(Editor’s note: David Sands is off this week, solving a particularly fiendish mate in 17. This column originally ran on March 11, 2014.)

World champion visits Philadelphia. Sportingly agrees to a match with a local star. Gets clocked.

It sounds like the plot of a “Rocky” movie, but I discovered Sylvester Stallone’s screenplay eerily prefigured while perusing some 140-year-old chess columns from the Baltimore Sunday News.

Last month, I made my first pilgrimage to the Cleveland Public Library to browse the world-renowned John G. White Chess and Checkers Collection, an astounding compilation of chess books, historical records, memorabilia and equipment hard by the banks of Lake Erie.

A bucket-list item for any serious acolyte of Caissa (you just start talking this way when you read enough 19th century chess literature), the collection begun by local attorney John G. White now includes over 32,000 volumes and bound periodicals dating from the very origins of the game.

Librarian Kelly Ross Brown kindly pulled out some of the collection’s archives of Washington and Baltimore area chess columns from the 1850s through the 1990s, supplying enough raw material for a half-dozen more columns to come.

It was the Dec. 9, 1883, Baltimore column by C.E. Dennis that recounted the first visit to Philadelphia by then-reigning Austrian world champion Wilhelm Steinitz, who had moved from Europe to New York earlier in the year. Steinitz reportedly played (and won) a lot of casual games against the locals, but was put on the canvas by local competitor J.A. Kaiser.

“A serious illness of our nearest and dearest relative has prevented us from examining these games critically, and devoting the usual amount of time to the preparation of our chess column,” Dennis wrote in his column that week. We’re happy to pinch-hit.

Steinitz helped develop many of the principles of modern chess, and was famous for accepting cramped and ugly positions in pursuit of his positional goals. He’s in a trademark crouch in this Ruy Lopez after 12. Ne2 Nc8 13. Be3 Be7 14. 0-0 0-0 15. Nf4, but might have done better to slow down White’s initiative with 15…bxc4 16. Bxc4 Bxc4 17. Qxc4 Bf6 18. Nh5 Bxb2 19. Rab1 Be5 20. f4 d5, with a defensible game.

Kaiser takes the play to the champion, whose defensive prowess is not much in evidence here: 17. Nh5 Bd8 18. Bh6!? (Rfc1 bxc4 19. Qc3 f6 20. Bxc4 d5 21. exd5 cxd5 22. Bxa6 is also good for White, but Kaiser wants more) gxh6 (White also gets good compensation on 18…bxc4 19. Qg3 g6 20. Ba4 Re8 21. Qc3 f6 22. Nxf6+ Bxf6 23. Qxf6 Qe7 24. Qc3) 19. Qg3+ Bg4 (Bg5?? 20. Nf6+), when White could have nailed down an advantage with 20. Bd1! Qe6 21. Bxg4 Qg6 22. cxb5 axb5 23. Rfd1 Be7 24. Qf3, with the nasty positional threat of 25. Bf5.

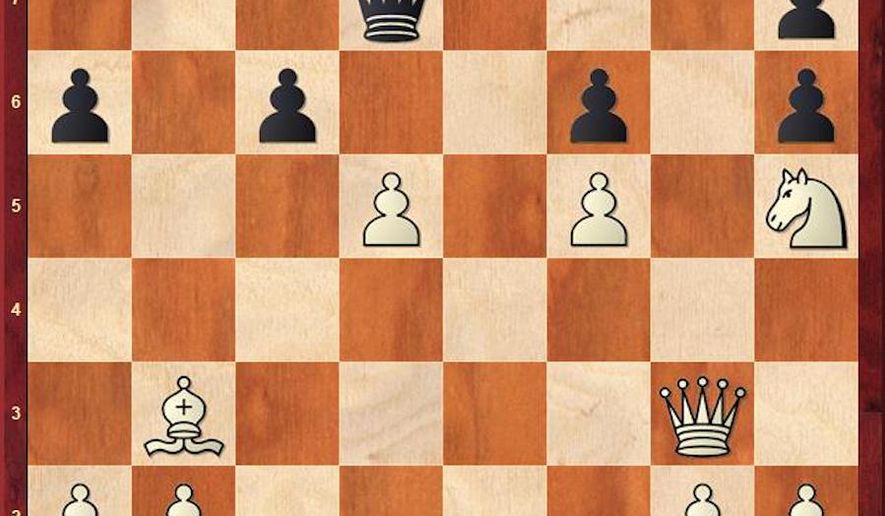

Instead, the play gets a little ragged on both sides before Black overlooks a killer shot — 20. f3?! Kh8? (bxc4 21. Bxc4 d5 22. exd5 Rb4! 23. b3 cxd5 24. Bd3, with only a minimal edge for White) 21. fxg4 f6 22. cxb5 Rxb5 23. Rf5 Rxf5? (this was clearly not the champ’s day; 23…Qe8 24. Qf3 Bb6+ 25. Kh1 Bd4 leaves Black in fine shape) 24. gxf5 d5 25. exd5 (see diagram) Rg8?? (Black holds with 25…Nd6 26. Qd3 cxd5 27. Ng3 Bb6+) 26. Qxg8+!.

The unfortunate position of Black’s queen leads to instant resignation, in light of 26…Kxg8 27. dxc6+ Qf7 28. Rd1 Be7 29. Bxf7+ Kxf7 30. Rd7, with a won game; e.g. 30…Nb6 31. Rb7 Nc8 32. Rb8 Na7 33. c7 and wins.

—-

In his column just a week later, Dennis recounts another David vs. Goliath battle, this one between local Baltimore champ Alexander Sellman (still one of the strongest players Charm City ever produced) and Polish grandmaster Johannes Zukertort. Zukertort was Steinitz greatest rival, losing two epic title matches to the Austrian. Like Steinitz, Zukertort won most of his games from the locals, but Sellman outplays him here.

Zukertort as White adopts a surprisingly modern handling of the Colle System (the 5. b3 line is now known as the Colle-Zukertort variation), temporarily sacrificing a pawn after the provocative 13. e4 Nxd4!? (probably the liveliest of the many ways Black could have taken to resolve the central tension) 14. Nxd4 cxd4 15. cxd5 Rxc1 16. Rxc1 exd5 17. e5, and Black’s doubled central pawns are as much a target as an advantage.

Sellman gives back the pawn to open up the board for his two bishops, and White gets tripped up trying to ease Black’s pressure along the d-file: 21. Bxd4 (Nxd4? Bg5 22. Nxe6 Bxd2 [fxe6 23. Qd1 Bxc1] 23. Nxd8 Bxc1 24. Bxc1 Rxd8 and Black wins) Re8 22. Be3 d4!? 23. Nxd4 Nxd4 24. Bxd4 Qd5 (of course not 24…Qxd4?? 25. Bh7+) 25. Bf1 Rd8 26. Rd1 a5 27. bxa5 bxa5 28. Bc3?! (better was 28. Qb2 a4 29. Rd2 a3 30. Qb6 Qc6 31. Rd3 Qxb6 32. Bxb6, keeping things level) Qc6, when White has to go in for 29. Qxd8+ Bxd8 30. Rxd8+ Kh7 31. Bxa5 Qc5 32. Rd7 Qxa5 33. Rxb7 Qxa2, with balanced play.

Instead, Zukertort relies on a tactical trick that doesn’t come off: 29. Qc1? Rxd1 30. Qxd1 Qxc3 31. Qd7 (a double attack, but Black has a counter) Rxd1 32. Qxd1 Qxc3 31. Qd7 Qb4 32. a3 Qb1! (“a masterly stroke,” according to Dennis) 33. Qxe7 Ba6, and White is losing a piece. Zukertort’s struggles to generate new counterplay go nowhere, and after 39. Qxa5 Qg6 40. Qa8 Bd3 41. Qb7 Qd6+, White resigns facing 42. Kh1 Qxa3 43. Qd5 Qc1+ 44. Kh2 Qf4+ 45. Kg1 Be4, and Black wins easily.

Kaiser-Steinitz, Phildelphia, 1882

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 a6 4. Ba4 Nge7 5. d4 exd4 6. Nxd4 Nxd4 7. Qxd4 b5 8. Bb3 d6 9. c4 Be6 10. Qd3 Qd7 11. Nc3 c6 12. Ne2 Nc8 13. Be3 Be7 14. O-O O-O 15. Nf4 Bf6 16. Rab1 Rb8 17. Nh5 Bd8 18. Bh6 gxh6 19. Qg3+ Bg4 20. f3 Kh8 21. fxg4 f6 22. cxb5 Rxb5 23. Rf5 Rxf5 24. gxf5 d5 25. exd5 Rg8 26. Qxg8+ Black resigns.

Zukertort-Sellman, Baltimore, 1883

1. d4 e6 2. Nf3 d5 3. e3 Nf6 4. Bd3 c5 5. b3 Nc6 6. O-O Be7 7. Bb2 O-O 8. c4 b6 9. Nbd2 Bb7 10. Rc1 Rc8 11. Qe2 h6 12. Rfd1 Ne8 13. e4 Nxd4 14. Nxd4 cxd4 15. cxd5 Rxc1 16. Rxc1 exd5 17. e5 Bc5 18. Nf3 Nc7 19. Qd2 Ne6 20. b4 Be7 21. Bxd4 Re8 22. Be3 d4 23. Nxd4 Nxd4 24. Bxd4 Qd5 25. Bf1 Rd8 26. Rd1 a5 27. bxa5 bxa5 28. Bc3 Qc6 29. Qc1 Rxd1 30. Qxd1 Qxc3 31. Qd7 Qb4 32. a3 Qb1 33. Qxe7 Ba6 34. h3 Qxf1+ 35. Kh2 Qxf2 36. e6 Bf1 37. exf7+ Qxf7 38. Qd8+ Kh7 39. Qxa5 Qg6 40. Qa8 Bd3 41. Qb7 Qd6+ White resigns.

• David R. Sands can be reached at 202/636-3178 or by email at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

• David R. Sands can be reached at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.