Part 1 of 3

Lindsey Ash says she likely would have sought a liberal arts degree in speech therapy — until a high school class steered her toward science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do in high school and had resigned myself to going into college with a random major and probably changing it five different times,” said Ms. Ash, who attended Kentucky’s private Christian Academy of Louisville. “I took a design-thinking class right before senior year and learned that you can have a career in creativity and absolutely fell in love.”

Now a senior majoring in industrial and innovative design at Baptist-run Cedarville University, the 22-year-old can’t imagine doing anything else as she prepares to graduate and pursue an industrial design career.

Ms. Ash, who wants to design scientific products and spaces for hospitals and schools, is among the droves of students who have abandoned the liberal arts for STEM majors.

The abundance of STEM-related scholarships and high-paying STEM jobs have contributed to years of struggle to attract students to the humanities. Potential historians, English teachers, art researchers and sociologists are opting instead to enter programs for careers in data systems analysis, information security, mechanical engineering and aerospace engineering.

Although no government agency tracks liberal arts enrollment as distinct from other programs, officials in higher education say the pandemic shutdowns accelerated the trend by decreasing interest in humanities majors. Colleges and universities nationwide have cut humanities programs, and several liberal arts schools have closed in recent years.

Last week, trustees announced that private Iowa Wesleyan University will close at the end of this semester because of rising costs, shifting enrollment trends, reduced fundraising and the refusal of Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican, to give the 181-year-old school another $12 million in COVID-19 relief funds.

In February, trustees at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia, voted unanimously to cut nine undergraduate majors and one graduate degree in the liberal arts. They noted that those programs had graduated only a handful of students in the past decade. The private Catholic campus enrolls 2,606 undergraduate students and charges $35,950 a year for tuition.

Marymount is ending its bachelor’s degrees in art, economics, English, history, philosophy, secondary education, mathematics, sociology and theology, as well as its master’s degree in English and humanities. Mathematical topics such as logic, algebra and geometry have long been parts of liberal arts education. Studies such as advanced calculus, linear algebra and statistical analysis have come to be regarded as STEM topics.

SPECIAL COVERAGE: Oh, the humanities! The death of liberal arts in higher education

“I am appalled that Marymount’s board of trustees has voted to eliminate these programs, and I certainly see this as part of the larger erosion of the liberal arts across the country,” Ariane Economos, a philosophy professor who directs Marymount’s School of the Humanities and Liberal Arts Core, told The Washington Times.

“Increasingly, we are seeing university administrations who seem to believe that the role of the university is to provide students with vocational training only,” Ms. Economos said. “It’s also shocking that Marymount has begun advertising itself as STEM-centered and yet has decided to eliminate its math program as part of these cuts.”

Developed as the centerpiece of secular higher education in Europe during the Middle Ages, the traditional liberal arts covered seven subjects: the “trivium” of grammar, logic and rhetoric alongside the “quadrivium” of geometry, arithmetic, astronomy and music.

Students aspiring to law school and medical school continue to major in speech, political science, chemistry and biology.

Advocates have long argued that the liberal arts serve as “finishing school” for careers that require graduate degrees, such as business, law and medicine. A liberal arts education not only nourishes the soul but also develops the habits of thinking deeply, writing coherently, speaking clearly, listening carefully and making sound judgments — qualities that they say employers value.

The value of “knowledge for its own sake,” as ancient Greeks understood a classical education, lies in having surgeons who know ethics, defense lawyers who have mastered public speaking and politicians well-versed in history and political science.

SEE ALSO: Colleges close books on traditional subjects as students pursue paths to higher salaries

‘On the decline’

According to an analysis of federal data by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 861 institutions ceased operating from 2004 to 2021. Most were small liberal arts schools, often founded in the 19th century as Christian women’s colleges that had struggled for years with dwindling enrollments after the expansion of coeducation.

Green Mountain College, a secular private school in Vermont, cited insufficient funds when it closed in 2019. Its “progressive program” specialized in environmental liberal arts.

Three cash-strapped private liberal arts colleges in the San Francisco Bay Area have moved to close their programs or campuses. In Oakland, Holy Names University said it would close its Catholic campus at the end of this semester and Mills College, a women’s school, merged last year into private Northeastern University. Notre Dame de Namur University in Belmont, a Catholic school, has announced that it will end all undergraduate programs and offer only graduate school classes.

Public universities have increasingly ended humanities courses as part of core requirements for undergraduates.

A 2020 survey from the American Council of Trustees and Alumni found that just 32% of all colleges and universities required students pursuing bachelor’s degrees to take a literature class. Only 12% had an intermediate foreign language requirement, 58% mandated a general mathematics course and 18% required a survey course in U.S. government or history.

In ACTA’s 2022-2023 survey, those numbers dropped to 27% for literature, 11% for a foreign language, 57% for math and 19% for U.S. history.

Nonetheless, many liberal arts majors continue to report high satisfaction levels. Programs featuring great books — the tomes from antiquity to the present that are widely regarded as the epitome of Western civilization — have touted the benefits of primary source literature for producing well-rounded graduates.

“My college experience has been wonderful thus far,” said Ellie Richards, a sophomore majoring in English and philosophy at the University of Dallas, a Catholic school. “I’ve spent hours in dynamic conversation over Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy,’ Aristotle’s ‘Nicomachean Ethics’ and Evelyn Waugh’s ‘Brideshead Revisited’ with peers from all different majors.”

She said she is not concerned about entering the workforce after graduation.

“My primary concern is to be a well-formed human being and to learn to write, read, converse and think well,” Ms. Richards said. “I hope to be a mom one day and to develop the virtues required to be a good wife and mom. If I were to enter into the workforce, I would love to work at The Heritage Foundation eventually after maybe doing a master’s degree.”

Inflation has pressured a growing number of Ms. Richards’ peers to compare the benefits of the liberal arts with the rising costs of a four-year degree.

Cedarville University, based in Columbus, Ohio, is the only private Christian school offering a bachelor’s degree in industrial and innovative design. Officials there say graduates from the program earn average starting salaries of $65,000 to $77,000 a year as engineers and designers at companies such as Honda, Nike and New Balance.

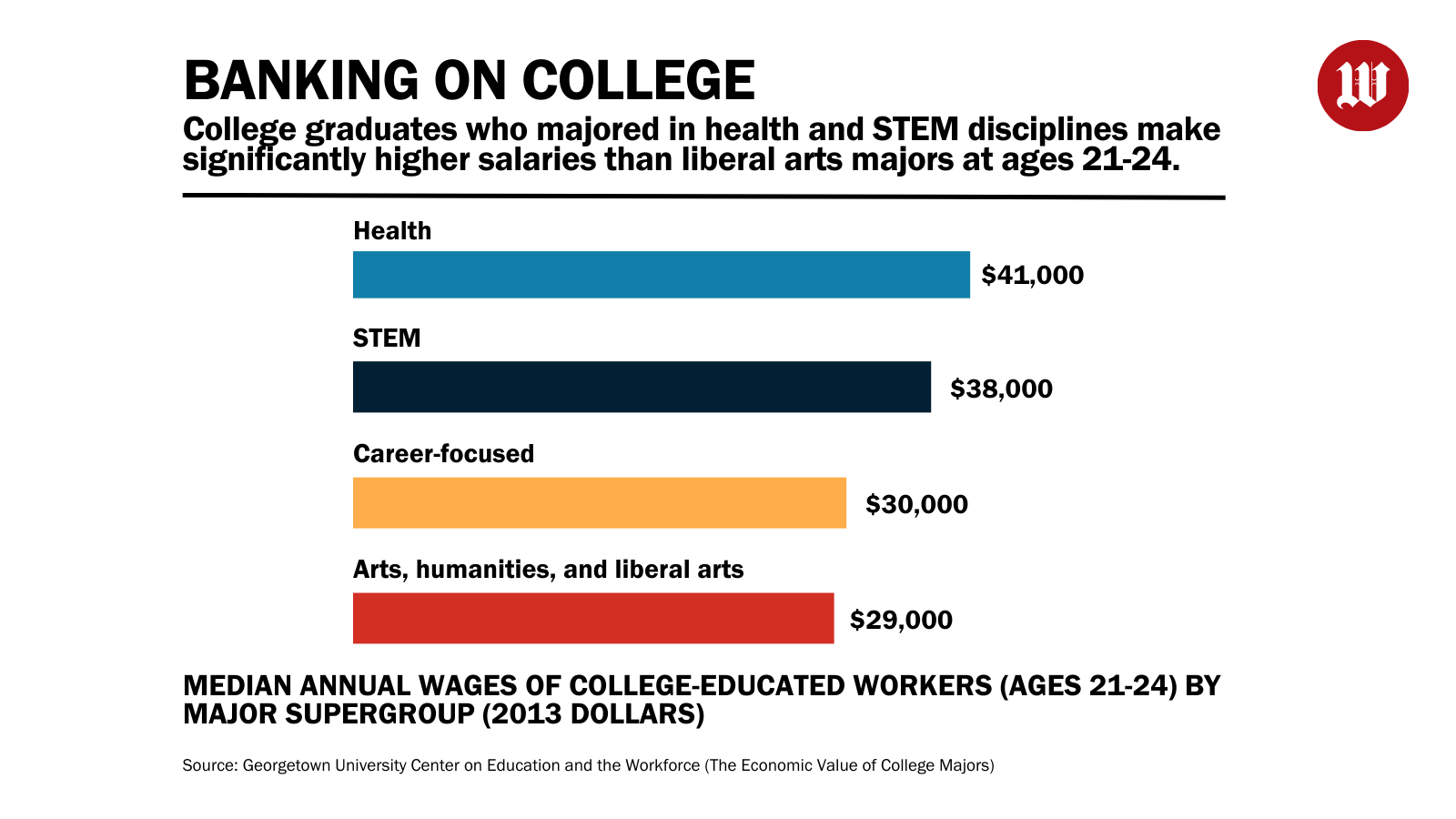

The average humanities graduate earns a starting salary of $28,000 to $48,000 a year, said Leelila Strogov, CEO and founder of AtomicMind, an education technology company.

“Humanities and social science majors are on the decline, with fewer than 30% of students pursuing them,” said Ms. Strogov, whose New York-based company prepares high school students for college admissions.

Many liberal arts graduates work in human resources, nonprofit or government jobs, writing, editing, communications or marketing, teaching, research, and business development.

As more students seek higher salaries, STEM majors comprise up to 50% of entering college students, “especially at the Ivy League and other highly selective schools,” Ms. Strogov said.

Their favored majors: computer engineering, math, statistics and the biological sciences.

“The trend appears to be college students picking majors that will lead to more obvious career paths, as opposed to blindly pursuing their passions,” Ms. Strogov said.

Following the money

Little scholarship money is available for the dwindling number of high school seniors interested in pursuing humanities majors.

Philanthropic giving to higher education jumped by 12.5% last fiscal year to $59.5 billion, the largest year-over-year increase since 2000, the Council for Advancement and Support of Education reported on Feb. 15. The bulk went to recruiting diverse students for STEM programs at wealthy schools while poorer liberal arts colleges floundered.

Carnegie Mellon University announced in February that it had received a $150 million gift to endow scholarships for STEM graduate students from underrepresented racial minorities, women and first-generation college students.

No academic expert contacted by The Times for this article could recall the last time a student received a full-ride scholarship to study English or philosophy.

“If you’re a philosophy major, maybe just expect to be driving an Uber,” said former Education Secretary William Bennett, who holds a doctorate in philosophy. “You’ll get a lot of time to read.”

The former Reagan administration official noted that four-year undergraduate costs have risen much faster over the past 15 to 20 years than food and housing prices. He blames liberal arts programs that prioritize trendy topics over critical thinking.

“Higher education is supposed to save your soul, enlarge your mind and help you tell when a man is talking nonsense,” Mr. Bennett said in an interview. “Now it’s generating nonsense.”

Theology and religion, the most popular subjects in medieval Christian education, now produce the lowest salaries of all college majors.

Graduates who majored in theology and religion earn median salaries of $36,000 five years after college, according to a New York Federal Reserve analysis. Other majors that also bring annual incomes below $40,000 after graduation are performing arts, leisure and hospitality, psychology, social services, and family and consumer sciences.

That’s less than half of what most engineering, computer science, aeronautics, applied mathematics and science graduates earn.

Meanwhile, government statistics show that the average federal student loan debt rose steadily from about $18,200 per borrower in 2007 to $37,574 last year. Although the typical federal loan is structured to be paid off in 10 years, research shows it takes an average of 21 years.

The concern about making a decent salary has led freshman Lucy McHale to major in nursing at The Catholic University of America, even though she graduated from a classical liberal arts high school in the District of Columbia.

“I would love to have stable finances so I could settle down one day,” Ms. McHale said. “College gives me the ability to receive my [bachelor of science degree in nursing] as well as the opportunity to gain internships and connections.”

The value of “knowledge for its own sake,” as ancient Greeks understood a classical education, lies in having surgeons who know ethics, defense attorneys who have mastered public speaking and politicians well-versed in history and political science.

A liberal arts education not only nourishes the soul but also develops the habits of thinking deeply, writing coherently, speaking clearly, listening carefully and making sound judgments — qualities that advocates say are valued by employers.

Yet college humanities programs have been struggling for years to attract students, with COVID-19 shutdowns exacerbating higher education’s problems. Colleges and universities nationwide are now slashing their humanities programs, and some liberal arts schools are shutting down entirely.

This three-part series examines the role that the push for STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education has played in the decline in interest in the humanities; the growing challenges that liberal arts programs face, including sky-high tuition and dropping enrollment; and efforts by conservatives and Christians to save traditional humanities education.

• Part 1: Colleges’ focus on STEM is killing liberal arts programs

• Part 2: Liberal arts programs face mounting challenges

• Part 3: Conservatives, Christians work to preserve traditional liberal arts

• Sean Salai can be reached at ssalai@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.