, but their high-profile Tokyo summit was held under a pair of shadows: the latest North Korean ballistic missile test and a lawsuit in South Korea that could scupper hopes of resetting bilateral ties.

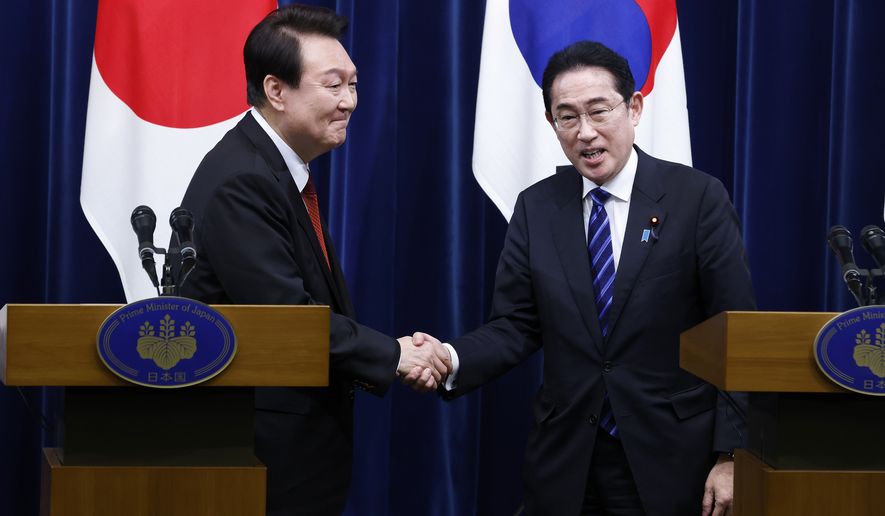

With strong encouragement from the Biden administration, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol embarked on a two-day state visit for talks with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida — the first by a Korean leader in 12 years. The leaders hope to repair ties between the two U.S. allies that deteriorated badly under Mr. Yoon’s predecessor, Moon Jae-in, who left office in 2022.

The summit produced some immediate progress. Mr. Yoon and Mr. Kishida agreed to resume regular leader visits and announced progress on settling a nasty trade dispute as they seek to overcome more than a century of antagonism and distrust.

“Korea and Japan share the same universal values of freedom, human rights and the rule of law, seeking common interests in security, the economy and the global agenda,” Mr. Yoon said at his meeting with Mr. Kishida, according to a message sent by his staff to foreign reporters. “The meeting … is the first step in overcoming the unfortunate history between the two countries and opening a new era of cooperation.”

The two leaders agreed to restore trade ties that were downgraded after a 2018 legal brouhaha over Japan’s use of wartime forced labor during its occupation of South Korea and to upgrade supply chain linkages via an “economic security dialogue.”

Japan is a key supplier of chemicals, machinery and components to South Korea’s semiconductor industry — the world’s largest supplier of memory chips. Since the Trump administration chose chips as a key weapon in its trade and technology offensive against China, they have become one of the world’s most strategic industrial components.

The two leaders also agreed to “completely normalize” a bilateral intelligence-sharing agreement, a key concern of Washington. The accord, suspended during the 2018 freeze in relations, is seen as critical for swiftly coordinating responses to North Korean provocations.

Seeking to underscore the positive atmosphere, the two men dined together with their wives in Tokyo. Mr. Yoon traveled with about a dozen South Korean business leaders who were set to meet their Japanese counterparts.

Japan and South Korea have separate bilateral alliances with the United States, but no trilateral security architecture links the three. That absence looks increasingly problematic for the U.S., making it hard to get on the same page with two critical East Asian allies in the face of the rising military power of North Korea and the expanding reach of China.

Just before the two leaders met in Tokyo, North Korea launched an intercontinental ballistic missile eastward from the Pyongyang area, South Korea’s military said. The ICBM appeared to be Pyongyang’s most advanced long-range missile, the Hwasong-17, which is capable of hitting the continental United States.

The launch compelled Mr. Yoon to chair a National Security Council meeting before departing for Japan. Japanese officials said they believed the ICBM splashed in the East Sea/Sea of Japan after an approximately 70-minute test flight.

Experts say North Korea has two reasons for the latest in a string of recent missile launches: to stress-test its arsenal to boost deterrence and to signal its displeasure over international political developments by garnering global attention.

Pyongyang has condemned not only the Tokyo summit but also the joint South Korean-U.S. Freedom Shield war games that kicked off Monday.

The launch was Pyongyang’s third test this week and its first ICBM test in a month.

Mr. Yoon on Thursday acknowledged that the divide between Seoul and Tokyo was not helpful given the threats both face in the region.

“The ever-escalating threat of North Korea’s nuclear missile program poses a huge threat to peace and stability not only in East Asia but also to the [broader] international community,” he said. “South Korea and Japan need to work closely together and in solidarity to wisely counter the threat.

“South Korea’s interests are not zero-sum with Japan’s interests,” he added, according to The Associated Press. Better bilateral relations would “greatly help both countries deal with their security crises.”

Seeking a deal

Mr. Yoon’s summit with Mr. Kishida is one of the rewards he earned immediately after revealing an initiative to end the 2018 dispute with Japan. On March 6, his government announced that South Korean firms would pay into a fund to compensate South Koreans forced to labor in Japanese industry at the end of World War II.

In 2018, the Supreme Court of Korea found Japanese companies liable to pay 15 laborers and seized the local assets of two firms, Nippon Steel and Mitsubishi Heavy, to provide compensation. The move infuriated Tokyo, which accused Seoul of bad faith and breaching international law.

Tokyo, already irked after the Moon administration unilaterally nixed a bilateral deal on “comfort women,” insisted that the issue had been resolved in a reparations package negotiated in 1965. That year, a bilateral treaty was accompanied by a Japanese financial package to South Korea worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Although it has won praise from President Biden and Mr. Kishida, Mr. Yoon’s initiative has not proved popular with many South Koreans. Some 60% disapprove of the deal, according to a Gallup poll.

The forced labor issue has not been laid to rest.

Three elderly victims have said they will not accept the money from the South Korean fund but will return to the courts. In a new development, two forced laborers filed a lawsuit against Mitsubishi.

All this means Seoul’s diplomatic ploy could yet founder on legal rocks.

“It will be hard to tell how the courts will rule,” said Shin Hee-seok, a legal expert at the Transitional Justice Working Group, a South Korean nongovernmental organization. “But the failure to persuade the victims, or to create a global compensation fund with contributions from the guilty Japanese businesses, may come back to haunt the bilateral relationship.”

• Andrew Salmon can be reached at asalmon@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.