Under increasing pressure from environmental activists, President Biden took a dramatic step last month to usher in the use of electric heat pumps in homes, even though for most households, it would significantly raise heating costs.

Mr. Biden invoked the Defense Production Act to authorize spending $169 million to bolster electric heat pump manufacturing.

Mr. Biden and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm boasted the move would result in thousands of high-paying manufacturing jobs “while creating healthier indoor spaces through homegrown clean energy technologies.”

The Biden administration did not promise cheaper energy bills for everyone, because for most American households, installing heat pumps would raise costs substantially.

About 60% of homes used natural gas for heating spaces and water last year, according to the government’s Energy Information Administration.

The Department of Energy determined natural gas heat was more than three times cheaper than electric heat last year and according to the EIA, natural gas will remain one-third the cost of electric heat until at least 2050.

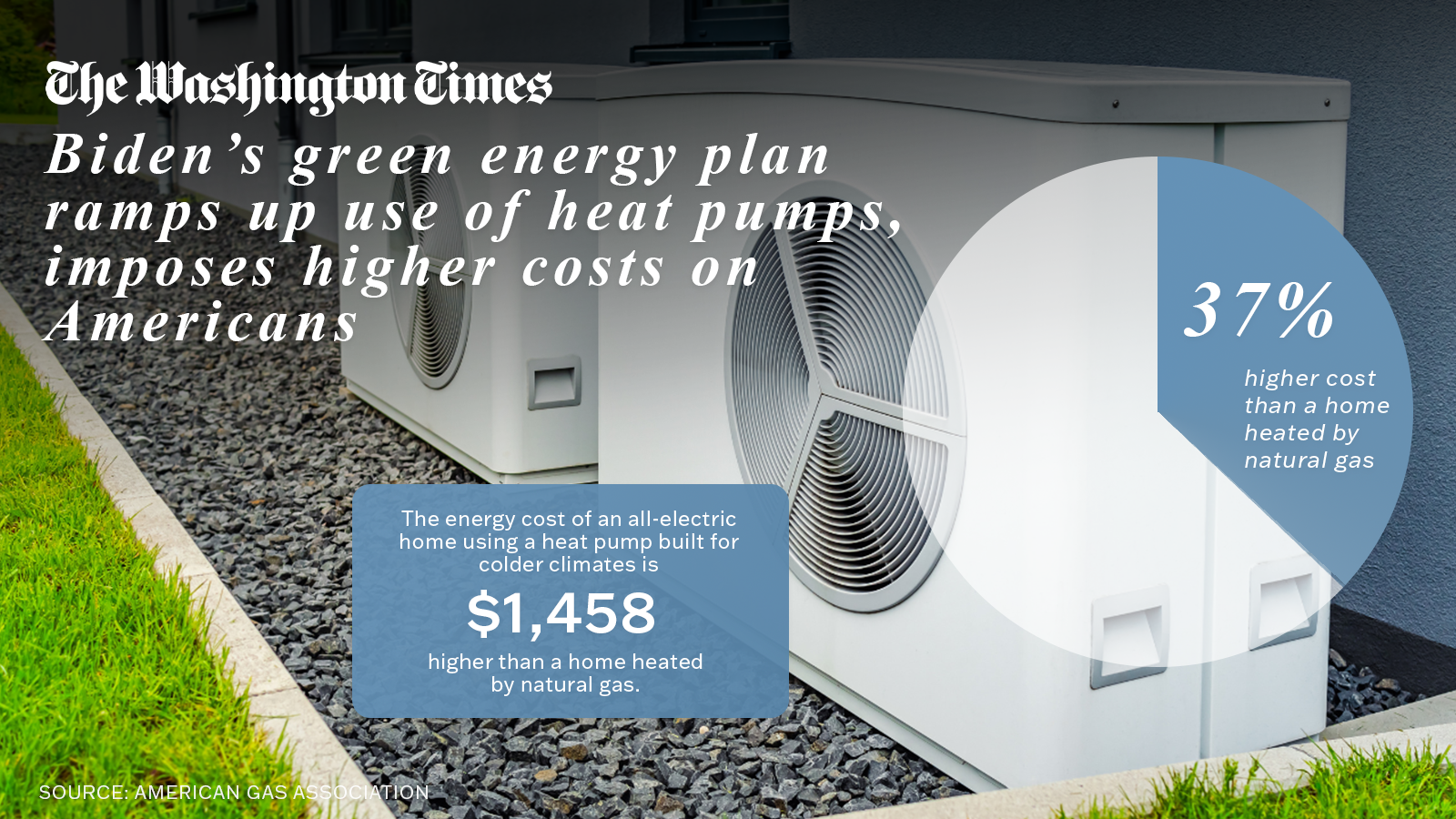

The American Gas Association’s own analysis found the energy cost of an all-electric home using a heat pump built for colder climates is $1,458 or 37% higher than a home heated by natural gas. The natural gas-heated home saves an average of $390 per year compared to a house that uses a cold-climate heat pump.

Heat pumps save money for those using propane or heating oil. About 5% of U.S. households use propane as their primary source of heating fuel and even fewer — 4.4% — use heating oil.

“The problem with heat pumps is that they make sense for some homeowners, but they don’t make sense for other homeowners,” said Ben Lieberman, a senior fellow who specializes in environmental policy at the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

American Gas Association President and CEO Karen Harbert said the association was “disappointed” by Mr. Biden’s use of the Defense Production Act to produce heat pumps, arguing it unfairly undermines natural gas, which she said is responsible for 60% of the electrical grid’s reduction in carbon dioxide emissions.

“We are deeply disappointed to see the Defense Production Act, which is intended as a vital tool for advancing national security against serious outside threats, being used as an instrument to advance a policy agenda contradictory to our nation’s strong energy position,” Ms. Harbert said.

The Defense Production Act became law in 1950 as part of an effort to bolster national defense at the start of the Korean War.

It’s been broadened over the years and has been increasingly used for purposes well beyond the traditional scope of national defense.

President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act in 2020 to ramp up the production of ventilators and other equipment needed to address the COVID-19 pandemic and later to mandate beef, poultry and egg plants remain open amid pandemic shortages.

Mr. Biden has invoked the act several times during his presidency to provide equipment to fight wildfires, to produce parts for submarines and to expand the production of baby formula.

Mr. Biden invoked the act on Nov. 17 to fund heat pump production “on the basis of climate change,” the administration announced.

“Today’s Defense Production Act funds for heat pump manufacturing show that President Biden is treating climate change as the crisis it is,” said John Podesta, Mr. Biden’s climate czar.

Environmental groups are promoting heat pumps to speed up the elimination of all fossil fuel use in homes and buildings and their efforts dovetail with Biden administration policies that aim to eliminate fossil fuels, including natural gas, from the nation’s electrical grid by 2035.

“The advanced state of heat pump technology coupled with decarbonization of the electrical grid makes heating with residential heat pumps a valuable tool for climate action for nearly every state today,” Lacey Tan and Jack Teener wrote in an analysis released by the Rocky Mountain Institute, an anti-fossil fuels group.

The institute predicts the replacement of gas furnaces with heat pumps could reduce “climate pollution” from home heating by up to 93%. It calculated the use of gas or fuel oil for heating, hot water and cooking made up more than 10% of U.S. carbon emissions in 2021.

The institute has pushed to eliminate gas stoves and was criticized last year after releasing a largely debunked report claiming gas stoves cause asthma in children.

For those who use heating oil or propane, electric heat pumps can save money. Newer technology has made heating pumps far more functional even in some of the nation’s coldest climates, although most far-northern households with heating pumps also have a backup system that uses heating oil or natural gas.

According to the EIA’s winter fuels outlook, heating the average home with propane from November through March this year will cost $1,337, compared to $1,063 for electric heating.

The EIA predicted heating oil would cost $1,856 during the same period. Natural gas heating came in the lowest, at $605.

Heat pumps, however, come with higher installation and maintenance costs compared to heating oil and natural gas.

The cost of installing a heat pump ranges from an average of $8,000 to up to $16,000 depending on the size of the house and the type of heat pump system. New federal tax incentives that take effect in 2024 will provide rebates of up to $8,000 to install new heat pump systems.

Several states have already ramped up rebate programs to help install heat pumps in homes, among them Maine and Vermont, where many households use expensive propane and heating oil.

More than 150,000 heat pumps have been installed in Maine homes using federal and state rebates, said Michael Stoddard, executive director at Efficiency Maine Trust, an agency that works to lower energy costs and cut carbon emissions.

Maine consumers have been willing to install heat pumps because new technology has improved their performance in colder climates and they are a cheaper heating source than the fuels most homes in the state use, he said.

Oil is the main source of heating fuel in 80% of Maine homes, according to the University of Maine.

“Heating our homes and businesses is a major preoccupation for everybody and we are sensitive to the costs,” Mr. Stoddard told The Washington Times. “So when some new technology comes along that can do that job better, and cheaper, everybody takes notice.”

The state also helped ramp up the number of Maine businesses that could distribute and install the heat pumps, creating jobs and shortening wait times.

Mr. Stoddard said he believes nearly 20% of existing Maine homes and one-third of newly constructed homes now have heat pumps.

“And that’s growing by the month,” Mr. Stoddard said. “It’s really taking off.”

But fossil fuels continue to play a critical role in homes with heat pumps.

Most Maine residents with heat pumps have oil or gas backup heating systems that kick in if the temperatures drop below zero, Mr. Stoddard said, and some homeowner insurance companies will not insure homes that use only a heat pump.

Maine’s consumer rebates for heat pumps are mostly funded by a regional carbon tax on power plants in 11 Eastern states.

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, is set to remove his state from the group at the end of the year because the cost of the tax is passed down to individual ratepayers at a cost of about $25 per year.

Consumers who use natural gas may eventually be forced to convert to electric heat pumps in states and municipalities that have committed to ending the use of fossil fuels.

In May, New York became the first state in the country to ban natural gas in new residential buildings beginning in 2026.

Democratic-run cities across the U.S. are mulling similar bans or have imposed them already, but not always successfully.

A federal appeals court in April threw out a Berkeley, California, ban on natural gas hookups in new construction, ruling the city overstepped its authority.

A version of this story appeared in the On Background newsletter from The Washington Times. Click here to receive On Background delivered directly to your inbox each Friday.

• Susan Ferrechio can be reached at sferrechio@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.