OPINION:

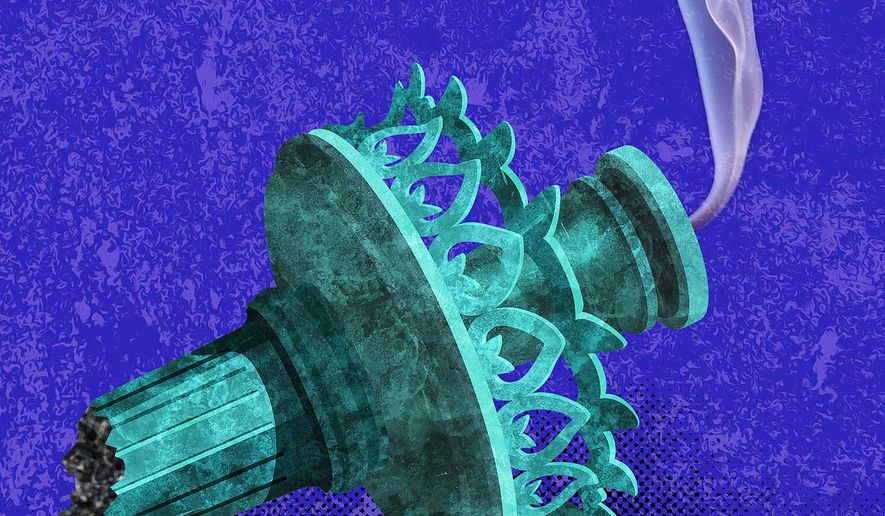

During the past 18 months, the relationship of the American people to the government has changed radically, as the Constitution’s failure to restrain the federal and state governments and protect personal liberty has become manifest.

We know that for the past 100 years, the growth of the federal government has been exponential. And we know that while formally the Constitution still exists, functionally, it has failed miserably, as the deterioration of personal liberty since the spring of 2020 has been as grave as the losses of freedom in the past 100 years.

I am using 100 years as a benchmark because it marks the completion of the federal government’s takeover by the Theodore Roosevelt Republicans and the Woodrow Wilson Democrats, who collectively comprised the Progressive movement.

In a short 15 years, this movement brought us the useless World War I, the destructive popular election of senators, the corrupt Federal Reserve, the theft of property called the income tax and the unconstitutional administrative state.

The war killed millions for naught. The popular election of senators undermined state sovereignty. The Federal Reserve destroyed economic freedom. The federal income tax legalized theft. And the administrative state created an unconstitutional fourth branch of government, “experts” answerable to no one.

Yet the iron fist of totalitarian government visited upon the American people in the name of COVID-19 has struck at the heart of the Constitution and landed heavy blows on average Americans in far more acute and direct ways.

Here is the backstory.

When Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence in 1776 that our rights come from God via our humanity, he and his colleagues set the 13 colonies on a path toward a limited government based upon the consent of the governed. The Declaration proclaimed that the sole moral function of government is to protect life, liberty and property.

In 1776, the colonial governments here consisted of governors appointed by the British king and popularly elected legislatures chosen by the adult, white, land-owning males who bothered to vote.

I say “bothered to vote” because the colonists knew that their legislatures were largely subject to the governors. The same colonists who supported the idea of secession hated the colonial governors as they more frequently than not bypassed the legislatures and issued edicts that they then enforced as if they were laws.

The practice of issuing gubernatorial edicts became so unpopular that 10 of the 13 colonies amended their constitutions in 1776 and 1777 to define more precisely the principle of the separation of powers. The history of the revolutionary period reflects two wars: a war of violence against the king’s soldiers and a war of ideas to persuade reluctant colonists of the value of personal liberty.

The principal instrument of the war of ideas, and the one that James Madison embedded into the Constitution in 1787, was the separation of powers.

The separation of powers, which the late Justice Antonin Scalia called the backbone of the American Constitution, mandates that only the legislature can write laws, only the executive can enforce them, and only the judiciary can interpret them.

The immediate purpose of the separation is to enable any one of the branches to be a check on the other two so that by tension and even jealousy, no one branch could exceed the powers granted to it by the Constitution.

If the president wrote laws, the courts would invalidate them; if Congress interpreted laws, the president and the courts would ignore it; if the courts hired folks to enforce laws, Congress would not fund their salaries.

The ultimate purpose of the separation is to prevent tyranny and thereby preserve liberty.

To assure that the separation of powers worked at the state level, Madison wrote the Guarantee Clause into the Constitution. The Supreme Court has ruled that it guarantees the same separation of powers in the states as is required of the feds.

Now, back to the horrors of the past 18 months. During that time, hundreds of edicts have been issued by mayors and governors, and a few by former President Donald Trump and President Biden. None has the force of law, and each is a legal nullity for the simple reason that only legislatures can enact standards of behavior that carry punishments for noncompliance, otherwise known as “laws.”

What about the legislature of New York, which gave away some of its powers to the governor? That, too, is unconstitutional, as the Supreme Court has ruled that the branches of government cannot cede away or exchange powers; and when they do so, it is a legal nullity.

I am not surprised when the government thumbs its nose at the Constitution that its agents and officers have sworn to uphold and at the legal theories upon which it is based. After all, the Constitution was written to keep the government off the people’s backs. No wonder the government hates it.

I am surprised — and terrified — when the great mass of people acts as sheep when they reject the values of America’s founding documents, and they ignore the history and courage that has undergirded personal liberty in our once free society.

Let’s get this straight: The executive branch of the federal government and nearly all states has told Americans how to live, dress, work, travel, attend church, run their businesses and control their bodies in defiance of the Constitution; and the people — yearning more for a false sense of security than the reality of freedom — bowed down and said: Yes.

Does the government work for us, or do we work for the government? Do we still have a functional Constitution? Can freedom so bitterly fought for and arduously won be this easily dissipated?

The answers to these questions are too repugnant for this American who weeps for liberty to articulate.

For more information, visit The Washington Times COVID-19 resource page.

• Andrew P. Napolitano is a former professor of law and judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey who has published nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.