Florida won’t be alone if it adopts non-unanimous jury verdicts in death penalty cases, but it would be the biggest outlier of the outlying states on capital punishment, legal experts say.

Only three of the 27 states that have the death penalty do not require a unanimous verdict. In Missouri and Indiana, a judge can make the decision if a jury can’t reach unanimity. In Alabama, a 10-2 jury can hand down a death sentence. Seven states have imposed moratoriums on capital punishment.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, and state lawmakers moved to allow a death sentence if at least eight of the 12 jurors agree. The legislation was introduced in the wake of the 9-3 jury vote on the death penalty for the 2018 Parkland high school mass murderer.

“It’s probably a bad idea. It will tie things up in litigation,” John Blume, director at Cornell Law School’s Death Penalty Project, told The Washington Times. “It’s an outlier, and what it would allow really is sort of what you saw in non-unanimous sentencing. It would basically dilute or remove minority participation.”

Richard Dieter, interim executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said the high school shooting case isn’t a reason for the state to upend the entire standard.

“It’s a big deal sort of going back on something so fundamental as our jury system in the country. It’s not just changing from 9-3 to 10-2. That might not be a big deal. But doing away with unanimity, I think, a lot of caution should be practiced in that change,” Mr. Dieter said. “And in the sense that this is happening in response to one case is a concern.”

A 2020 analysis from his group found that judge-imposed death sentences without jury unanimity “create a heightened risk that an innocent person will be wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death.”

“Death sentences imposed by judges without the unanimous assent of jurors … often have been applied in an arbitrary, discriminatory and politicized manner. That they also appear to create a significantly heightened risk that innocent people will be sentenced to death should be an important additional consideration in deciding whether this outlier practice should be permitted to continue or should be abandoned,” Robert Dunham, the center’s executive director, said in the analysis.

The Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that the Sixth Amendment requires a unanimous jury to convict a defendant of a serious crime. The ruling in Ramos v. Louisiana eliminated the state’s requirement that only 10 of 12 jurors must agree to a guilty verdict.

In the separate sentencing phase of capital trials, states do not have set requirements for jury unanimity on the penalty.

Basing its ruling on Ring v. Arizona in 2002, the Supreme Court has said a jury must find that a defendant meets an aggravated standard for imposing a death sentence. The court ruled that a unanimous jury must find the aggravated circumstance beyond all reasonable doubt.

“After that, then in most places, the jury also decides whether the person will get the death penalty or not,” Mr. Blume said. “In every state but three, it has to be unanimous.”

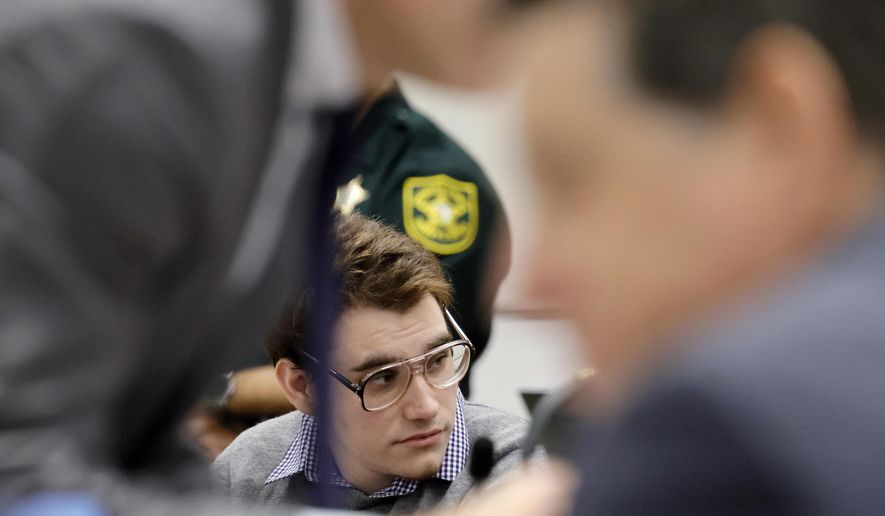

Late last year, a unanimous Florida jury convicted Nikolas Cruz of murdering 17 people and wounding 17 others at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018 but split 9-3 on imposing the death penalty. Cruz was sentenced to 34 consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole.

State officials have proposed non-unanimous juries in response to outrage from victims’ families.

Florida previously allowed a judge to hand down a death sentence if the majority of jurors agreed. After the U.S. Supreme Court tossed the state’s process, lawmakers in Florida proposed a 10-2 jury standard.

The state’s highest court, though, recommended that such sentences be unanimous. Since 2017, unanimity has been required in Florida’s death sentencing cases.

Robert Blecker, professor emeritus at New York Law School, said if a state doesn’t require a non-unanimous jury verdict, the ratio should be similar to what it takes to amend the U.S. Constitution: requiring a three-fourths vote of state legislatures, generally a “consensus.”

During the jury qualification process, when jurors are asked to swear that they could give a death sentence in an appropriate circumstance, some might say yes, but to them only someone like Adolf Hitler would meet their standard for execution, Mr. Blecker said.

“In effect, they are abolitionists,” he said. “The jury is supposed to represent the conscience of the community.”

• This article is based in part on wire service reports.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly reported the ratio on a jury vote supported by Robert Blecker.

• Alex Swoyer can be reached at aswoyer@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.