DENVER — Two decades after the 1999 Columbine High School massacre and two months after five people were killed at an LGBTQ nightclub in Colorado Springs, Colorado lawmakers are drafting a sweeping ban on semiautomatic firearms.

If passed, the ambitious legislation would make Colorado the 10th state in the nation to ban the sale and transfer of certain semiautomatic guns while grandfathering in the state’s existing ones. California passed its ban in 1989, and most recently, Illinois’ ban was signed into law two weeks ago.

While Democrats hold large majorities in both chambers of Colorado’s Legislature, the bill faces uncertain prospects.

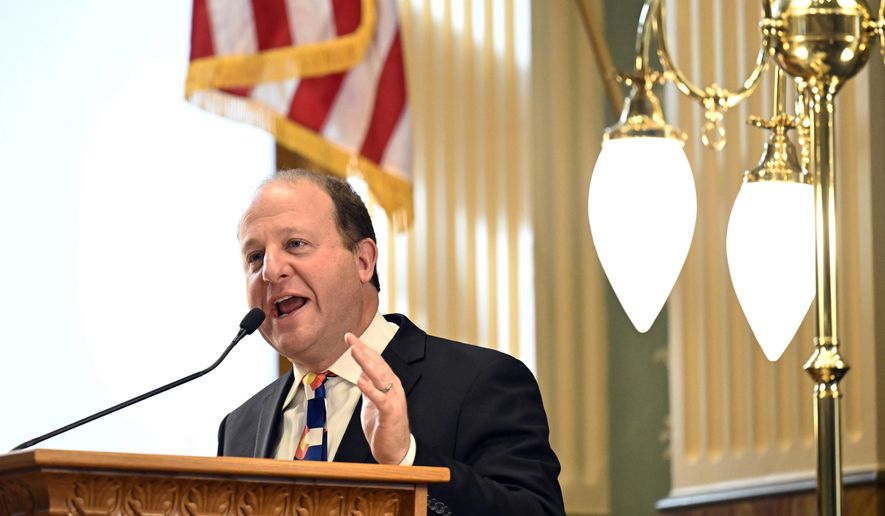

The draft legislation has already sparked conservative backlash and lawsuit preparation from the local branch of the National Rifle Association. While some Democratic leaders have given it tentative support, others have refrained from taking a stance - along with Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, who’s been noncommittal when questioned about the bill. It has yet to get a hearing in Colorado’s statehouse, which kicked off its session earlier this month.

One of the bill’s sponsors, Democrat Rep. Andrew Boesenecker, said there remains a long runway before the legislation’s introduction, with more stakeholder input to hear and potential concerns to accommodate. Boesenecker remains confident in its support, adding, “I always count my votes.”

To Boesenecker, an Evangelical Lutheran pastor and former music teacher and who represents a district north of Denver that includes the city of Fort Collins, the bill’s details will take time, but the argument is simple.

“I drop off my kids at school,” he said, “I could no longer continue to live … not knowing what might happen to them between that time I dropped them off and was able to pick them up.”

His draft of the bill prohibits the sale, transfer, importation and manufacture of semiautomatic rifles with detachable magazines that also have one or more of a list of seven characteristics that include a pistol grip, flash suppressor, folding stock or threaded barrel. The ban would also extend to certain semiautomatic shotguns and handguns but allow some exemptions including for military personnel and police officers.

Colorado residents who already own semiautomatic weapons would be allowed to keep them. Rapid-fire trigger activators, devices that modify a firearm’s fire rate, however, are banned flat out by the bill.

Boesenecker argues that the bill would put space between someone’s motivation to commit a violent act and the ready availability of a weapon to carry it out. While a federal ban would stop people from merely crossing stateliness to acquire semiautomatic firearms, he said, “states really need to lead the way.”

Colorado’s history is pockmarked by some of the country’s worst mass shootings that have killed an estimated 88 people since 2013, according to the Gun Violence Archive, which includes all shootings where at least four people were killed or injured not including the attacker. In recent years, 10 people were killed at a supermarket in the college town of Boulder in 2021 and five people slain in the shooting at Club Q in Colorado Springs in November 2022.

Authorities said suspects in both shootings used semiautomatic rifles. While the suspect in Boulder, Ahmad Al Aliwi Alissa, purchased his gun legally, police have not revealed how suspect Anderson Lee Aldrich obtained the weapon used in Colorado Springs.

The concern over mass gun violence has been heightened after California was hit by three mass shootings in eight days that have rocked the state.

In Colorado, a state that has only recently become a Democrat stronghold and has a libertarian streak, Republicans argue the bill would not just throttle Second Amendment rights but outlaw an important tool.

“I think these are kind of a knee-jerk reactions,” said Rep. Michael Lynch, the Republican house minority leader who said he can’t see any version of the bill being palatable. “I don’t represent a bunch of crazy gun toting people, but its people that it’s more a part of their life.”

Lynch pointed to rifles being used to shoot coyotes that are attacking sheep, but more important, he said, is possessing a gun for criminal deterrence. The understanding that rural Colorado residents are likely armed might make criminals think twice before seeking an easy target in areas where the sheriff’s response takes half an hour, he argued.

“It’s not taking into consideration the rural parts of the state,” Lynch said. “Nobody in Denver thinks about that.”

Colorado Senate President Steve Fenberg, a Democrat, said he would vote for the legislation and that he thinks most Democrats would as well. He added that “it may not be the most effective public policy to save lives.”

“Most of the lives that are lost are not from a mass shooting event,” said Fenberg, who worried that the vast majority of gun violence victims - from suicide and street violence - are overlooked by placing sole attention on mass shootings and semiautomatic firearm bans.

“I think there are probably policies that could make sense to do before an assault weapon ban policy,” he said.

To Fenberg, solutions include a number of other draft bills such as raising the minimum purchase age of a shotgun or rifle from 18 to 21 and strengthening red flag laws that allow law enforcement to temporarily remove someone’s gun.

He said the semiautomatic weapons ban “might not even be enforceable, yet we are all going to be talking about it for 100 days.”

Concern over the legality of the ban comes from current lawsuits against local Colorado municipalities, including Boulder, that have passed similar firearm restrictions. Last year, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order preventing the town of Superior from enforcing its ban.

While eight other states have semiautomatic firearm bans - California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York - according to Giffords Law Center, Illinois’ ban that was just passed this month is facing legal challenges after a judge also issued a temporary restraining order.

Daniel Fenlason, executive director of the Colorado State Shooting Association, said his organization is gathering donations from supporters in anticipation of a court battle and is drawing on support from its parent organization, the National Rifle Association.

“This bill hits almost every type of gun owner,” said Fenlason, who said he hopes for pushback from more center-of-the-road Democrats and the governor. “I think that a lot of the leaders in the Democratic Party see that and don’t want to negatively affect hunters or single moms trying to protect their family.”

Colorado House Speaker Rep. Julie McCluskie, a Democrat, told reporters she doesn’t yet have a stance on the draft bill. Rep. Monica Duran, the Democratic house majority leader, said she also doesn’t yet hold a position, but added, “I may have some questions, to be honest with you.”

Polis, who has proclaimed his support for expanding red flag laws, has avoided questions about his stance on the semiautomatic firearm ban. The governor sponsored a federal semiautomatic gun ban as a congressman in 2018.

Asked about the proposal, Conor Cahill, spokesperson for Polis, again avoided taking a stance, saying only in a statement that the governor “looks forward to hearing about additional ideas from Democrats and Republicans on effectively reducing violent crime.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.