OPINION:

Editor’s note: This is one in a series examining the Constitution and Federalist Papers in today’s America. Click HERE to read the series.

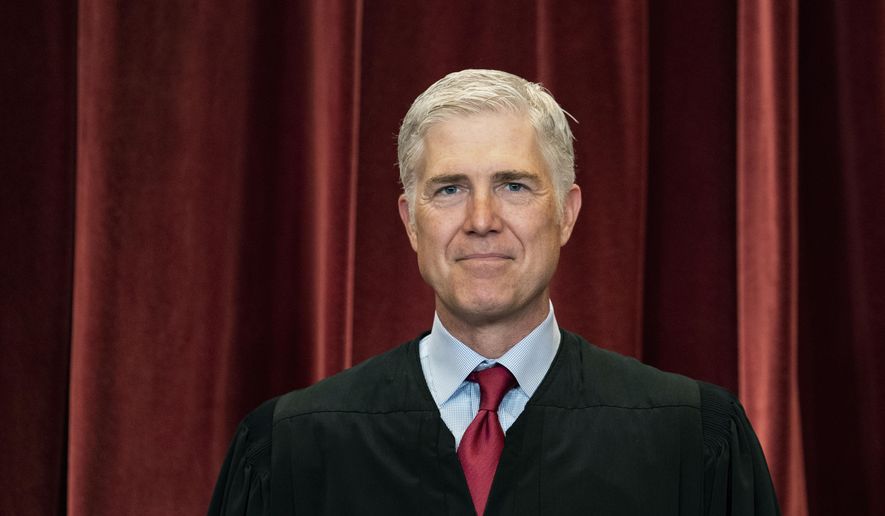

Given the constitutional significance of the Supreme Court’s decision last month in West Virginia v. EPA, in which the high court reasserted the essential nature of the government’s separation of powers, it is worth sharing the remarkable clarity of Justice Neil M. Gorsuch’s concurrence.

Below are the highlights of that concurrence.

“The major questions doctrine works … to protect the Constitution’s separation of powers. In Article I, the People vested [a]ll federal ‘legislative powers … in Congress.’ As Chief Justice Marshall put it, this means that ‘important subjects … must be entirely regulated by the legislature itself,’ even if Congress may leave the Executive ‘to act under such general provisions to fill up the details.’”

“The Constitution’s rule vesting federal legislative power in Congress is ‘vital to the integrity and maintenance of the system of government ordained by the Constitution. … It is vital because the framers believed that a republic … would be more likely to enact just laws than a regime administered by a ruling class of largely unaccountable ‘ministers’ [Federalist No. 11].”

“The Constitution sought to ensure ‘not only that all power [w]ould be derived from the people,’ but also ‘that those [e]ntrusted with it should be kept in dependence on the people’ [Federalist No. 37].”

“The Constitution, too, placed its trust not in the hands of ‘a few, but [in] a number of hands,’ so that those who make our laws would better reflect the diversity of the people they represent and have an ‘immediate dependence on, and an intimate sympathy with, the people’ [Federalist No. 52]. Today, some might describe the Constitution as having designed the federal lawmaking process to capture the wisdom of the masses.”

“Admittedly, lawmaking under our Constitution can be difficult. … The framers believed that the power to make new laws regulating private conduct was a grave one that could, if not properly checked, pose a serious threat to individual liberty [Federalist No. 48]. As a result, the framers deliberately sought to make lawmaking difficult by insisting that two houses of Congress must agree to any new law and the President must concur or a legislative supermajority must override his veto.”

“By effectively requiring a broad consensus to pass legislation, the Constitution sought to ensure that any new laws would enjoy wide social acceptance, profit from input by an array of different perspectives during their consideration, and thanks to all this prove stable over time [Federalist No. 10].”

“The need for compromise inherent in this design also sought to protect minorities by ensuring that their votes would often decide the fate of proposed legislation — allowing them to wield real power alongside the majority [Federalist No. 51]. The difficulty of legislating at the federal level aimed as well to preserve room for lawmaking ‘by governments more local and more accountable than a distant federal’ authority. …”

“Permitting Congress to divest its legislative power to the Executive Branch would ‘dash [this] whole scheme.’ Legislation would risk becoming nothing more than the will of the current President, or, worse yet, the will of unelected officials barely responsive to him. In a world like that, agencies could churn out new laws more or less at whim. Intrusions on liberty would not be difficult and rare, but easy and profuse [Federalist No. 47]. Stability would be lost, with vast numbers of laws changing with every new presidential administration. Rather than embody a wide social consensus and input from minority voices, laws would more often bear the support only of the party currently in power. Powerful special interests … would flourish. …”

“The Court has applied the major questions doctrine … to ensure that the government does ’not inadvertently cross constitutional lines.’ At stake [are] basic questions about self-government, equality, fair notice, federalism and the separation of powers. The major questions doctrine seeks to protect against unintentional, oblique or otherwise unlikely intrusions on these interests. The doctrine does so by ensuring that, when agencies seek to resolve major questions, they at least act with clear congressional authorization and do not exploit some gap, ambiguity or doubtful expression in Congress’s statutes to assume responsibilities far beyond those the people’s representatives actually conferred on them.”

• Michael McKenna is the president of MWR Strategies. He was most recently a deputy assistant to the president and deputy director of the Office of Legislative Affairs at the White House.

• Michael McKenna can be reached at mmckenna@aol.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.