OPINION:

Last week the Supreme Court of the United States handed Americans an important victory for religious freedom. In the case of Carson v. Makin, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that “to exclude religious persons from the enjoyment of public benefits on the basis of their anticipated religious use of [those] benefits” is a violation of the First Amendment. “The State’s antiestablishment interest[s],” he said, “do not justify enactments that exclude some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor disagreed. “Today, the court leads us to a place… of [dismantling] the wall of separation between church and state that the Framers fought to build,” she bemoaned.

But what is this “wall” of which Justice Sotomayor morns? Where did it come from? What is its context? And why was it considered important to our nation’s Framers?

Maybe a timeline would be helpful in answering these questions.

In 1776 Thomas Jefferson set the cornerstone for our constitutional republic, and on that stone, carved these words: 1) We are created; 2) We are equal; and 3) We are endowed by God – not government – with certain unalienable rights; and foremost among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Thus, Jefferson unequivocally declared that America’s independence was built upon a “religious” understanding of human origins, priorities, and purpose.

In 1791 James Madison wrote the First Amendment, stating, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” In writing these words, Madison demonstrated two basic things. First, he knew that the pursuit of happiness, i.e., meaning and purpose, was the business of the Church and its parishioners and not the business of the king or the courts. Second, he understood that Congress was the protector of this right and not its progenitor.

Madison’s argument was simple: Government should never presume to define the matters of the Church. Congress has no authority to “establish,” dictate, prescribe, or contradict religious belief. Furthermore, and just as important, Madison makes it clear that no governing body can direct or prohibit how a citizen “expresses” his or her faith. In other words, religion is not merely a secondary matter of one’s private thoughts but rather something that all faithful people live out daily in the market square of life. In summary, the government should leave the Church alone. It should never presume to tell people what to believe or how they can or cannot practice their faith.

Eleven years later, at the front end of his presidency, Mr. Jefferson found it necessary to reassure a small group of Christians at the Danbury Baptist Church that they did not have to fear government intrusion: “I contemplate with (utmost) reverence,” he said, “that act … which declared that [the] legislature should ’make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church and State.”

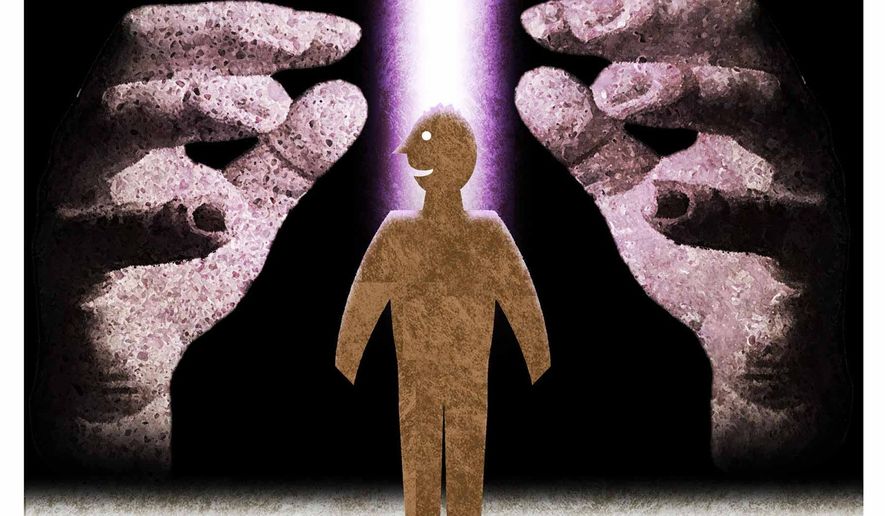

Mr. Jefferson’s message was unmistakable: There is a wall protecting the Church from the State, and no government that is aligned with our Constitution can breach that wall.

However, this wall is not erected as a prison but as a fortress. It exists to protect the Church, not to confine it. Mr. Jefferson no more intended this wall to restrain the Church than he intended the walls of his own home to restrain him. As a house has a door whereby you come and go, buying and selling, engaging culture, and doing your civic duty, so Jefferson’s wall has a door whereby the Church enters society to do its good work. The key here is the Church holds the key, and the door is locked from the inside, not the outside. Mr. Jefferson was clearly telling those concerned in Danbury, Connecticut, that this wall separating the Church from the State was built for the Church’s benefit, not the government’s.

The leaders of our founding era to whom Justice Sotomayor refers never intended our nation to be secular or hostile to religion. In fact, a number of them, in addition to Mr. Jefferson, made this abundantly clear.

John Adams famously said, “Our Constitution is made only for a moral and religious people and is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” In signing the Northwest Ordinance, George Washington stated that “religion and morality” are “necessary to good government.” James McHenry wrote, “The holy Scriptures… can alone secure to society, order and peace, and to our courts of justice and constitutions of government, purity, stability, and usefulness.” Alexis de Tocqueville later concurred, “Liberty cannot be established without morality, nor morality without faith.”

Maybe the good Justice Sotomayor would do well to refresh her reading of the Framers she now presumes to extoll. The list of those who understood that the primary guardian of our constitutional freedoms is the wall of our Biblical faith is nearly endless.

• Everett Piper (dreverettpiper.com, @dreverettpiper), a columnist for The Washington Times, is a former university president and radio host. He is the author of “Not a Daycare: The Devastating Consequences of Abandoning Truth” (Regnery).

Please read our comment policy before commenting.