OPINION:

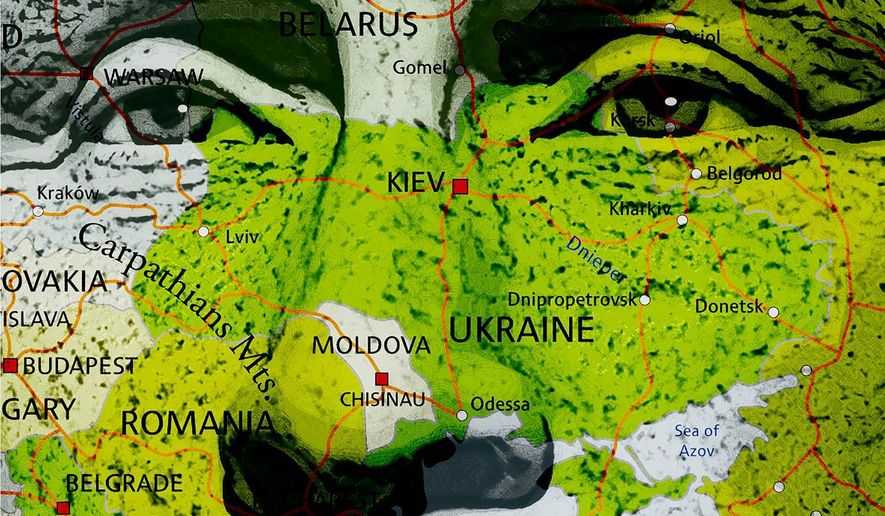

Russian President Vladimir Putin and his generals have fallen back on familiar strategies in their effort to stanch Ukraine’s counteroffensive. They’re making liberal use of cannon fodder, in the form of new conscripts swiftly sent to plug gaps at the front. And they are targeting civilians and civilian infrastructure in an attempt to break Ukrainian morale.

In the hopes of getting the West to lessen materiel support to Kyiv and press for a settlement, Moscow is using a combination of old and new tactics: bellicose nuclear rhetoric and hybrid attacks such as the recent mysterious sabotage of undersea cables and pipelines.

Another facet of Russia’s hybrid war against the West is its cynical use of migrants from Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East to destabilize Europe. For Russia, the weaponization of migrants is nothing new. A side benefit for Mr. Putin in his intervention to save Syrian ruler Bashar Assad is the ability to ratchet pressure up and down, pushing migrants outside the war-torn region toward European shores. The same can be said for Russia’s interest in North Africa and the Sahel.

For many European nations, particularly those with Mediterranean coastlines, a significant stream of new migrant arrivals has been a constant for many years. The resultant economic, humanitarian, security and social challenges have never been fully met. Russia sits as a gatekeeper of Europe’s southern approaches. The thought of Mr. Putin igniting new migrant flows surely keeps many European leaders up at night.

It is not only in the Mediterranean, however, that Russia’s weaponization of migrants is on display. Even countries like Finland and Norway have seen their share of illegal migrant crossings aided by Russia.

Russia’s hybrid warfare with human pawns also rages along the borders between the Russian proxy state of Belarus and Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. A year ago, when Russia-Belarus first opened this front, I wrote:

“For the past four months, Belarus has been … encouraging migrants from Afghanistan, Africa, and the Middle East to travel to Minsk … and then driving them, via buses and the butt of a rifle, to the border with neighboring Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. There, Belarusian authorities beat the migrants, deny them necessities, and at times physically force them to try to breach the border illegally.”

Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine a few months later pushed this hybrid attack out of the headlines. But it has not gone away. In June, Poland completed a permanent steel border fence with Belarus. Touring the wall, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki remarked that “the first sign of the war in Ukraine was (Belarus President) Alexander Lukashenko’s attack on the Polish border with Belarus.”

In late August, Lithuania announced the completion of a border wall with Belarus (at least the parts of the border that aren’t a body of water).

Latvia’s construction of a border wall facing Belarus, while not completed, is underway. Latvia has a shorter border with Belarus than either Lithuania or Poland. In September, Riga reported that it was stopping 60 to 80 illegal migrant crossing attempts per week.

The completion of physical barriers does not mean that Mr. Lukashenko and Mr. Putin have decided to abandon this theater of hybrid warfare. Belarusian security forces continuously cut or damage sections of fencing before forcing more migrants across. The walls, though, have had a measurable impact. In August, Poland stated that it was seeing around 80 crossing attempts per day, down from 800 a day before the completion of the border wall.

While Poland’s border with Kaliningrad remains quiet for now, Russia’s recent announcement that it was launching flights from the Middle East and North Africa to Kaliningrad (hardly a top tourist destination) points to a likely Russian plan to open a new hybrid front against Poland. Polish authorities are therefore taking no chances. Warsaw has announced plans to build a 130-mile fence along the Poland-Kaliningrad border, and construction began this month.

Considering Russia’s barbarism in Ukraine, to say Mr. Putin has little regard for human life is clearly an understatement. Russia’s and Belarus’ continued use of human pawns as weapons to pressure and probe Europe is despicable. Unfortunately, it looks like it’s here to stay.

• Daniel Kochis is senior policy analyst for European affairs in The Heritage Foundation’s Thatcher Center for Freedom.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.