Biden administration officials advertise clean energy tax credits and rebates that kick in this year as major savings for Americans struggling with inflation, but they fail to mention it will cost a whole lot of green to qualify.

Democrats’ tax-and-climate-spending law, dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act, sets aside $370 billion over the next decade to help Americans go green in an effort to fight climate change. Yet many households would need to spend hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to receive a fraction in tax savings.

Energy cost reductions primarily will benefit those with the means to make expensive home improvements or buy electric vehicles, even though the administration and Democratic lawmakers touted the legislation as a measure to cut high energy bills.

“Make saving on your energy bills a resolution for 2023, with the help of President Biden’s tax credits for energy-efficient upgrades,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in a post on Twitter.

“Starting right now, you can get tax credits to install more energy-efficient appliances for your house. Electric ovens, solar panels, heat pumps: you name it,” the president proclaimed on Jan. 1 on Twitter. “Save money while fighting climate change.”

The money is meant to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by helping Americans ditch gasoline-powered cars, electrify appliances and weatherize homes. Incentives are offered for installing rooftop solar panels, electric stoves, new windows, electric heat pumps and more.

Yet those projects are expensive. Households would have to spend multitudes on homes or electric vehicles to receive tax breaks. In addition, the benefits apply only to those who file taxes, which nearly half of Americans are not required to do.

“These programs disproportionately benefit the wealthy who can afford to shell out thousands of dollars at the front end to purchase expensive new appliances and retrofit their homes, but fail to actually save people money or reduce emissions,” said a spokesperson for House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Washington Republican.

Green energy advocates argue that the credits benefit renters indirectly because of incentives for energy-efficiency upgrades in apartments and commercial buildings.

Critics call it a government payout for the wealthy.

“Obviously, this is not necessarily your bread-and-butter, blue-collar worker who is going to be taking advantage of a lot of these credits,” said Preston Brashers, a senior tax policy analyst at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “For the bottom half or bottom third of Americans, those credits are completely unavailable. And for many others, a lot of people are living paycheck to paycheck. The idea of putting in a lot more money for weatherization or solar panels on your home … is a little bit out of reach for a lot of folks.”

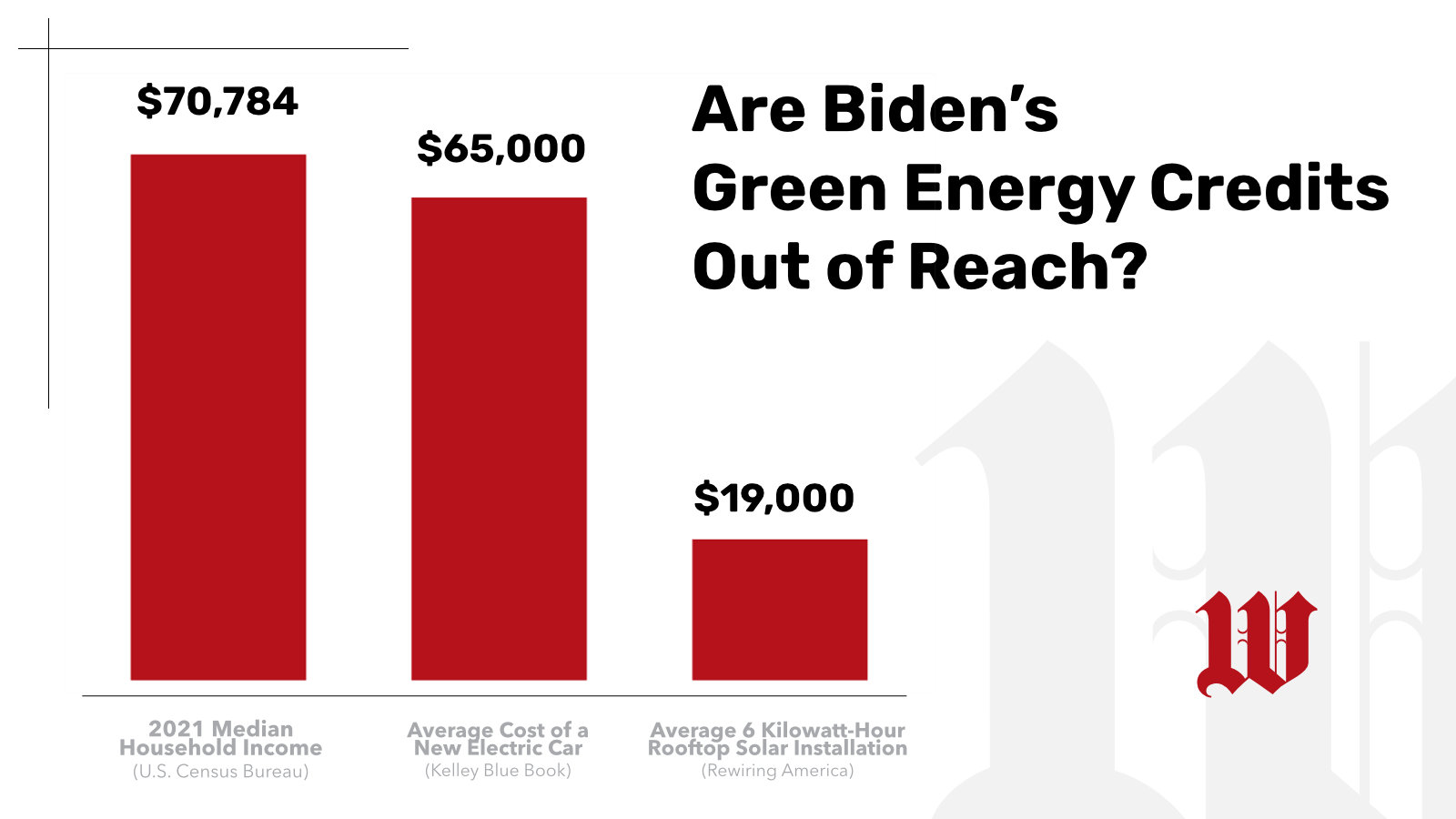

The average 6 kilowatt-hour rooftop solar installation runs about $19,000, according to the electrification advocacy group Rewiring America. A tax credit covering 30% of the costs would save $5,700, bringing the final price to $13,300.

Taxpayers also can obtain 30% tax credits on upgrades for energy-efficient heat pumps, windows, doors, electric panels and central air conditioners. These projects can cost several hundred to several thousand dollars.

Questions remain about how clean energy rebates will benefit low- and middle-income Americans as intended.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Some of the hypothetical scenarios the White House has used to tout benefits to lower- and middle-income individuals are dubious and unrealistic.

One example is a fictitious elementary school teacher named Suzy who makes $40,000 per year and is in the market for a new electric vehicle, the average price of which was $65,000 as of November, according to Kelley Blue Book. The cheapest new models are nearly $30,000. The White House said Suzy could receive up to a $7,500 credit.

With strict supply chain requirements for parts that electric vehicle manufacturers source and assemble in North America, the vast majority of new electric vehicles won’t qualify for the credits unless the auto industry makes a significant shift. Used electric vehicles costing less than $25,000 qualify for a credit of $4,000 or 30% of the sale price, whichever is less.

“Working families aren’t salivating for a tax break on $80,000 electric SUVs or expensive high-tech windows that they do not want and cannot afford,” Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming, the ranking Republican on the Senate Energy Committee, told The Washington Times. “They’re focused on being able to fill up their gas tanks and grocery carts in the same week. Americans need real relief now.”

Another White House example is a fictitious bank teller and a construction worker who are married with a combined annual income of $60,000. They want energy-efficient appliances in their newly purchased home. They are eligible for rebates that cover up to 100% of the costs, the White House said.

Clean energy rebates are meant to help low- and middle-income Americans by slashing the upfront costs rather than waiting for tax credits. Most of the credits, however, likely won’t be available until later this year. It’s also not clear exactly who will qualify.

States must establish their own rebate programs, including rules about who qualifies based on median incomes. Those earning less than 80% of their area’s median income could have most or even all of their costs covered. Those making 80% to 150% could have a portion covered.

The lower the income, however, the less likely it is that would-be beneficiaries own homes and qualify for rebates.

• Ramsey Touchberry can be reached at rtouchberry@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.