SEOUL — Russia’s cyberoffensive against Ukraine has proved unprepared, uncoordinated and unable to overcome a well-prepared, flexible series of Ukrainian defenses that have relied on experience and expertise and confounded prewar predictions. Kyiv has been widely assisted by overseas information technology partners from the public and private sectors, and its ability to call on a dense network of civilian specialists has provided critical civilian-military coordination in cyberwarfare, experts said.

Cyberwarfare was a leading topic of conversation at a major conference on state-sponsored threats in cyberspace in the South Korean capital.

The expectation of a swift collapse of Kyiv after its invasion last February was a key reason for the failure of Russia’s cyberstrategy so far, analysts said. The Russian invasion plan, drawn up by a small staff and only belatedly disseminated across the Russian military branches, left insufficient time for coordination of the online fight with the other facets of the offensive.

“They were not prepared, and they were not integrated with the rest of the Russian armed forces,” said a source who works for a NATO government, speaking on background about the Kremlin’s cyberwarfare assets.

“If you are a cyberintelligence operation and you have access to a communications system, you don’t want to destroy that communications system,” the source said. “But if you are not integrated with other forces, well — we saw evidence of that.”

Russia failed to deliver a knockout blow with its first wave of cyberattacks and used up its hacking tools early in the fighting.

SEE ALSO: Google wages war with Russians on digital battlefield

“We saw a lot of malware, but it was a limited arsenal and it takes time to rebuild that capacity,” the source said. “They used it up in the first few weeks and exposed it.”

The Russian online operatives’ inability to short-circuit Ukraine’s command, control and communications networks mirrored the struggles of Moscow’s conventional units in the invasion’s early days and weeks. Although Russia’s mass tactical artillery has caused significant damage, other arms of its war machine have been found wanting.

A daring assault by airborne shock troops in the war’s early hours lacked backup to secure targeted sites and proved catastrophic. Russian armor, uncoordinated and advancing along the predictable axes of Ukraine’s road network, were badly mauled as they stalled on open ground.

Russia’s once-vaunted Black Sea fleet lost its flagship, and its surface vessels have been unable to launch or sustain landings from sea. Russia’s air force has been unable to win aerial dominance, and even its missile and drone offensive is being countered.

Russian incompetence is just one side of the coin, conference attendees said. Ukraine’s forces have displayed unexpected competence, enlisting non-state and non-national actors to carry out unconventional strategies that have repeatedly taken the enemy by surprise.

A resilient defense

The experience of having battled Russia in the Donbas and over the annexed Crimea Peninsula for eight years before the war — and the links to Western militaries forged since 2014 — are seen as critical to Kyiv’s successful defense to date.

“A number of us had been supporting the Ukrainians in advance of the Russian invasion, building up defensive capabilities since 2014 with bilateral and multilateral support,” said Will Middleton, cyber director at the United Kingdom’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

In addition to British and U.S. support, NATO offered a training package in 2016 on command, control and communications and the European Union provided a rapid-response team in the months before the conflict, Mr. Middleton said.

“It is clear that [Ukraine’s] experience and expertise was thorough,” said Joe Murphy, deputy head of the British Foreign Office’s Cyber Policy Department Threats Team. “Every aspect of their resilience has been tested to the limit.”

Western arms aid — including anti-tank missiles, long-range artillery and heavy armor — was provided openly, but cyberintelligence support has been much more low-key.

“After the invasion, [Britain] shifted from long-term capacity building into direct support to give the Ukrainian defenders the tools, technology and equipment to better defend themselves,” Mr. Middleton said.

The U.S. offered “Hunt Forward” services to Ukraine in the months before the war that helped identify and build defenses against Russian malware and tradecraft and shared what was found with a commercial provider.

Ukraine also adopted some unconventional tactics to defend its IT and communications links. In the immediate aftermath of the Russian assault, government organizations uploaded all data to the cloud. Most governments hold national data in sovereign server farms, but Kyiv’s response put its data beyond the reach of Russian hackers.

“That was critical to their defense,” Mr. Middleton said. “It is very unusual for a sovereign state to put data somewhere else.”

Ukraine also opened its networks in real time, allowing international partners to identify threats and assist faster.

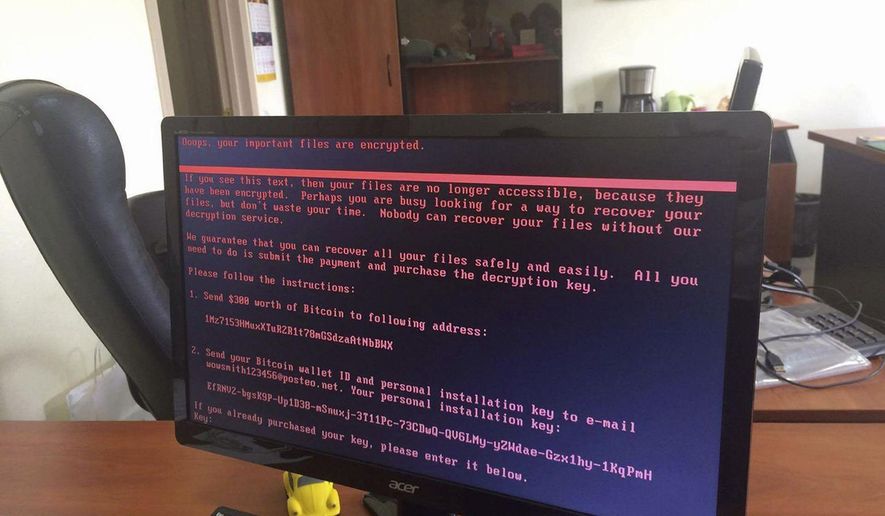

Rob Joyce, cybersecurity director at the National Security Agency, told The Washington Times recently that his agency leveraged a “power collaboration” with cybersecurity and information technology service providers to identify and eradicate malicious cyberoperations with large impacts in Ukraine. Such partnerships formed in the aftermath of devastating breaches across the U.S. in 2021, when cybercriminal gangs deployed ransomware against computer networks to extort payments from victims.

Private-sector outreach was central.

“Ukraine reached out to the private sector and moved incredibly fast to work hand-in-hand with it,” said Mr. Middleton, referring to U.S. tech companies such as Microsoft, Google and Starlink. “They were critical in helping Ukraine adjust. … They shared intelligence with Ukraine, patched problems and neutralized attacks.”

Ukrainians working for overseas IT firms enabled this strategy.

“What we saw in the early days of the response was private-sector companies being drawn in, using Ukrainian employees in the EU, the U.K. and the U.S.,” Mr. Middleton said. Those employees “drove companies to engage and provided insights into Ukrainian systems.”

Google said this week that it saw cyberattackers on the digital battlefield in Ukraine that the NSA warned about hitting U.S. infrastructure in 2021.

The search engine giant disclosed the links in a report called “Fog of War,” which said the Ukrainian government is under “near-constant digital attack” from hackers overseen by the GRU, the Russian military intelligence service.

“We’ve observed a notable uptick in the intensity and frequency of Russian cyber operations designed to maximize access to victim networks, systems and data to achieve multiple strategic objectives,” the report said. “For example, GRU-sponsored actors have used their access to steal sensitive information and release it to the public to further a narrative, or use that same access to conduct destructive cyberattacks or information operations campaigns.”

Pre-invasion Ukraine was a key IT outsourcing destination for EU companies. Post-invasion, a deep talent pool of IT-savvy, English-speaking volunteers was at Kyiv’s disposal.

Android apps guide artillery on the battlefield while public relations campaigns enlist global sympathies and support on social media. These private-public partnerships provide key learning for future combatants.

It ain’t over till …

Russia should not be counted out, analysts at the conference warned.

“A number of commentators have said we have not seen ‘Cybergeddon’ in Ukraine,” Mr. Middleton said. “But we are seeing cyberspace fiercely targeted and contested on a daily basis, with the Russians launching attacks against Ukraine’s communications and critical national infrastructure.”

The NATO country source noted that Moscow’s forces are jamming Ukrainian signals and effectively synchronizing human and electronic intelligence.

Indeed, Soviet and Russian armies have a history of suffering early-stage humiliations, integrating hard-won learnings and then ending conflicts with victories, including the ultimate victory over the Nazis in World War II and the string of Chechen wars on Russian soil in the 1990s and 2000s.

“Don’t underestimate the GRU and the FSB,” the source said of Russia’s military intelligence directorate and its state security bureau. “They are highly capable.”

• Ryan Lovelace contributed to this report.

• Andrew Salmon can be reached at asalmon@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.