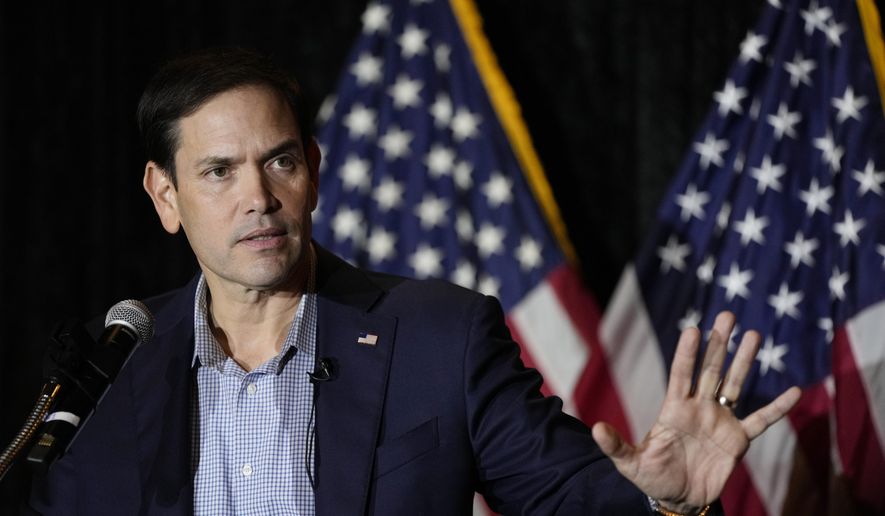

Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida says anyone who causes someone’s death by distributing fentanyl should face felony murder charges requiring a minimum term of life in prison.

It is the latest idea in a Washington scramble to rein in the steady stream of deadly synthetic opioids that Mexican cartels are sending across the border.

Other lawmakers want to authorize military force against the cartels, saying they should be placed on the same footing as the Islamic State or Osama bin Laden. Still others are prodding the State Department to reengage with China to disrupt the flow of fentanyl ingredients from Asia to clandestine labs in Mexico.

The real-world impact of the Rubio bill would be to treat fentanyl distribution resulting in death as first-degree premeditated murder that can result in a life sentence.

Right now, his office said, cases are governed by the Controlled Substances Act and terms may vary, though they are less severe than what the Rubio legislation would require.

A South Florida fentanyl dealer, for instance, received a 20-year term in federal prison last summer after police determined he drove another man to a hotel and gave him four fentanyl capsules. The other man was found dead the next morning.

“We need to stop the flow of fentanyl and punish those responsible for poisoning our communities. If the illicit sale of this drug results in death, then the seller should be charged with felony murder. That is a simple, common sense step we can take right now to help turn the tide and protect our communities,” said Mr. Rubio, a Republican, in a news release.

Overdose deaths involving a synthetic opioid have soared from nearly 10,000 in 2015 and 20,000 in 2016 — the period when fentanyl started to infiltrate the U.S. drug supply — to 56,000 in 2020 and more than 70,000 in 2021, according to the most recent federal figures available based on death certificates.

The annual rate of fatal drug overdoses of any kind peaked at 110,000 for the 12 months preceding March 2022, before declining for five months in a row. Lawmakers opened the new Congress by pressuring the Biden administration to address the unrelenting flow of fentanyl — often in counterfeit pills — across the border.

Reps. Dan Crenshaw, Texas Republican, and Mike Waltz, Florida Republican, introduced a bill that would create an authorization for use of military force to target the Jalisco and Sinaloa Mexican drug cartels.

“We cannot allow heavily armed and deadly cartels to destabilize Mexico and import people and drugs into the United States. We must start treating them like ISIS — because that is who they are,” Mr. Crenshaw said.

The type of force would be up to the president and executive branch to decide, though it could include special operations on high-value targets near the border or cyber operations against the cartels. Sponsors hope a military force authorization might compel the Mexican government to take a bigger role in fighting the cartels.

Lawmakers are also concerned about nations that continue to feed the cartels fentanyl ingredients.

Sen. Chris Murphy, Connecticut Democrat, on Thursday urged the State Department to engage with China, which stopped shipping fentanyl directly to the U.S. under pressure from the Trump administration in 2019 but continues to ship fentanyl-precursor chemicals to Mexico.

Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman told the senator that Secretary of State Antony Blinken will raise the issue “when he does get back to meeting in Beijing, which we will do when we think conditions are right.”

Mr. Blinken’s planned trip was scrapped due to a confrontation over the Chinese spy balloon that was discovered over the continental U.S.

Ms. Sherman said the U.S. would like Mexico to exert pressure on China and other countries to stop sending chemicals that cartels can turn into fentanyl.

“This is a really terrible problem. We are taking a laser focus on organizing an international effort to stop this,” she said.

President Biden raised the fentanyl issue with Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador at a recent summit of North American leaders in Mexico City.

Mr. Lopez Obrador said he put the Mexican navy’s secretariat in charge of ports and customs to try to deal with the problem.

The White House is pursuing a two-track strategy of increasing treatment for substance use disorder and cracking down on drug trafficking. It recently eliminated a burdensome federal requirement, known as the “X waiver,” so that more doctors can prescribe drugs such as buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder.

Mr. Rubio pushed his get-tough bill a few days after Mr. Biden called on Congress to “stiffen penalties” for fentanyl traffickers.

Mr. Biden was referring to an effort to permanently schedule fentanyl-related substances as a class on Schedule I to prolong harsh penalties for traffickers. Temporary scheduling of the substances will expire in December 2024.

Experts say temporary efforts to place fentanyl on Schedule I — the group of drugs with the highest risk of abuse — resulted in fewer fentanyl analogs because bad guys were no longer able to tweak compounds in their drug supply to get around specific bans written in the law. It also made things easier for law enforcement.

“It makes it easier to prosecute because otherwise, they have to get [the substance] tested, they just have to go through more hoops,” said Regina LaBelle, who served as acting director in the Office of National Drug Control Policy during Mr. Biden’s first year in office.

Lawmakers want to make that scheduling authority permanent, saying it would result in stiffer penalties under guidelines from the U.S. Sentencing Commission and send a signal to China and other governments that the U.S. is serious about tackling the problem.

A White House plan, however, says fentanyl-related substances should be exempted from mandatory minimum criminal penalties when an offense is based on the quantity of a drug an offender had.

Minimums would still apply in cases where drugs resulted in bodily injury or death, yet the administration says judges need flexibility in other cases. Also, advocates on the left are pressuring Mr. Biden to treat drug addiction as a medical problem instead of using criminal penalties that may simply push users into other dangerous drugs.

House Republicans say eliminating the mandatory minimums would undermine the point of putting the drugs on Schedule I, so lawmakers must find a way through the impasse.

“There’s going to be big pressure on both sides. You’ve got to do something on fentanyl,” said Ms. LaBelle, who is the director of the Addiction and Public Policy Initiative at the O’Neill Institute at the Georgetown Law Center.

She said whether Congress can settle its differences over permanent scheduling is difficult to predict, “given how long they’ve been debating this.”

“It’s easy to kick the can down the road,” she said.

• Tom Howell Jr. can be reached at thowell@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.