Georgia’s toss-up Senate race, marked by mudslinging and scandals, heads toward a conclusion with the start of early voting Monday in a contest that will help determine which party controls the upper chamber of Congress.

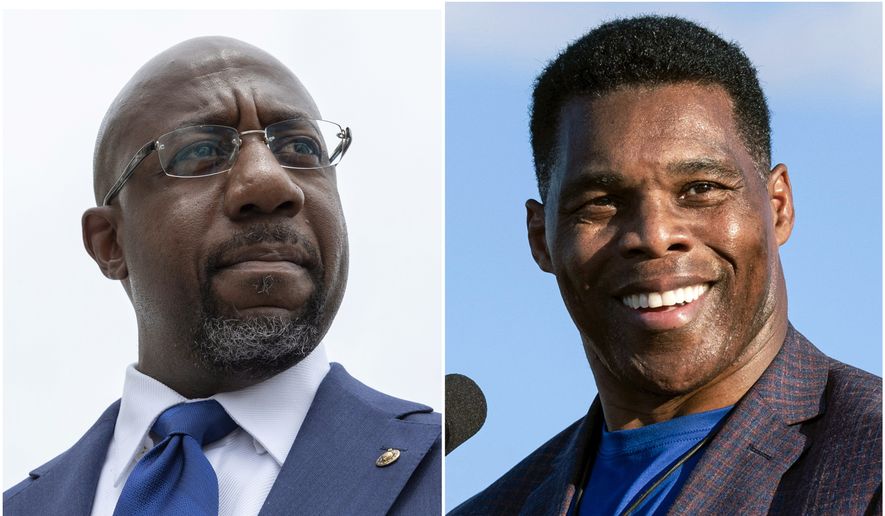

Republican Herschel Walker and Democratic Sen. Raphael G. Warnock have remained neck and neck in the polls amid the crossfire of negative campaign ads and carefully timed opposition research dumps.

The debate between the two men Friday in Savannah was a slugfest, and a portion of it was dedicated to questioning the candidates about scandals that have surfaced in news reports and campaign ads.

The latest damaging revelation about Mr. Warnock, published in The Washington Free Beacon, was that Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Mr. Warnock earns a salary as a senior pastor plus a $7,417 monthly housing allowance, has tried to evict low-income residents from a church-owned apartment building over past-due rent as low as $28.55 a month.

Mr. Warnock did not specifically rebut the story at the debate but called the accusations “desperate” and said Mr. Walker and the Republican Party “are busy trying to sully Ebenezer Baptist Church,” where civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. was a pastor.

Mr. Walker recently spent much of his campaign defending himself from a claim that he paid for a girlfriend’s abortion and urged her to undergo the procedure for a second pregnancy. Mr. Walker, who runs on a pro-life and pro-family platform, also has been accused by his son of being an absentee father, and a Warnock campaign ad has highlighted past accusations of domestic abuse.

On Friday, he denied the claim about an abortion payment.

Mr. Walker recently ran an ad spotlighting claims by Mr. Warnock’s ex-wife that he did not pay child support and that he ran over her foot with his car. Mr. Warnock did not directly answer a debate moderator who asked about the missed child support payments.

The scandals have dominated the race and nearly drowned out the candidates’ policy differences until they reached the debate stage.

Mr. Warnock and Mr. Walker sparred on inflation, drug prices, voting rights, crime, abortion and student loans.

Mr. Walker, a former college football star and NFL player, took the stage with expectations that the was no match for the more polished Mr. Warnock, who has more than a year of experience in the Senate and decades as a prominent pastor.

On the campaign trail, Mr. Walker kept expectations low. He told supporters that he is not a typical politician and takes pride in his rural Georgia roots. He talks about the need for redemption and acknowledges his imperfect past.

In the debate, he suggested that Mr. Warnock’s support of unlimited abortion belied his role as a Christian pastor and accused him of evading answers to key questions. He tied Mr. Warnock to President Biden, who is unpopular in the state, and to the spending and energy policies that have led to inflation and high gas prices.

Mr. Warnock declined to answer moderators’ questions about whether he backed the far-left proposal to expand the Supreme Court or believed Mr. Biden should run for a second term.

Mr. Walker pointed across the stage at Mr. Warnock.

“When you get to Washington, you have to become a leader,” Mr. Walker said. “Being a leader, you have to make tough, tough decisions. Do you see that answer there? He really didn’t give you an answer. So my answer is no.”

Mr. Warnock, who grew up in public housing as one of 12 children, has campaigned on his personal success story and his readiness to serve in the Senate.

He brought that strategy to the debate stage by pledging to support an expansion of Medicaid in Georgia and to work to reduce the high cost of college tuition, lower prescription drug prices and provide other government services for the working class and the poor that helped him rise from poverty.

Mr. Warnock blamed high gas, grocery and drug prices partly on corporate greed.

“I’ve stood up for hardworking families every single day, and I’ve stood against the corporations that are being bad actors,” he said.

The Senate race in Georgia is one of the most competitive of the midterm elections. The once reliably Republican electorate has become populated by more Democrats because of newcomers to Atlanta and its suburbs.

Republicans held the two Senate seats for nearly two decades until January 2021, when Mr. Warnock and Democrat Jon Ossoff won special elections for both seats, defeating Republicans David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler.

The divided electorate still tilts red, and Republicans believe the country’s economic woes will drive voters to their ticket and increase party turnout.

Mr. Walker may also benefit from Gov. Brian Kemp’s coattails.

The Republican, who is running for a second term, has led Democratic opponent Stacey Abrams by several percentage points in most polls.

In an interview with The Washington Times, Mr. Kemp declined to comment specifically on Mr. Walker’s race. He said he believes Republicans are in a far better position with on-the-ground campaign resources than they were in 2021 when Mr. Perdue and Ms. Loeffler were defeated.

“We’ve been working ever since the 2020 election to raise money and build our own ground game that’s going to help the whole ticket,” Mr. Kemp said.

For some Georgia voters, the mudslinging has been little more than background noise.

Steve Adams, who works in a modular building factory in Pearson, a town in rural southern Georgia about 55 miles from the Florida line, said he doesn’t believe all the negative campaign attacks.

“We’ve all got a shady past somewhere, and that stuff can be dug up on anybody,” Mr. Adams said. “Some more than others.”

• Susan Ferrechio can be reached at sferrechio@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.