President Biden is threatening to share drug companies’ innovations with competitors if they don’t comply with his price caps.

Such an aggressive use of federal power may tackle high-priced prescription drugs that frustrate Americans, but critics warn that Mr. Biden could end up preventing the creation of advanced medications.

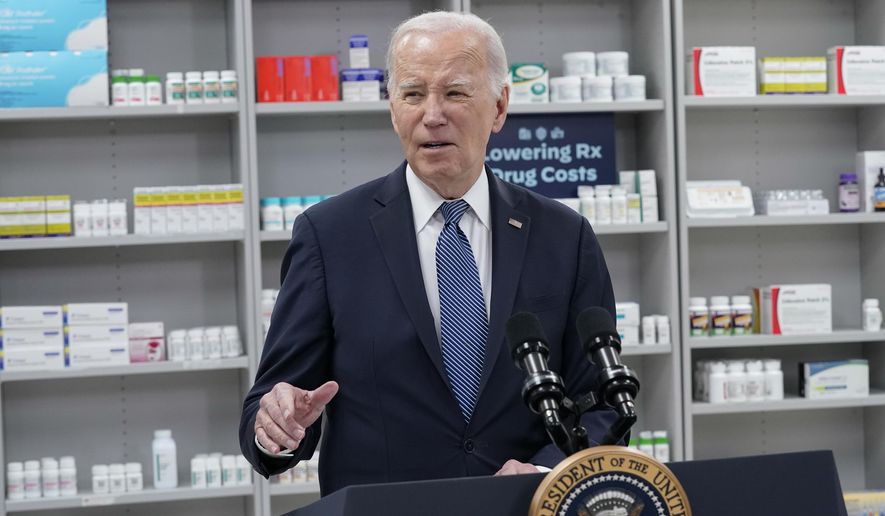

The administration announced that it would exert its right to revoke licenses for drugs it deems exorbitantly priced as Mr. Biden heads into an election year with sagging poll numbers.

Voters are souring on Mr. Biden partly because of skyrocketing prices at the gas pump, the grocery store and beyond.

More than 80% of American adults say the cost of prescription drugs is “unreasonable” and nearly 30% cannot afford to buy their prescription medication, a Kaiser Family Foundation poll has found.

Accusing pharmaceutical companies of outright price gouging, Mr. Biden said he is taking action.

The president is greenlighting a policy exercising the federal government’s “march-in rights” on some drug patents, handing them over to competitors if drugs produced by companies with the help of federal funding “are not made available to the public on reasonable terms, including based on price.”

The administration framed the move as a price-cutting initiative that wouldn’t change any laws but rather clarify provisions of the Bayh-Dole Act.

The 1980 law allows the government to seize a company’s patent if it does not make available to the public its products that taxpayer money helps develop.

Mr. Biden said the act was meant to include pricing.

“We’ll make it clear that when drug companies won’t sell taxpayer-funded drugs at reasonable prices, we will be prepared to allow other companies to provide those drugs for less,” White House National Economic Adviser Lael Brainard said on a press call.

Pharmaceutical companies and free market advocates immediately criticized the Biden administration’s interpretation of the Bayh-Dole Act. They said government use of pricing as a reason to seize patents would undermine intellectual property protections.

Such a move would chill investment and significantly reduce innovation and partnerships with the federal government, ultimately preventing lifesaving drugs from reaching the market, they said.

Drug companies have justified the high prices as the cost of research and development.

“It will stifle innovation because it introduces extensive uncertainty about whether your patents will remain exclusive to your product, your development, and your commercialization efforts over the years with private investment money,” James Edwards, executive director of Conservatives for Property Rights, told The Washington Times.

Jocelyn Ulrich, deputy vice president of policy and research for drug company lobbyist PhRMA, said the Bayh-Dole Act was never intended to target drug pricing as a justification for government seizure of patents.

The National Institutes of Health has declined all requests to use the Bayh-Dole Act to control drug prices, most recently for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine and the prostate cancer drug Xtandi.

“If the government were to advance a policy that would encourage the use of march-in for pricing, it would have significant detrimental effects on the ability of the private sector to collaborate with the government to research and develop additional treatments and cures for patients,” Ms. Ulrich said.

The Biden administration began considering the Bayh-Dole Act as a prescription drug price control tool in March after the NIH rejected a petition to hand over the patent for Xtandi to a competitor.

In clinical trials, prostate cancer patients who took Xtandi had a 61% lower chance of their cancer progressing compared with men who did not take the drug.

The yearly cost of Xtandi treatment, which was partly developed with grants from the Department of Defense and NIH, is as high as $180,000 per patient in the United States. That’s double or quadruple the prices charged to patients in other countries, including Canada.

The consumer groups Knowledge Ecology International and the Union for Affordable Cancer Treatment petitioned the NIH to make the patent available to Biolyse Pharma, which offered to sell a generic version of the drug for $3 per pill, a 95% markdown from the price that drugmakers Astellas and Pfizer charge for Xtandi.

After NIH declined the petition, the Health and Human Services and Commerce departments were directed to reconsider the Bayh-Dole Act as a tool to control drug pricing. Along the way, they stripped out a Trump-era draft rule that would have blocked agencies from considering product prices in determining whether it had the right to seize patents.

Consumer advocates argue that the government is justified and has not been aggressive enough in ensuring that drug companies charge reasonable prices after spending billions of taxpayer dollars on research and development.

“The problem is the funding agencies that have let the patent holders get away with murder and don’t use the march-in remedy for abuses of rights,” Knowledge Ecology International Director James Love, who petitioned the NIH on Xtandi, said after Mr. BIden’s announcement.

Dr. Joel Zinberg, a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute and director of the Paragon Health Institute’s Public Health and American Well-Being Initiative, said the high prices of some drugs reflect the cost of innovation and cheaper generic versions eventually reach the market without government intervention. Americans often pay higher prices but have earlier access to the drugs than patients in other countries and later pay less than in other countries for generics.

He cited American-made HIV and hepatitis C drugs that have decreased considerably in cost just a few years after their introduction.

“Within that initial time frame for some of these innovative drugs, the prices are higher here,” Dr. Zinberg said. “But on the back end, we’ve gotten the benefit of those innovative drugs at much lower prices.”

The government does not provide data on exactly how much it spends on drug development.

Derek Lowe, who writes about the pharmaceutical industry and spent decades developing drugs for schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, osteoporosis and other diseases, said he estimates that 15% of drugs come from universities and other academic institutions and are thus directly backed by some government funding.

For other drugs, government funding may be far more limited and harder to quantify, raising questions about which drug patents the Biden administration would truly have the right to seize and hand over to competitors.

“The question will be: What does it actually mean to be developed with federal funding? Does that mean if there was a drop of federal funding 25 years ago that has pretty much died the entire thing is tied to federal funding?” Mr. Lowe told The Times. “That would be a tough argument to make.”

The Biden administration is accepting public comments on a draft framework of the rule.

The matter is almost certain to end up in the courts.

More than half a dozen drug companies, PhRMA, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have sued the Biden administration to block a new law allowing the federal government to negotiate the prices of drugs it covers under Medicare beginning in 2026.

Consumer groups argue that the lawsuits are meritless. They point to companies jacking up prices on critical drugs such as Januvia, a Type 2 diabetes drug produced by Merck that would be part of the government’s price negotiations.

The drug has been on the U.S. market for 17 years. Medicare has spent $28 billion on the drug since 2010 and $4,343 per Medicare beneficiary in 2021, according to Protect Our Care, a consumer group. The company charges countries, including Australia, 87% less for Januvia.

Mr. Lowe said he suspects election-year politics played a role in Mr. Biden’s threat to drug companies. Mr. Lowe also acknowledged the companies have long been angering consumers with aggressive pricing of critical drugs.

“I’ve been saying for years that my own industry has been asking for trouble,” Mr. Lowe said. “And by golly, here it is.”

• Susan Ferrechio can be reached at sferrechio@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.