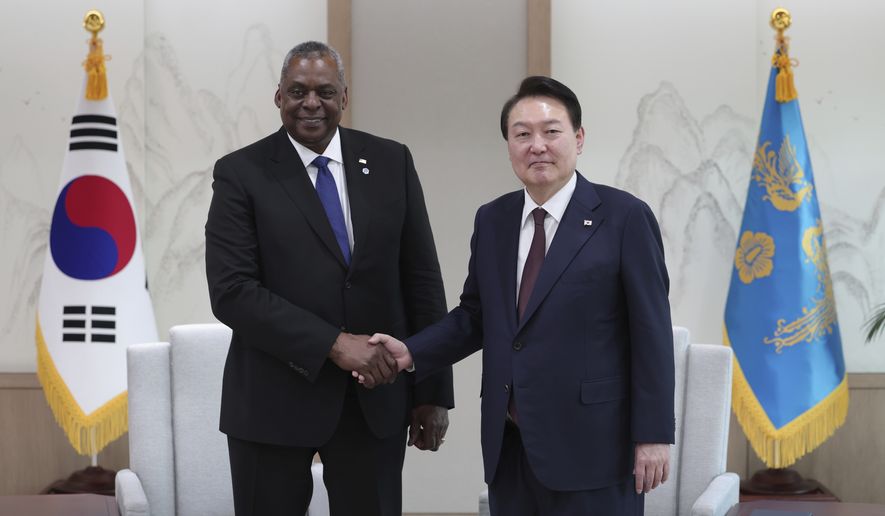

SEOUL — Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin on Tuesday reiterated America’s “iron-clad” commitment to South Korea’s defense but left two key issues for the alliance — one pressing, one long-term — unaddressed.

Mr. Austin, making his third trip to Seoul since becoming defense secretary in 2021, appeared set on steadying South Korean nerves over both the unprecedented pace of North Korean missile activities in 2022 and about the solidity of the Biden administration’s commitment as it also deals with crises in Ukraine, the Middle East and elsewhere.

Despite the good vibes at a joint press conference with his Korean counterpart, Mr. Austin and his hosts left much unsaid.

South Korean Minister of Defense Lee Jong-sup declined to say how Seoul would respond to U.S. and NATO entreaties to help arm Ukraine in its war with Russia. Mr. Austin ignored a question about the Pentagon’s stance on South Korea potentially seeking its own nuclear weapons. A similar silence reigned on tensions with China over the regional flash point of Taiwan.

As he made the visit, Mr. Austin penned a contribution for Seoul’s Yonhap News Agency on Tuesday, titled “The Alliance Stands Ready.” He repeatedly made clear in public comments that the U.S. “stands firm” in the alliance, which marks its 70th anniversary this year.

But a series of North Korean weapons tests in 2022 has generated fresh debate in South Korea over whether the U.S. would risk a North Korean nuclear strike on its own cities to assist its treaty ally in a crisis — and sparked talk of whether Seoul should pursue its own nuclear deterrent.

Washington’s commitment to Seoul remains “iron-clad,” Mr. Austin insisted. “That is not just a slogan, it is what we are all about.” The commitment, he added, encompasses “the full range of U.S. defensive capabilities, including conventional, nuclear and missile defense.”

The U.S. and South Korea have already agreed on an upgraded joint exercise schedule for 2023, a move that will almost certainly infuriate Pyongyang. Special interest is focused within South Korea on a joint tabletop exercise to be held in the U.S. in February, which will reportedly explore nuclear war contingencies.

Mr. Lee said Tuesday that the two allies had agreed on “information-sharing, joint planning and execution, and consultation mechanisms” regarding extended deterrence. He noted that last year’s deployment of American strategic assets to the peninsula amid tensions “was the embodiment of extended deterrence in action.”

But the two defense ministers danced around hard questions over responding to the mounting North Korean campaign, just weeks after South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol told reporters the allies were discussing for the first time “joint nuclear exercises.”

That led to a rare direct contradiction by a U.S. president as Mr. Biden said that was not the case, causing some embarrassment in Seoul.

Days later, Mr. Yoon caused another stir by raising the possibility of South Korea acquiring nuclear arms if North Korea continues escalating, instead of relying solely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella for defense.

The issue has been quietly discussed for years and was the centerpiece of a major conference held last year in Seoul.

But asked what about the U.S. stance on South Korea acquiring such weapons, Mr. Austin pointedly declined to respond.

Mr. Lee was barely more forthcoming when asked whether South Korea’s increasingly potent defense industry would help arm Ukraine. That initiative was urged Monday by visiting NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, though it would contravene Korean trade policy, which is against arming belligerents.

“I would like to leave my answer as, ‘We are directing close attention to the situation in Ukraine,’” Mr. Lee said.

Analysts said there was a need for both discretion and assurance on both sides.

“These are very difficult and sensitive questions,” said Daniel Pinkston, who studies international relations at Troy University. “High-level officials though they are, these kinds of decisions are above their pay grade.”

Go Myong-hyun, a research fellow at Seoul’s Asan Institute, said it was “interesting that Austin did not categorically reject the prospect of South Korea going nuclear, as he knows the optics of President Biden saying ‘no’ to the question of joint nuclear exercises — that did not go down too well. I think Austin understands that it is important to signal on a united front.”

Still given events like the Ukraine war, Mr. Biden’s 2021 pullout from Afghanistan and the fears of new weapons tests by Pyongyang, “I understand why the South Koreans are nervous,” Mr. Pinkston said. “And there is something about face-to-face meetings which builds trust, it is saying, ‘We have your back,’” Mr. Pinkston said.

But he added: “The two countries have different global interests: One is a major power, one is a middle power.”

• Andrew Salmon can be reached at asalmon@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.