“Lay aside for a while the burden of self-improvement and instruction, simply to marvel and enjoy.”

That’s the wise counsel of English FM and author Steve Giddins, whose new 45-game anthology, “The Most Exciting Chess Games Ever” (New In Chess, 201 pages, $24.95), is a welcome break from a chess world that sometimes seems too much with us, whether it’s ugly cheating scandals and lawsuits or that nagging stack of endgame exercise books on minor piece endings with unbalanced pawn structures which we swear we will get around to soon. We “work at” our chess a little too much sometimes, and every so often it’s useful (and instructional, I might add) to be reminded of the great struggles and amazing moves that got us hooked on the game in the first place.

The book is simplicity itself: New In Chess magazine has long had a feature polling top players on their likes and dislikes, including “the most exciting chess game you ever saw.” The result: an intriguing mix of the ultrafamiliar (Anderssen-Kieseritzky 1851, Byrne-Fischer 1956, Topalov-Kasparov 1999) and some unexpected gems, including a far lesser-known Anderssen win over Rosanes in 1863, nominated by Dutch IM Willy Hendriks, and a 2020 game between silicon heavyweights Leela Zero and Stockfish, suggested American IM and Chess.com head honcho Danny Rensch.

None of the games are perfect — the modern engines guarantee that — but all reflect the glory of chess as we play it, with plot twists, sharp turns of fortune, and lightning shafts of brilliance that make us eager to get back to the board ourselves. I found the best of Giddins’ book to be the lesser-known offerings, including American IM John Donaldson’s pick: a wild slugfest between two lesser-known Russian masters at an obscure 1967 event, one that packs an amazing amount of drama into just 25 moves.

The opening was actually standard theory at the time in a venerable Two Knights Defense line, but Black goes astray with the premature 10. Ne5 Qd4? (both 10…Bd6 and 10…Bc5 are better) 11. f4 Bc5 12. Rf1! — White gives up the right to castle, but Black’s advanced pieces are about to be pushed back. The engines aren’t kind to either player, but that’s because both are presented with bewildering choices in an increasingly irrational position.

Thus: 13. c3 Nd5?! 14. Qa4! (giving the king an escape square from the coming Black queen check on h4, while pressuring Black’s minor pieces in major ways; bad was 14. b4? Qh4+ 15. g3 Qxh2 16. Qa4 Bh3 17. bxc5 Bxf1 18. Bxf1 Qxg3+ 19. Kd1 Qxf4, and Black is winning) 0-0 15. b4? (tempting but wrong; better was 15. Qxe4! f6 16. Bd3 fxe5 17. Qh7+ Kf7 18. fxe5+ Ke6 19. Qg6+ and the king hunt is on) Qh4+ 16. Kd1 Rd8!, with the cute threat of 17…Ne3 mate. White get his extra piece, but his king is driven to a3 and his queenside pieces are a massive jumble. As both sides search for the knockout blow, the win swings from player to player before a brilliant tactic decides the matter.

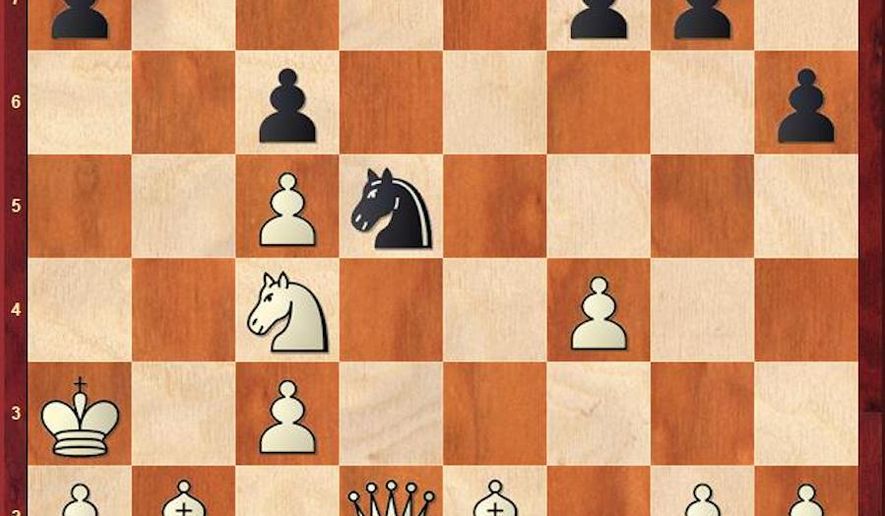

On 22. Rd1 Bc2! 23. Qxc2, 23…Qe7!, hitting the c-pawn, would have won at once, as 24. Ne3 Nc4+ 25. Ka4 Qb7+ mates. Instead, the tension gets to both combatants on 23…Nb3?? 24. Nc4?? (returning the favor; White holds the game together with 24. Nxc6!, with lines like 24…Nxa5 25. Bxa1 Qf8 26. Nxb8 Qxc5+ 27. Kb2 Rxb8+ 28. Qb3 Rxb3+ 29. axb3, with a rook and two minor pieces for the lost queen) Nxa1 25. Qxd2 (see diagram; now it’s just a draw on 25…Qe7?! 26. Nd6 Qc7 27. Ka4! Nb6+ 28. Kb4 Nd5+ 29. Ka4, but Black has better…) Qb6!!, and White resigned as mate’s on the way after 28. Nxb6 (Black’s threat is just 28…Qa6+ and wins; also falling short are both 28. cxb6 axb6+ 27. Na5 Rxa5 mate; and 26. Ka4 Qb5+ 27. Ka3 Qa6+ 28. Na5 Qax5 mate) axb6+ 27. Ba6 Rxa6 mate.

—-

The template for “The Most Exciting Chess Games Ever” was set by one of my all-time favorite books as a young, aspiring D-class player swept up in the Bobby Fischer boom: English author R.N. Coles’ “Epic Battles of the Chessboard.” As with Giddins’ new book, Coles wasn’t looking to instruct or preach, but was simply in the hunt for what he called “rattling good games.”

“Here may be seen,” Coles wrote, “how the masters react when a combination goes wrong or when their opponents fight back; In these games neither player is content to be smothered by the brilliant imagination of the other, nor to allow master technique to win a won game by copybook methods. Here is complicated, fighting chess.”

Again, the anthology is a mix of the well-known and largely overlooked. In the second category, we have always liked Belgian great Edgar Colle’s epic battle (to coin a term) with Swedish master Gosta Stoltz from a 1931 tournament in Bled, Yugoslavia. Once again, a number of both inspired and misconceived ideas are packed into just a relative handful of moves. Enjoy.

At first it seems there won’t be much to see in this unusual Alekhine Defense sideline, as after 17. g4 hxg4 19. Rdg1 it appears Colle and his compromised kingside are about to be swept off the board. But Black hangs tough with 19. Nxg5 Ne5 (covering g4, g6 and hitting the White bishop) 20. Be4 Ba6! (c6 21. f4 Rxf4 22. Qh2 and the attack continues unabated) 21. Bxa8 Nd3+ 22. Kb1 Qxa8, and for the investment of an exchange, Black suddenly has some nasty counterthreats. The fight for the initiative becomes ferocious on 24. Qc3 (setting a very nasty pin) Rf5 25. f4?! (mistimed; better was 25. Re1 Kg8 26. Rhg1 d6 27. cxd6 cxd6 28. Qd4, and the Black d- and e-pawns are attacked) gxf3 26. Re1 f2. White now thinks he has a knockout punch in store, only to find himself on the canvas instead in the wild finale: 27. Rxe5 Kg8! (Qxh1+?? 28. Re1+ Kf8 29. Rxh1 wins for White) 28. Rf1? (28. Ne4! is the only way to keep the game going, with a lot still to be decided after 28…f1=Q+ 29. Rxf1 Rxf1+ 30. Kc2 Qf8 31. c6 d5 32. Nd2) Qg2 29. Qd3 (seemingly covering everything, as 29…Rxe5?? allows mate in two after 30. Qxg6+) Bxc4!! (a piece languishing backstage suddenly takes a starring role, with a critical deflection of Stoltz’s queen) 30. Qxc4 Rxe5 31. Qd3 (one last try to target that weak g-pawn, but it’s now too late) Qxf1+!, and White resigned facing 32. Qxf1 Re1+ 33. Kc2 Rxf1 34. Ne4 Rc1+ 35. Kxc1 f1=Q+ and wins.

Again, there was nothing perfect about the play, but the fighting spirit of the players was impeccable.

(Click on the image above for a larger view of the chessboard.)

Fomenko-Radchenko, Sochi, Russia, 1967

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Nf6 4. Ng5 d5 5. exd5 Na5 6. Bb5+ c6 7. dxc6 bxc6 8. Be2 h6 9. Nf3 e4 10. Ne5 Qd4 11. f4 Bc5 12. Rf1 Qd8 13. c3 Nd5 14. Qa4 O-O 15. b4 Qh4+ 16. Kd1 Rd8 17. Kc2 Bf5 18. bxc5 e3+ 19. Kb2 Rdb8+ 20. Ka3 Qd8 21. Bb2 exd2 22. Rd1 Bc2 23. Qxc2 Nb3 24. Nc4 Nxa1 25. Qxd2 Qb6 White resigns.

Stoltz-Colle, Bled, Yugoslavia, August 1931

1. e4 Nf6 2. e5 Nd5 3. c4 Nb6 4. c5 Nd5 5. Nc3 Nxc3 6. dxc3 Nc6 7. Nf3 g6 8. Bc4 Bg7 9. Bf4 O-O 10. Qd2 b6 11. h4 h5 12. O-O-O e6 13. Bg5 f6 14. exf6 Bxf6 15. Qc2 Qe8 16. Bd3 Kg7 17. g4 hxg4 18. Rdg1 Bxg5+ 19. Nxg5 Ne5 20. Be4 Ba6 21. Bxa8 Nd3+ 22. Kb1 Qxa8 23. c4 Ne5 24. Qc3 Rf5 25. f4 gxf3 26. Re1 f2 27. Rxe5 Kg8 28. Rf1 Qg2 29. Qd3 Bxc4 30. Qxc4 Rxe5 31. Qd3 Qxf1+ White resigns.

• David R. Sands can be reached at 202/636-3178 or by email at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

• David R. Sands can be reached at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.