OPINION:

Editor’s note: This is one in a series examining the Constitution and Federalist Papers in today’s America.

In considering the Constitution, it is essential to remember that there were two factions involved in the discussion — the Federalists, who prioritized liberalism, and Anti-Federalists, who prioritized democracy — and one dead French aristocrat and political philosopher who helped them both find their way.

One should not freight the term “liberalism” with a 21st-century connotation. During the Age of Enlightenment, particularly within 18th-century America, liberalism carried multiple definitions dependent upon the interpreter. In this setting, “liberalism” means simply a system of government that protects the rights of the individual. Democracy, supported by the Anti-Federalists, is fairly self-explanatory.

The question with which the Framers grappled was how to create a system of government balancing democracy and liberalism.

The question is more complicated than it initially appears. In ancient Greece, particularly Athens, there was plenty of democracy, but no liberalism. One need only reference Socrates and his ultimate demise as evidence of that. In Great Britain, liberalism wholeheartedly existed, but there was a deficiency of democracy.

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists both agreed the answer was federalism: a system of government where powers are divided among a national, centralized government and regional, state governments. Do not mistake the term “Anti-Federalist” as being anti-federalism; this is an unfortunate misconception. The Anti-Federalists merely disagreed with the Federalist plan on the type of federalism initially suggested at the Constitutional Convention.

Anti-Federalists believed that democracy could exist only on a small scale. Thinking about Plutarch’s Athens, or Rousseau’s Geneva, one finds validity in that belief.

For this reason, Anti-Federalists were vocally opposed to Federalist assertion of the necessity of “extending” the democratic sphere. The Anti-Federalists believed that the extension of a pure democracy eventually would give rise to a tyrannical, centralized government — whether formulated in a despotic executive or an overly powerful legislature.

For their part, Federalists believed that democratic institutions, organized on a local spectrum, would lead to a nation divided: my country Virginia, my country Massachusetts, etc. Consequently, they favored a centralized government that would be the glue holding the smaller, democratic institutions of the states together as a unified nation.

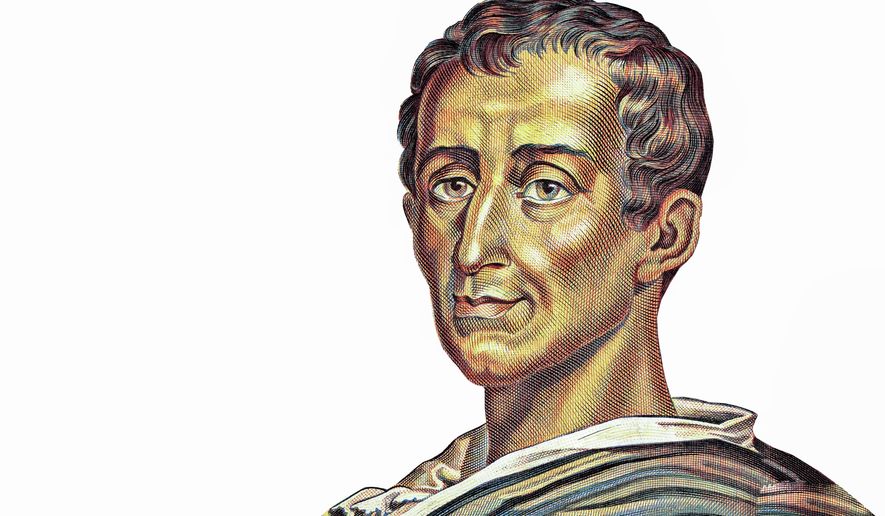

Enter Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu — a French aristocrat who had died in 1755 — and his political treatise “The Spirit of the Laws.”

The Anti-Federalists admired Montesquieu and referenced Books (chapters) I-IX as the basis of their ideas about the primacy of democracy. The Federalists admired him as well and focused on Book XI as their guide with respect to liberalism and creating durable institutions that protect political liberty.

Influenced by Montesquieu, James Madison and the Framers created the first layer of separation of powers: federalism. The centralized government would act to hold the union together and protect individual liberties while not overly infringing upon the rights and authorities of the individual states.

It is federalism that provides the balance, that protects individual liberty while representative democracy administratively and more efficiently operates on a smaller scale within the states. The Federalists acknowledged that each state personifies different cultures — and that was to be respected. The responsibility of the federal government was to protect an individual’s right to privacy and property — not create a national culture, dialogue, etc. That responsibility was given to the states.

Montesquieu was not done contributing to the young republic yet. In addition to separating powers between levels of government, he advocated separating powers within levels of government.

Madison and the Framers ultimately wanted to construct a federalism in which the national government would not become tyrannical upon the states and in which the whims and emotions of those represented within the smaller democracies of the states would not result in an overly tyrannical federal government. Consequently, they also adopted Montesquieu’s idea of separation of the powers within the national government.

The political authority of the federal government is divided into the legislative (Article I), executive (Article II) and judicial (Article III) branches of government. Montesquieu proposed that these branches should be separate and independent from the others to effectively and efficiently defend the liberty of the body politic.

Furthermore, and solely through separation of powers, checks and balances find their port of origin. The separate, independent branches perform checks on the others to ensure, again, one does not become tyrannical.

Madison explains in Federalist 48: “It will not be denied, that power is of an encroaching nature, and that it ought to be effectually restrained from passing the limits assigned to it. After discriminating, therefore, in theory, the several classes of power, as they may in their nature be legislative, executive or judiciary, the next and most difficult task is to provide some practical security for each, against the invasion of the others.”

Without Montesquieu’s ideas on how democracy can be protected by federalism and tyranny checked by separation of powers within a national government, it is entirely possible that the Federalists and Anti-Federalists may not have been able to bridge their substantial differences and create our national Constitution.

• Aaron S. Van Allen is an adjunct professor of Government at Liberty University.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.