The Washington Times was conceived as a strongly visual paper for a strongly visual world. For 40 years, that sensibility has not wavered. As the work on this page attests, The Times’ commitment to visual excellence has provided a platform for the talents of some very gifted editorial artists. Their funny little pictures are often worth much more than a mere thousand words.

Editorial cartoons were movies in the papers before there were movies in the theaters. Even today, an editorial cartoon plays in the readers’ minds with an artist-provided image and a reader-provided soundtrack. “Them damned pictures,” as Boss Tweed called Thomas Nast’s offerings in the 1870s, have provided humorous, edgy, irreverent, often outrageously offensive windows on issues great and small for nearly two centuries, delivering an instantaneous, visceral punch through the newspaper readers’ eyeballs. It’s at its best expressing a public mood, a cultural ripple, visually taking the pulse of the American moment.

A good one can’t be unseen: The copperhead press’ portrayal of Abraham Lincoln as a 6-foot-3 glowering, gangly ape; Nast’s pear-shaped Boss Tweed in prison stripes; David Low’s resolute Churchill; Herblock’s frantic man shouting “Fire!” up a ladder to quench Liberty’s torch with a bucket of hysteria; Bill Mauldin’s statue of Lincoln grieving the death of John F. Kennedy; Pat Oliphant’s Lyndon Johnson hanging a “Soul Brother” sign on the White House gate; Paul Conrad’s relentless Nixon tapes indictments, etched in every imaginable permutation.

Some folks say the first American political cartoon was Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” snake, a drawing that succinctly summed up the revolutionary cause in 1775. The proud tradition of graphically making friends, outraging readers and influencing people with inky scratchings has gone on, with varying degrees of success, ever since.

Well-executed editorial cartooning marries ideas and pictures seamlessly, frequently with an emotional impact that words and photos alone do not equal. Where language and photography in a newspaper are traditionally employed to bring facts to the reader concerning the day’s events, political cartoons serve to bring insight, attitude and perspective. The aim of a political cartoonist is to evoke in the audience “how” to feel and think about an issue, memorably expressing not only the artist’s point of view but also that of the organization that publishes the work. A well-done cartoon can arm the reader with a clever opinion or joke. Back in the old days, when papers wore their publishers’ opinions on their sleeves, editorial cartoons were often displayed on the front pages as heavy artillery in the arsenal of crusading editors.

To The Washington Times at its 1982 debut, the bad guys and good guy on the global scene were clearly defined: Soviet communism and its American nemesis, President Reagan. Additionally, another American political revolution of sorts was in the making: The disco era was dead, replaced with 1980s hair and fashion. In short, the world presented what political cartoonists refer to as a “target-rich environment.”

SPECIAL COVERAGE: Freedom, family, faith: Celebrating 40 years of The Washington Times

Gib Crockett, revered star of the recently closed Washington Star, was given the honor of producing the first Washington Times editorial cartoon, published on May 17. The stalwart David Seavey took the wheel from there and stolidly carried the cartoon torch for the paper’s first year.

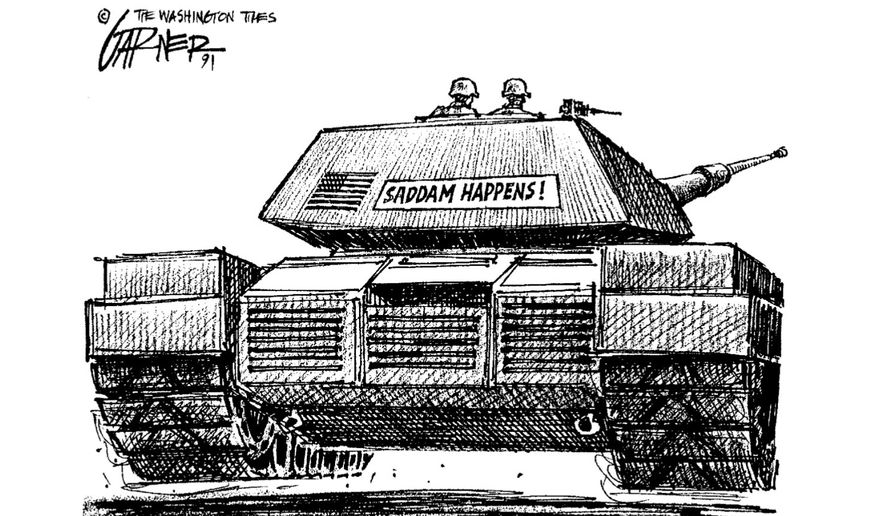

Subsequently, the quietly gifted, award-winning Bill Garner was coaxed back from the Memphis Commercial Appeal to bring his sharp, witty line, enormous artistry and plain-spoken decency to the post of The Times’ editorial cartoonist, a position he proudly occupied for the next three decades. His “Saddam Happens” bumper sticker on the back of an Abrams tank, his portrayal of the Clintons as “Bonny and Clod,” his brilliant, economical caricatures, and so much else caught the spirit of the age viewed from a ground-zero Washington seat.

During those early days, Managing Editor Smith Hempstone recruited the sophisticated contributions of Peter Steiner, whose facile draftsmanship had graced the pages of The New Yorker. Mr. Steiner’s sometimes cold-eyed single-panel pronouncements on social foibles graced The Times’ pages for decades as well.

For some years, a varied stable of syndicated cartoonists with a conservative political bent filled the vacuum left by Mr. Garner’s retirement. Most recently, the cartoon lucubrations of Alexander Hunter, whose journeyman (though award-winning) work falls somewhere between Thomas Paine and Jay Ward, have occupied the space opposite each day’s editorial.

The Times hopes its readers will enjoy these selected hand-drawn glimpses of history, which are but the tip of a much larger, four-decade-sized iceberg of insightful artistry.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.