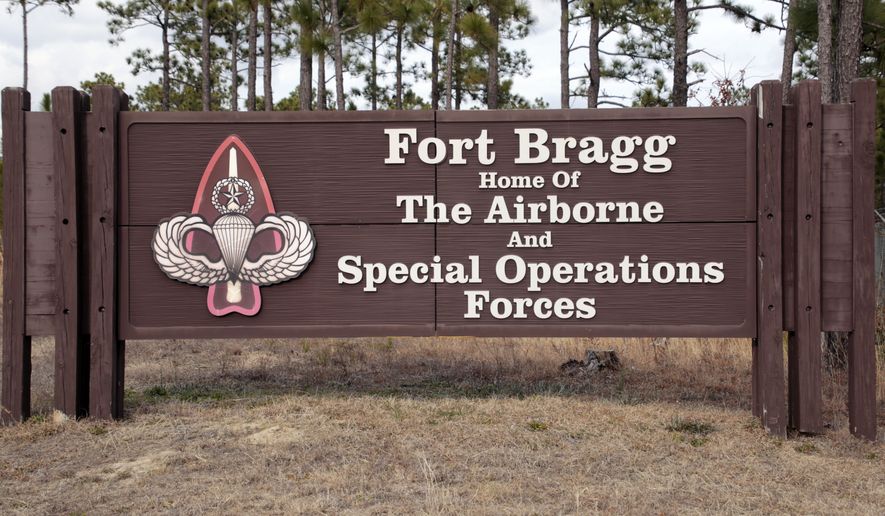

North Carolina’s storied Fort Bragg Army base should be renamed “Fort Liberty,” a congressional commission recommended Tuesday in a significant step forward for the Pentagon’s two-year push to purge from the U.S. military any links to the Confederacy and its most high-profile generals.

The commission, which has its roots in the months of nationwide racial unrest stemming from the May 2020 death of George Floyd, said eight other Army installations tied to Confederate leaders also should be given new names. Well-known installations such as Georgia’s Fort Benning and Texas’ Fort Hood, named after Confederate Gens. Henry Lewis Benning and John Bell Hood, should be renamed, the panel said.

Fort Hood should become Fort Cavazos, after Gen. Richard Cavazos, the Army’s first Hispanic four-star general, according to the panel, which recommended that Fort Benning become Fort Moore to honor Army Lt. Gen. Hal Moore, who was played by Mel Gibson in the Vietnam War movie “We Were Soldiers.”

Fort Liberty, meanwhile, would replace Fort Bragg, named after Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg.

The recommendations Tuesday from the congressional panel, commonly known as the Naming Commission, are not final. The commission will submit a report to Congress by Oct. 1, with final approval by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin.

Federal law requires that the names be changed by Jan. 1, 2024, but the new monikers could be implemented earlier. The issue is seen to be a top priority for Mr. Austin, the nation’s first Black military chief, who has made racial justice and anti-extremism central pieces of his agenda.

“Today’s announcement highlights the commission’s efforts to propose nine new installation names that reflect the courage, values, sacrifices and diversity of our military men and women,” Mr. Austin said in a statement. “I thank the members of the commission for their important, collaborative work with base commanders, local community leaders, soldiers, and military families. And I look forward to seeing their complete report later this year.”

Commission members visited the nine installations last year for “listening sessions” with military commanders and community leaders. They received more than 34,000 submissions related to the renamings, officials said.

“This was an exhaustive process that entailed hundreds of hours of research, community engagement and internal deliberations,” retired Navy Adm. Michelle Howard, the chair of the Naming Commission, said in a statement. “This recommendation list includes American heroes whose stories deserve to be told and remembered; people who fought and sacrificed greatly on behalf of our nation.”

Advocacy groups and critics have argued for years that the military should sever its ties to the Confederacy. The issue came to the forefront in the summer of 2020, in the immediate aftermath of the death of George Floyd, a Black man, during his arrest by Minnesota police. Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was convicted of murder.

That incident, and the racial justice protests that followed, seemed to spark a rapid shift in attitudes at the highest levels of the U.S. military. In July 2020 testimony before Congress, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark A. Milley offered a blunt take on why soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines would be deeply offended by the names Fort Bragg, Fort Hood or other installations honoring Confederates.

“In the Army, for example … we’re up to 20-plus percent African American, and in some units, you’ll see 30%. And for those young soldiers who go on to a base, a Fort Hood or a Fort Bragg or wherever, named after a Confederate general, they can be reminded that general fought for an institution of slavery that may have enslaved one of their ancestors,” Gen. Milley said.

“The Confederacy, the American Civil War, was fought, and it was an act of rebellion,” he said. “It was an act of treason at the time against the Union, against the Stars and Stripes, against the U.S. Constitution. Those officers turned their back on their oath.”

President Trump vehemently opposed the effort to rename bases, arguing that it was designed to erase U.S. history. In June 2020, Mr. Trump said in a Twitter post that his administration “will not even consider” renaming the installations.

He stood by that position for the remainder of his presidency and even vetoed National Defense Authorization Act legislation that required the names to be changed.

Congress overrode the veto, signaling bipartisan support for the effort and formally establishing the panel that made Tuesday’s recommendations.

The recommendations are hardly the end of the story. Some lawmakers seem dissatisfied with the suggested name changes and say the Pentagon can and must go further.

“I’m grateful to the Naming Commission for their recommendation to rename Fort Hood for Richard Cavazos & I urge them to continue honoring the heroism of Hispanic service members by renaming Fort Bragg for Roy Benavidez, a profoundly brave soldier whose legacy deserves to live on,” Rep. Joaquin Castro, Texas Democrat, said in a Twitter post Tuesday.

In addition to Forts Benning, Bragg and Hood, the commission’s other recommendations include:

• Georgia’s Fort Gordon should be renamed after World War II-era Army Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who became the nation’s 34th president.

• Fort A.P. Hill in Virginia should become Fort Walker, after Dr. Mary Walker, a civilian surgeon in the Civil War who received the Medal of Honor.

• Fort Polk in Louisiana should be renamed Fort Johnson, in honor of Henry Johnson, who served in World War I and was awarded the Medal of Honor.

• Virginia’s Fort Lee should become Fort Gregg-Adams, after Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams.

• Virginia’s Fort Pickett should be renamed Fort Barfoot, after Tech. Sgt. Van T. Barfoot.

• Fort Rucker in Alabama should be renamed Fort Novosel, after Chief Warrant Officer 4 Michael J. Novosel Sr.

• Mike Glenn can be reached at mglenn@washingtontimes.com.

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.