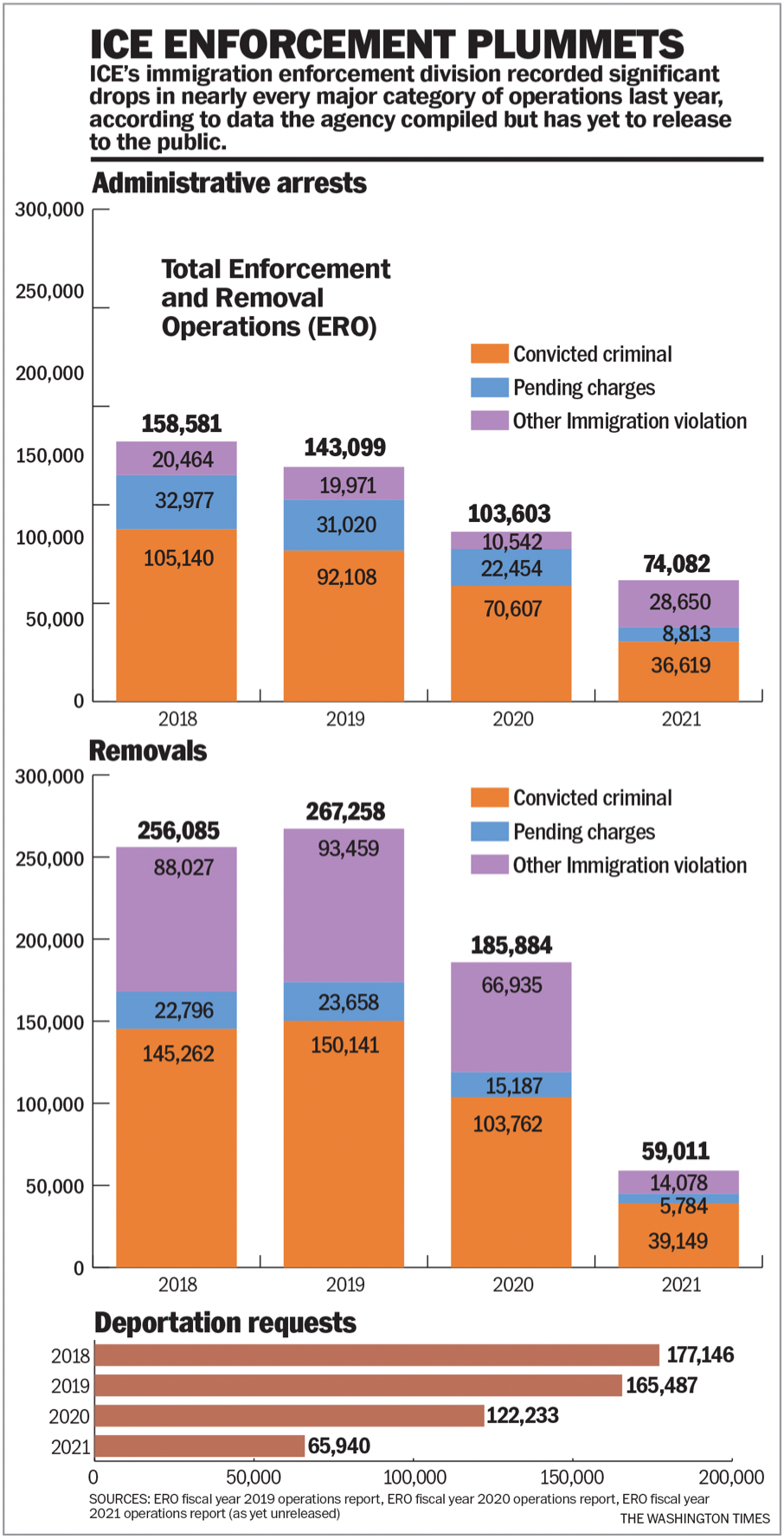

The federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s deportation division arrested 48% fewer convicted criminals, deported 63% fewer criminals and issued 46% fewer “detainer” requests to other law enforcement agencies last year, according to data that ICE officials have tallied but have yet to release to the public.

Yet strangely, arrests of illegal immigrants with no criminal records — whom the administration has generally deemed a lower priority for enforcement — soared 170%, according to the internal ICE numbers.

The numbers, obtained by The Washington Times from a Homeland Security Department source, portray an agency that has ceded much of its traditional role of interior enforcement of immigration laws under President Biden.

Analysts said the drops in arrests and deportations of people with convictions on their records mean tens of thousands more dangerous people are out in American communities far from the southern border.

One ICE officer called the arrest and removal numbers “an acknowledgment that ICE officials are being paid not to do their job.”

The data could also undercut the Biden administration in several court cases where it is arguing that its immigration enforcement priorities are focused less on numbers and more on “quality” arrests in the most serious cases.

“These numbers prove that the administration’s entire enforcement regime is built on a mountain of lies,” said Stephen Miller, President Trump’s former point man on immigration issues and now the president of America First Legal, which is involved in the court challenges. “What this administration has done, as the data prove, is they have voluntarily released, by the tens of thousands, dangerous public safety threats that they have the resources to remove, and that they declined to remove as a discretionary policy choice.”

The Times reached out to ICE, which did not provide a comment for this article.

The unpublished data is from fiscal year 2021 and covers ICE’s enforcement and removal operations division. That’s the branch that scours prisons and jails for deportable migrants, manages more than 3 million cases of people in the country awaiting hearings, handles the detentions of tens of thousands daily and operates the flights that send deportees back home.

According to the data, enforcement and removal operations made 36,619 administrative arrests of convicted criminals last year, down nearly half compared with 2020, when the division nabbed 70,607 convicts. Arrests of those with pending charges fell from 22,454 to 8,813.

Deportations dropped even more. The ICE division recorded the removals of 39,149 convicts in 2021, down 62% from 2020, when 103,762 convicts were ousted, and far below the pre-pandemic rate of 2019, when 150,141 convicts were removed.

“Detainers” — official requests to state and local authorities to cooperate in turning over deportable migrants to ICE — also fell dramatically, from 122,233 in 2020 to 65,940.

The only major category of enforcement that did increase in 2021, according to the data, was arrests of people without convictions or pending criminal charges, or what ICE calls “other immigration violators.” Those are rank-and-file illegal immigrants whom the administration says are usually not a priority unless they are very recent border jumpers.

Arrests of those violators rose from about 10,500 to about 28,700, or more than 170%. They accounted for nearly 40% of all enforcement and removal operations administrative arrests. During the Trump administration, those low-priority arrests represented only about 10% of the total.

Among at-large arrests — the most fraught cases where enforcement and removal officers are in communities rather than scouring prisons and jails — non-criminals were the targets 71% of the time in 2021, compared with less than 30% of the time in the Trump years.

The enforcement and removal operations division produced the data months ago in a full report, just as it has done for previous years, one agency source said.

But the report has been bottled up.

ICE last week released an agencywide summary that included more general arrest and deportation numbers without the criminal breakdowns. The detainer number, included in previous years’ reports, was left out this time.

“The fact that the Biden administration is not publishing these numbers on their own is a very strong sign that the White House knows the impact of their policies is disastrous for ICE’s mission and for public safety,” said Jon Feere, a former chief of staff at ICE in the Trump administration. “They have chosen to allow countless criminal aliens to go free, and they somehow think they can hide this from the public.”

A memo’s impact

Analysts and ICE sources pointed to several explanations for the numbers, including some lingering COVID-19 restrictions on detention capacity and a key court decision governing detention policies.

The biggest factor, the sources said, is the Biden administration’s approach to immigration enforcement. The policy was laid out first in a Feb. 18 ICE memo and then updated in late September by Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas.

ICE officers said that under those policies, they have been told to forgo making arrests in all but the most serious of cases. They also have been told to look for “mitigating” circumstances to try to prove why someone shouldn’t be subject to enforcement action.

The Feb. 18 memo and now the Mayorkas policy have been challenged in court. One case was brought by Texas and Louisiana and another by Arizona, Ohio and Montana. The states say the Biden administration is derelict in its duty to enforce the law.

The Biden administration argues that ICE’s focus is on quality arrests, which it says is more expensive. As long as the number of high-value targets is increasing, the Biden administration says, that’s proof it is enforcing the law.

“We are focusing on sort of those — what we consider quality arrests, the ones that are the most severe threats to our communities,” a top ICE official told reporters last week in defending the numbers. “I think you’ve been able to see that carried out pretty clearly, that we’ve focused down on those public safety threats.”

He pointed to aggravated felon arrests as proof of more high-value targets. In 2021, ICE says, it made 12,025 administrative arrests of people with aggravated felony convictions. That was nearly double the 6,815 ICE said it tallied in 2020.

“ERO did a magnificent job of having arrests for an average of about 1,034 aggravated felonies per month, for between February and September in the administration,” the official said. “That’s about a 53% increase of the monthly average for that year over the Obama years and a 51% increase over the monthly average in the Trump years.”

Multiple sources at ICE said those numbers are misleading.

Officers previously didn’t bother characterizing many arrests as aggravated felons because there was no reason to. Under the Obama and Trump administrations, they could make arrests without having to cross that threshold.

That means the comparison ICE is touting is invalid, officers said. There are likely many aggravated felons who were arrested but don’t show up as such in the earlier data.

To boost the aggravated felon numbers after Mr. Biden took office, officials at ICE headquarters regularly prodded field offices to go back and scour their data for aggravated felon cases they may have missed in 2021.

“That’s not good data. It’s not reliable,” one agency source said. “I can tell you definitively there were more aggravated felony arrests in 2020.” Another ICE source called the arrest data “a shell game with numbers.”

A third ICE source said officers are being pushed to ignore information in case files to avoid making arrests, such as instances where someone is charged with a horrible crime but a victim won’t testify, so a lesser charge is lodged.

“The data isn’t often reflective of what we do,” that source said. “If you let us do our jobs the way we used to, we’re going to get quality arrests and then some.”

Instead, the source said, field office supervisors are rejecting cases that aren’t flashy enough — even cases that would seem to fit under Mr. Mayorkas’ priorities — with an eye to keeping numbers low.

“It’s like telling the highway patrol you can only arrest drunk drivers on a Tuesday if they’re driving a blue F-150 in the right lane,” the source said.

Critics also question data showing a drop in arrests associated with specific serious criminal offenses.

According to the report ICE released last week, the agency tallied 1,506 arrests with homicide-related offenses. That was down from 1,837 in 2020. Kidnapping-related arrests fell from 1,637 in 2020 to 1,063 last year. Assault-related arrests fell from 37,247 in 2020 to 19,549 last year. Sexual-assault-related arrests dropped from 4,385 to 3,415.

It’s difficult to square those changes with the claim of higher aggravated felon arrests, skeptics say. ICE did not respond to an inquiry on that discrepancy.

Congress and judges

Mr. Feere, now director of investigations at the Center for Immigration Studies, said members of Congress should demand to see the full enforcement and removal operations report.

Mr. Miller, an architect of the Trump administration’s immigration policies, said judges hearing the legal challenges could also demand the full report.

“These numbers show [the Biden administration’s] entire stated rationale for substantially curtailing ICE enforcement is predicated on a complete falsehood,” he said. “Far from prioritizing the removal of public safety threats, they are achieving their drastic reduction in removals by freeing public safety threats into the United States.”

He also challenged ICE’s argument that it is spending its limited resources more carefully.

“ICE has the capacity to remove every single criminal alien referred by a local jurisdiction, every single year, at current funding levels,” Mr. Miller said. “What this administration has done, as the data proves, is they have voluntarily released, by the tens of thousands, dangerous public safety threats that they have the resources to remove.”

The enforcement and removal operations division’s budget has hovered between $4.1 billion and $4.3 billion for the past several years.

In 2021, it completed 199,033 total arrests, removals and detainer requests, or about $21,700 per enforcement action.

In 2020, amid the worst of the pandemic, each enforcement action cost about $10,800. In 2019, pre-pandemic, each enforcement action cost just $7,400 — a third of what the agency spent last year.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the number of ICE arrests in 2021 involving sexual assaults.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.