OPINION:

In today’s curriculum wars, critical race theory is talked about a lot. Proponents present CRT in mild language. But the philosophy comes from Karl Marx’s demand that everything be “ruthlessly” criticized, so it is a ruthless criticism of America. Slavery and the Jim Crow era are dark spots in U.S. history that we do need to teach. But America’s overarching story is one of hope.

Last month, the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty released a study that we authored about flawed social studies, curricula and textbooks, as well as offering some more hopeful lessons. How can a lesson be more hopeful, you might ask? Well, let us show you.

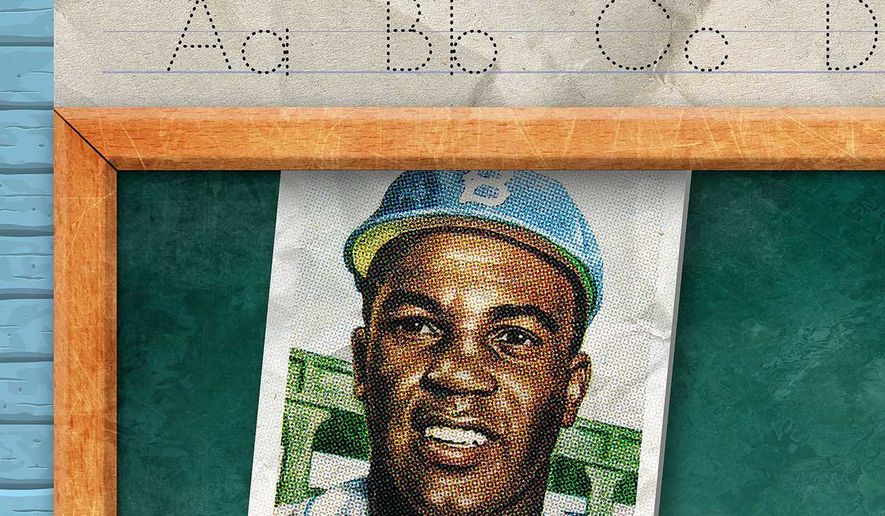

The baseball season went out with a bang when the Houston Astros won game six on Nov. 5. This year is one of special importance for the sport: It is the 75th anniversary season of desegregating baseball. 1947 was the year the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson as the first African American player in Major League Baseball (MLB). Is it possible that Adam Smith, the father of economics, was a help to Robinson and the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Branch Rickey, in desegregating professional baseball?

It took the courage of Robinson and Rickey to make the move. Would fans buy tickets to see racially integrated teams? How would other players react?

Adam Smith wrote “The Wealth of Nations” 143 years before Robinson was born. Smith’s invisible hand theory states that allowing people to act in their own interest often promotes positive social outcomes even when they are unintentional, which is associated with how the profit motive operates in a market economy.

Racial segregation was widespread after the Civil War. It would take many years, constitutional amendments, Supreme Court rulings and federal legislation to end the Jim Crow era. But why would some labor markets — such as MLB — act more quickly than others?

According to basic principles of economics, people respond to incentives in predictable ways. Owners of MLB teams want to make a profit, and they want to win. Players want better salaries, and they are eager to win, too.

In a normally functioning labor market, employers strive to hire the most productive worker at the lowest cost. Imagine that you are the owner of an MLB team. You know that great athletic talent is nearby, and that the talent wants to work for you and could help you win. Some club owners at the time wanted to hire the best players regardless of race, but they had an agreement to sign only White players. Few wanted to cross that barrier.

Even though MLB clubs operated a legal cartel (due to a peculiar 1922 Supreme Court ruling), there was a surprising amount of competition in the game. There was competition from the semi-pro leagues that integrated as early as 1935. The Negro Leagues were also popular among fans. Competition erodes the ability of a cartel to enforce the agreements among its members.

Competition in big baseball markets like New York was especially intense. After World War II, New York City had three professional baseball teams: the Brooklyn Dodgers, the New York Yankees and the New York Giants. Fans love to follow winning teams.

In 1946, the Brooklyn Dodgers finished two games behind the Cardinals in the National League pennant race. They hoped to do better. In 1946, Rickey signed Robinson, who had played that year with the minor-league Montreal Royals. In 1947, Robinson became the largest attraction in baseball overnight. Huge crowds turned out to see him play. The Dodgers won the National League pennant that year. They won it again in 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955 and 1956. The Dodgers won the World Series in 1955.

Rickey was aware of his success. He quickly signed more African American players, such as Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe. Economists James Gwartney and Charles Haworth found that on average, each added African American player on a team was associated with between 55,000 and 60,000 more annual home-team admissions in the 1950s.

Mr. Gwartney and Haworth also found that the number of African American players was a significant factor in determining the number of games won. For the period from 1950 through 1955, they found that the inclusion of an African American player on a major league team, on average, resulted in 3.75 more wins per year.

Markets punish profit-seeking businesses that discriminate based on race, gender, sexual orientation or religion. Racial discrimination often requires the force of law to sustain it for the long term. Smith’s invisible hand and market competition were a big help to Robinson and Rickey in ending racial discrimination in MLB. This is a much more hopeful message about markets and race than is often emphasized in today’s polarized nation. If teachers brought lessons like this into the classroom, they could bridge racial barriers and bring students together.

• Schug is a professor emeritus at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and Niederjohn is a professor of economics and director of the Free Enterprise Center at Concordia University, Wisconsin.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.