OPINION:

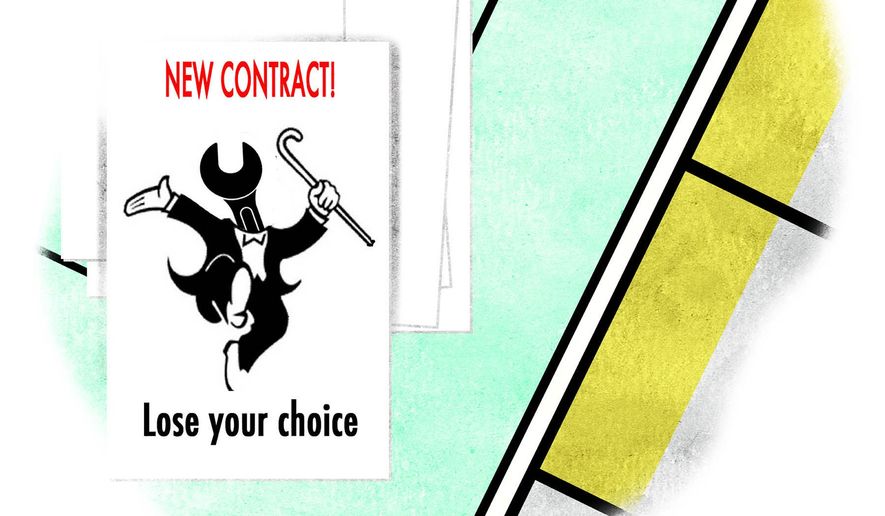

When union officials take control of a workplace, they get a legal monopoly over all contract bargaining and can negotiate the terms of employment for every worker, even those who object. Monopoly bargaining is an extraordinary government-granted power that Big Labor protects at all costs.

Union officials insist that if they have the theoretical support of a majority of workers, all other workers must have union “representation” imposed on them. At its core, forced unionism is contrary to the constitutional principle of free association, and denies workers the right to choose their own representative. But there’s another problem: Union officials don’t even need majority support to get or stay in power.

If union officials win a unionization vote by a “majority” of those voting in a low-turnout election, the law allows them to obtain monopoly bargaining privileges. Once installed, a union doesn’t go away unless it leaves voluntarily, the company closes, or workers remove the union by organizing a decertification vote, which requires navigating a labyrinth of arcane labor laws.

As workers come and go, the forced representation remains. An analysis of over 40 years of union elections found that 94% of workers under union monopolies had never even voted for the union that “represents” them.

Union officials treat workers’ support as an annoying legal requirement, not as something that gives legitimacy to their monopoly power. It’s a mindset shared by many union partisans at the National Labor Relations Board. The NLRB is supposed to neutrally resolve disputes between workers, employers and union officials. Instead, the NLRB uses its power to help union officials maintain their monopolies, and the current Biden majority has been more aggressive than ever.

Examples are everywhere. The NLRB created onerous restrictions on union decertification elections that make it harder for workers to remove an unwanted union. The NLRB’s Biden-appointed General Counsel has even moved to empower unions to gain monopoly bargaining authority without having to hold a secret-ballot election.

Then, there’s the board’s heavy use of mail-in ballots. In-person elections used to be the norm because they allowed NLRB observers to monitor voting and prevent interference. During the pandemic, the NLRB mainly used mail-only voting and has continued to do so even as workers have fully returned to work, mostly because union officials have demanded it.

A recent Bloomberg Law analysis demonstrated that unions are more likely to win elections when turnout is lower, so union officials benefit from making it harder to vote. By forcing workers to mail in their ballots from home — instead of giving them an opportunity to stop by a workplace voting booth — the NLRB further tilts the playing field in union officials’ favor by driving down turnout. And, because federal law lets union agents, but not employer representatives, visit workers in their homes, mail voting opens the door to one-sided union interference that’s impossible for election observers to monitor.

Mail-in voting has other deficiencies. Post office delays are all but inevitable. When workers have asked the NLRB for an in-person election, citing concerns that post office delays could result in votes not being counted, the NLRB has countered that either side is “free to present evidence of any disenfranchisement of voters, if applicable, in post-election objections,” only to reject obvious evidence of disenfranchisement when it occurs.

When post office delays resulted in only three of ten ballots arriving on time during a unionization vote at CenTrio Energy, the NLRB said that was no problem, and certified a 2-1 election victory for union officials. Of the seven ballots that arrived late, six arrived just two days after the Nov. 4 deadline, with postmarks ranging from Oct. 15-25, meaning all six were mailed with more than a week to go in the election.

The NLRB could have directed that the extra ballots be counted since the delays were out of the workers’ control, but it refused. One wonders how the board would have ruled had the initial three votes gone against the union.

But even if the union had won with more votes counted, should the workers who voted “no” really be forced to accept the so-called “representation” of an organization they reject? Union-negotiated contracts frequently harm the interests of many workers, and union officials use their imprimatur as the workers’ “representative” to engage in lobbying and political advocacy that workers may disagree with.

Unionization should be a voluntary choice, not a government-imposed monopoly, and the NLRB shouldn’t heed union officials’ calls to further remove workers’ voices from the process.

• Mark Mix is president of the National Right to Work Foundation.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.