OPINION:

Would you take a college seriously if some geography department professors argue that the world was flat, or a medical school where some professors argue that the way to cure “a fever” is to bleed the patient (as was done to George Washington)?

Yet, we have a world in which many colleges have so-called professors of economics who argue for socialism, price controls or for virtually unlimited government spending, government-created money or no limits to tax rates. If their ideas were merely contained in the academy, it would not be so bad; instead, they are taken seriously by the ignorant in the media and the political establishment.

Before 1776, there were no people who referred to themselves as economists, nor was there an academic field known as economics — even though now it is one of the most popular college majors. Despite its recent vintage, the field of economics has a widely agreed-on founding father — Adam Smith (1723-1790) — who was a professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Up to the 1700s, per capita incomes had barely changed from the time of recorded history; and Thomas Hobbes correctly noted the life of man was “solitary, poor, brutish, and short.” The industrial revolution began in England with the invention of the steam engine, which would free mankind from physical drudgery. The evolution of private property rights in England had started with the Magna Carta of 1215, enabling the widespread accumulation of capital and its productive investment. The Scottish Enlightenment was well underway, emphasizing rational thought and personal and economic liberty.

Smith was a key figure of the Enlightenment who was influenced — and vice-versa — by his close and older friend David Hume and by his American contemporary Benjamin Franklin, whom he met during Franklin’s stays in England and France. Despite the immense changes in the economic order, no seminal work had been published on it until Smith’s “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” in March 1776 (246 years ago this month). The amazing thing is Smith was correct in almost all of his observations and policy recommendations, including the importance of free trade and free markets and competition in allowing the common man almost unlimited opportunity for a better life.

In the two and half centuries since “Wealth of Nations,” many others have made worthwhile contributions to economics, while not an insignificant number have been wrong but appealing, causing great misery. Fortunately, Mark Skousen has just published the 4th edition of his great book, “The Making of Modern Economics: The Lives and Ideas of the Great Thinkers.”

Mr. Skousen has produced the single best book on virtually all of those who have had a significant impact on the field of economics — for good or bad — regardless of their political leanings. Despite being an economist with a definite political viewpoint, he treats the many figures he covers with considerable fairness — even the bad actors. Mr. Skousen presents the pros and cons of his subjects’ contributions to the field in a clear, understandable language. He also describes many of their eccentricities, including sex scandals not usually associated with a profession considered dull by those who have only met the run-of-the-mill economist.

Several notable economists like Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929), best known as the author of “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” were totally disagreeable people. Veblen despised both capitalists and Marxists, and most everyone else, and was often slovenly or worse in his appearance — but had the redeeming quality of being highly provocative.

Frederic Bastiat (1801-50) was a French essayist and economist, who is best known for his clever parables destroying economic fallacies, such as the “petition of the candlemakers” and the “broken window theory.” As Bastiat wrote: “There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect, and the good economist takes into account the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.”

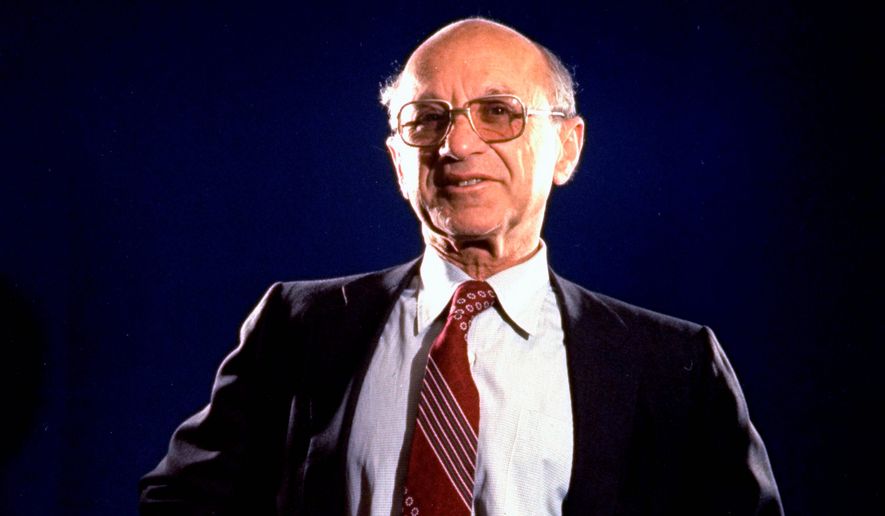

Much of the struggle in economic thought in the 20th century can be understood in the rise of John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) and his disciples, notably Paul Samuelson (1915-2009), and their subsequent fall. This was mirrored by the fall and subsequent rise of F.A. Hayek (1899-1992), an early contemporary of Keynes, and the rise of Milton Friedman (1912-2006), a contemporary of Mr. Samuelson.

Despite their brilliance, neither Keynes nor Samuelson had as good a grasp of the unforeseen as did Hayek and Friedman.

The new 4th edition of Mr. Skousen’s book takes the reader up through the pandemic and the rise of cryptocurrencies. Mr. Skousen is better known as an economic entrepreneur (he is the creator of the annual FreedomFest attended by thousands in Las Vegas), then as an academic, despite having taught at several universities, and is now an adjunct professor at Chapman University. He is also the author of many books, including several textbooks.

Few know who the great economists were and what they contributed. Mr. Skousen has done the world a favor by producing a book that is a delight to read cover-to-cover or as a reference given its detailed source notes.

• Richard W. Rahn is chair of the Institute for Global Economic Growth and MCon LLC.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.