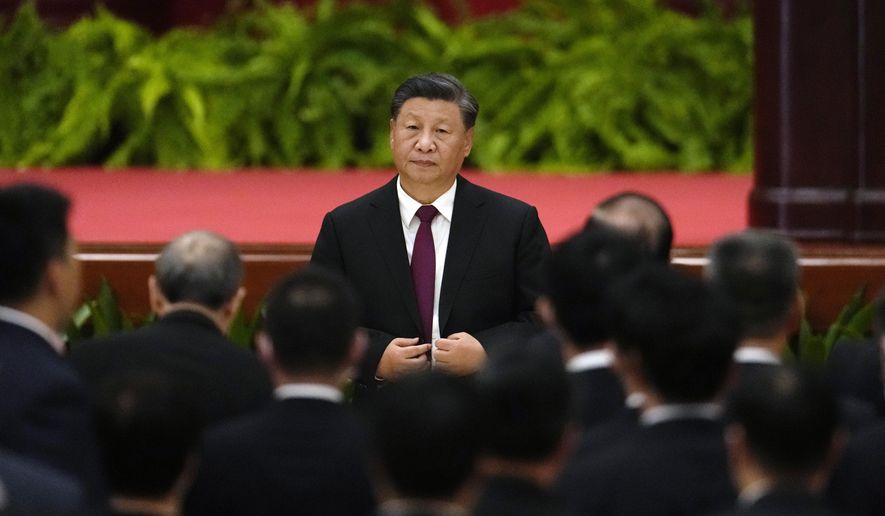

Xi Jinping has amassed unchecked power in the past decade. Now a Communist Party congress that opens Sunday in Beijing is poised to grant the Chinese president and party general secretary an unprecedented third five-year term in office despite a slowing economy and mounting domestic unrest over his zero-COVID health restrictions.

Notable achievements of Mr. Xi, who turns 70 in June, include a massive political purge of rivals in consolidating power, China’s continued rise as an economic, military and ideological challenger to the U.S., and his personal role in the government’s widely questioned handling of the COVID-19 outbreak that began nearly three years ago.

The purge ousted hundreds of people, including some of the ruling Communist Party’s most senior officials, along with senior generals of the People’s Liberation Army. More than 170 minister- or vice minister-level officials were caught in the purge, carried out under the guise of battling endemic corruption.

For the U.S. and its allies in the region, one of the more worrisome signs about the direction of China under Mr. Xi is the growing entente between Beijing and Moscow. In February, shortly before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Mr. Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin signed an agreement that called for “no limits” on cooperation between the two authoritarian states.

The Beijing-Russia axis heightened tensions with the West and increased fears that China would follow up the Russian invasion of Ukraine with a military move against Taiwan.

A key ideology of Mr. Xi’s tenure in office since 2013 is an aggressive campaign to promote Chinese communism domestically and through the trillion-dollar infrastructure plan in the developing world called the Belt and Road Initiative.

SEE ALSO: Mike Pompeo: U.S. must give Ukraine the weapons it needs to win

The political campaign is based on the Chinese Communist Party’s political doctrine called “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism With Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” The ideology was made part of the Chinese Constitution in 2018 — the same year Mr. Xi abolished term limits on his rule, opening the way for him to hold power indefinitely. Mr. Xi’s predecessors observed informal two-term limits on power.

The new ideology outlines a program for consolidating and strengthening the nation, the Communist Party and the power of Mr. Xi.

While Mr. Xi’s power grows, so do the challenges he faces. China’s once-burgeoning economy is in decline under his neo-Maoist policies, and growth is far below the heady rates of the previous three decades. The once-hot real estate market is facing a serious correction, the currency is sharply devaluating and several cities have experienced runs on banks.

Compounding the economic woes are what demographers predict is a shrinking number of people in the world’s most populous nation.

The pandemic provided another stress test for the president. Mr. Xi personally took charge of handling the outbreak of COVID-19, traced to infections from an unusual bat coronavirus in Wuhan. Critics say the Chinese government covered up and deceived international investigators early on about the origin and makeup of the virus.

Later tactics shifted to blaming the United States for the outbreak. Early samples needed to combat the virus were promised but never delivered.

In the early days of the outbreak, Chinese officials falsely reported to the World Health Organization that the virus was not transmissible to humans. Compounding that deception was the government’s failure to restrict travel from Wuhan during a major holiday after the first cases were detected. The global travel by infected Chinese transformed a regional epidemic into the worst pandemic since the Spanish flu of 1918 killed tens of millions.

A fractious party

In December, according to state media, Mr. Xi called for heightened Chinese Communist Party (CCP) unity during a central committee meeting. Such reports typically signal dissension in the ranks. During this meeting, for the first time, Mr. Xi was referred to as the “helmsman.” That leadership title had not been used since Mao was in power.

The ruling party congress that gathers Sunday is expected to officially coronate Mr. Xi not just as president of the government but also with two even more important titles in Chinese power structure: general secretary of the CCP and, crucially, chairman of the all-powerful Central Military Commission.

The authoritative newsletter SinoInsider, which accurately predicted past senior leadership actions, said in a report that Mr. Xi likely will be granted a third term in office and, contrary to Chinese rumors, there will be “no change in the general secretary’s power or status.”

“Xi Jinping will be looking to further consolidate power and strengthen his political position at the 20th Party Congress to improve his governance ability amid multiple regime-threatening crises at home and abroad,” the report said.

According to the report, the list of problems facing Mr. Xi includes not just the economic and financial crises at home but also capital flight abroad, a loss of foreign investment because of the harsh zero-COVID policies, natural disasters and energy needs, and growing geopolitical pressure over China’s campaign against Taiwan and its human rights abuses at home.

SinoInsider is predicting changes to the senior party leadership aimed at producing “quan wei,” or greater personal authority and prestige for the all-powerful president.

“The political history of the People’s Republic of China … shows that having ‘quan wei’ is more important than holding titles for a Party leader,” said the report, noting that Mr. Xi’s authority and prestige have been built on “a decade’s worth of propaganda.”

At the party congress, Mr. Xi could resurrect and assume the post of party chairman, also last held by Mao but abolished in 1982 and replaced with the current general secretary role.

Assuming the chairman’s title would effectively end what has been a collective leadership style of governance, set up by Deng Xiaoping in direct reaction to Mao’s abuses, and result in a reversion to “strongman dictatorship.”

Gordon Chang, a China expert, said Mr. Xi has consolidated his hold on power despite a record of failure as supreme leader, marked by the contracting economy, falling property prices, a currency in free fall and COVID-19 ravaging the country.

“And yet Xi is likely to get his precedent-breaking third term as general secretary this month,” Mr. Chang said. “That says the Communist Party’s political system is abnormal: The more Xi fails, the more secure his position becomes. That’s not the way things are supposed to work.”

Mr. Xi’s zero-COVID policy is massively unpopular. The state-directed effort has declared that the CCP’s power will stamp out all cases of COVID-19. The policy has resulted in lockdowns of major cities and disruptions of critical economic supply chains. Residents in the expanding number of locked-down cities are forced to remain indoors, often without access to food and other necessities.

Police dressed in white plastic hazmat suits dubbed “Big Whites” by Chinese critics have brutally enforced the zero-COVID approach. Videos reaching the West show police breaking into homes, forcing people into quarantine sites and arresting citizens on streets for suspicion of infection.

Sketchy biography

Despite the elevation of Mr. Xi and his writings in the official press, little is known about the Chinese leader’s personal life. Much of what has been published comes from propaganda sources of questionable reliability.

Mr. Xi is married to his second wife, a singer for the People’s Liberation Army known as Peng Liyuan. His only daughter, Xi Mingze, reportedly lives in the United States.

Mr. Xi’s residence in China is also said to be a state secret. A source knowledgeable about his personal life said the Chinese leader lives inside the Beijing leadership compound known as Zhongnanhai, in a house where Mao once lived. Other reports say Mr. Xi lives in an area of Beijing called Jade Spring Hill, a former imperial palace where senior party and military leaders reside.

As a child, Mr. Xi lived in relative luxury in one of those leadership compounds in Beijing. After his father, Xi Zhongxun, a close aide to Mao, was purged, Xi Jinping was sent to a remote agriculture commune in rural Shaanxi province, where he spent six years doing manual labor.

It was during the tumultuous years of Mao’s Cultural Revolution that Mr. Xi began his pathway to power.

The Cultural Revolution was the last of Mao’s mass communist campaigns, such as the disastrous Great Leap Forward. The Cultural Revolution was aimed at rooting out party officials deemed “rightist,” but it nearly destroyed the nation.

During the period from 1966 until Mao’s death in 1976, Red Guard zealots were unleashed nationwide against both party and non-party Chinese. They tore down established institutions and punished party officials, academics and others for lacking sufficient revolutionary zeal and devotion to Communist Party rule.

Red Guards at one point ransacked Mr. Xi’s home, resulting in the suicide of one of his sisters. Mr. Xi’s mother was forced to publicly denounce his father, who was among the purged officials paraded before a crowd as an enemy of the people. Xi Zhongxun was arrested and imprisoned in 1968 when Mr. Xi was 15.

The official death toll from the Cultural Revolution remains a state secret, but it killed several million people and inflicted cruel and inhumane treatment on hundreds of millions of people.

Aside from the savagery, the Cultural Revolution severely diminished China’s overall development, and the economy and society ground to a halt. By 1976, the country was on the brink of economic collapse.

A short power struggle in 1976 led to the ouster of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, and three other top officials branded as a politically evil “Gang of Four.”

The pragmatic Deng launched what is called the period of reform and opening-up. It sought to play down communist ideology, but not reject it, in favor of more market-oriented political and economic policies.

The reform period is credited with making China the world’s second-largest economy — ironically, mainly through adoption of capitalist-style economic policies.

Deng’s ideological worldview remained communist. He ordered PLA troops and tanks in 1989 to brutally put down mass pro-democracy protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Deng’s pragmatic variant of the ideology was captured in the phrase “It doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.”

Deng, who was temporarily purged during the Cultural Revolution, also adopted a strategy called “hide and bide,” concealing China’s goals and biding time while the country modernized.

Under Mr. Xi, the hide-and-bide strategy was shelved in favor of a return to more orthodox Marxism-Leninism with Chinese characteristics. Analysts say the shift tamped down China’s move toward a more open economy.

Unlike other Chinese communists who turned away from hard-core Maoism after the Cultural Revolution, Mr. Xi appears to have embraced the punishment and humiliation Mao used to maintain personal power under communist ideology.

Mr. Xi joined the CCP in 1976, the same year he took up studies at Tsinghua University. He wrote a thesis on “scientific socialism,” a euphemism for communism. Upon graduation in 1979, he went to Beijing to work for Geng Biao, a vice premier and defense minister. He held several regional party positions until his appointment in 1999 as acting governor of Fujian province on the coast opposite Taiwan.

In early 2007, Mr. Xi broke into the leadership elite after the party boss in Shanghai, Chen Liangyu, was sacked for corruption. Mr. Xi was named the replacement and by October 2007 joined the all-powerful, nine-member Politburo Standing Committee, the ultimate seat of power in China.

His fortunes continued to rise in 2008 with his appointment as vice president. By 2010, Mr. Xi achieved substantial political power by becoming one of three vice chairmen of the Central Military Commission. The CMC is the part of the CCP structure best fitting Mao’s dictum asserting that “political power grows from the barrel of a gun.”

A ‘Stalinist but no Stalin’

Mr. Xi replaced Hu Jintao as party general secretary in November 2012 and became president a year later.

One of his first actions in power was arresting two generals who shared the CMC vice chairman’s post.

Gen. Guo Boxiong, CMC vice commissioner, was sent to prison for life in 2016 for bribery, and Gen. Xu Caihou, vice commissioner, was investigated for bribery but died from cancer in 2015 before he could be fully purged.

The removal of both generals ended a 10-year stretch of their strategic control over PLA promotions that provided enormous power within the communist system.

Mr. Xi then began selecting a generation of PLA officers loyal to him as he systematically consolidated power.

Mr. Xi also targeted China’s semiprivate companies and newly made millionaires and billionaires. He forced some to leave the country or turn over their companies and fortunes to the party’s control. He ordered Chinese companies to set up internal CCP committees, which could be used to control policies and the business moguls who made billions of dollars during the Deng era.

Some of China’s best-known business magnates were imprisoned for merely criticizing Mr. Xi’s policies. One leader of the conglomerate HNA, Wang Jian, died mysteriously in a fall while visiting France. Jack Ma, founder of the financial firm Ant Group and the e-commerce company Alibaba, disappeared from public view for months at one point during the crackdown.

Mr. Xi’s political message was clear: Those following the capitalist road are operating outside official ideology and must toe the political line or face retribution.

The Chinese president has overseen what U.S. military leaders call the largest buildup of arms and forces by any nation since the Cold War. Mr. Xi oversaw the reorganization of China’s regional military command system and made sure weapons were developed and built at a rapid pace.

New missiles, warships, submarines, jet fighters and bombers have been deployed in large numbers and with sophisticated weapons technology.

The buildup’s most ominous feature has been an unprecedented expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal. Adm. Charles Richard, the commander of U.S. strategic nuclear forces, described it as “breathtaking” in size and speed of development.

China’s military under Mr. Xi has directly challenged the United States, Japan and other nations with creeping territorial expansionism in the South China Sea, in the East China Sea and toward Taiwan. Mr. Xi has targeted the island democracy for a takeover — using force, if necessary.

Despite Beijing’s many challenges, some China watchers say economic collapse or even the ouster of Mr. Xi is unlikely. “Instead, the expectation is for years of stagnation, like Japan in the 1990s and 2000s,” one U.S. official said.

As for Mr. Xi’s announced promise to take over Taiwan in the coming years: “I don’t think Xi’s disposition towards forcible annexation of Taiwan is linked to the strength of the [Chinese] economy, but others may disagree. He’ll do it if he is absolutely confident he can succeed, whether his economy is good or bad,” the official said.

Mr. Xi has carried out his policies under the “Chinese dream,” a nationalist play on the idea of the American dream, to make China the world’s leading superpower under the Communist Party’s ideology.

The Chinese dream promotes Chinese communism as superior to American democracy, which proponents of the Chinese dream have criticized as a failure of capitalism — the chief ideological rival of communism and state control.

Bernard Cadogan, a Britain-based former adviser to the New Zealand government who has studied Chinese affairs closely, said Mr. Xi is a “Stalinist but he is not Stalin.”

“Xi is not in his league,” Mr. Cadogan said. “Xi emphasizes very traditional nationalist cultural practices and values. So did Stalin. If you turned on Radio Moscow in 1950, you would have heard a lot of folk music. Xi is into this, too.”

The difference is Stalin was riding the momentum of the Bolshevik Revolution and the intelligentsia were in a modernist ferment, he said.

“Xi’s revolution happened a long time ago,” he said. “The original revolutionaries are dead, and Xi is fearful of new trends.”

• Bill Gertz can be reached at bgertz@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.