This is the second in a six-part series on “two years and counting” for the coronavirus. Click HERE to read the series.

The federal government’s compensation fund for people who say they have been injured by a COVID-19 vaccine lists more than 5,600 claims, including body aches, migraines, heart failure and stroke.

More than 100 claims connect deaths to vaccination.

The fund doesn’t report any claims of implanted microchips or rewritten DNA, two of the outlandish theories that have circulated about the mRNA vaccines that were rushed to market to tame the spread of COVID-19.

More than a half-billion doses of Pfizer-BioNtech’s or Moderna’s mRNA-based vaccines have been shot into Americans’ arms.

The efficacy of the vaccines remains heatedly debated, and some people report side effects, but researchers say it’s time to breathe easy over mRNA vaccines on the whole more than a year into history’s most ambitious medical experiment.

DOCUMENT: mRNA COVID-19 vaccines

“MRNA has been around for years and has been given to several hundred million people. If there are going to be any safety problems, they would have declared themselves by now,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

Yet worries about adverse effects have proved tough to shake.

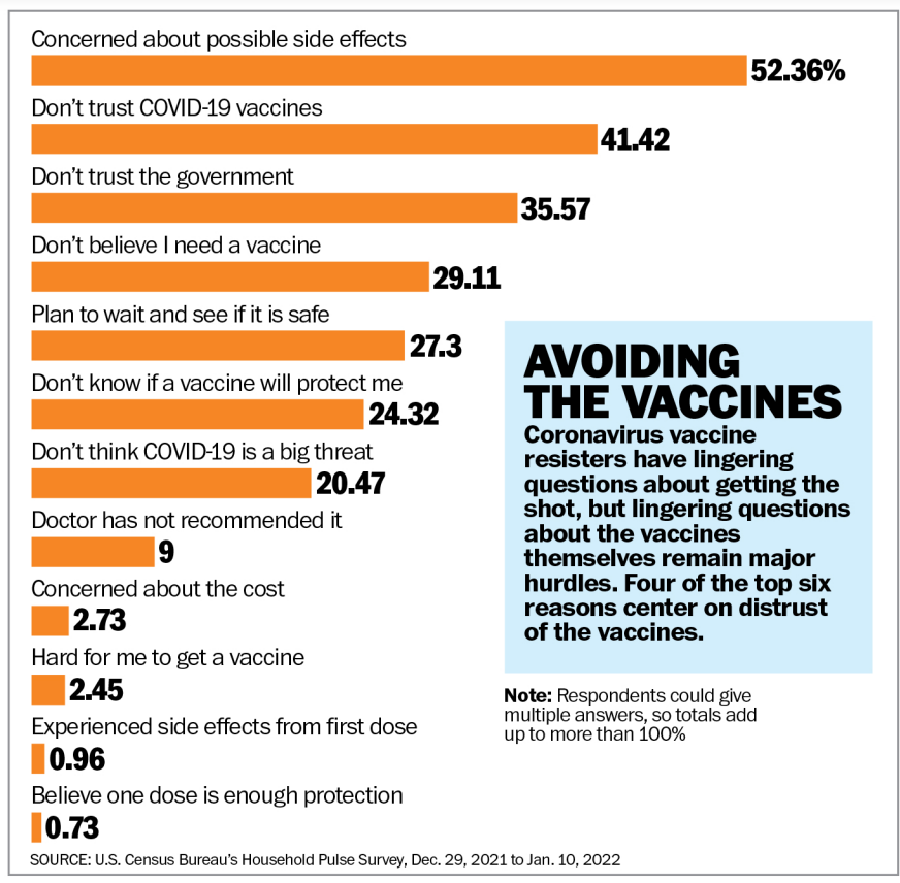

The Census Bureau, which is measuring attitudes about the pandemic and the vaccines as part of its Pulse surveys, found lack of trust in the science and worries about side effects to be the top hurdles. About half of unvaccinated Americans cited potential side effects as a reason they were unlikely to get a shot, and 42% said they “don’t trust the COVID-19 vaccine.”

About 28% said they planned to “wait and see if it is safe,” and 23% questioned the efficacy of the shots. Respondents were able to give more than one answer.

Just 2% worried about cost, 2% said they were having trouble finding the vaccine, 9% said their doctor hadn’t recommended it, 22% thought COVID-19 wasn’t a big deal, 32% doubted they needed a shot and 35% cited a lack of trust in the government.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll taken in December found that 48% of resisters said nothing could persuade them to get a shot.

SEE ALSO: In costliest U.S. fight, little cash goes to actually fight COVID-19

“They largely don’t think the virus poses a great threat. They think the vaccine poses a greater risk,” said Ashley Kirzinger, Kaiser’s associate director of public opinion and survey research.

That argument made its way to the Supreme Court, where justices last month halted President Biden’s vaccine mandate on large businesses.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., one of six justices who joined an opinion blocking the mandate, said during oral arguments that it was the first time the Occupational Safety and Health Administration tried to mandate a procedure with known side effects.

From smallpox to routine shots

A few hundred years ago, dried scabs from smallpox patients were inoculated into people to try to stimulate a mild version of the disease. The method usually made them resistant to illness. Perhaps 1 in 50 people inoculated this way ended up with a case of smallpox severe enough to kill them, but that was a far better ratio than the 30% who died from contracting the disease naturally.

Edward Jenner, an English doctor, then figured out that exposing people to cowpox, a much more mild disease, could stave off smallpox. He named the process “vaccination,” after vacca, the Latin word for cow.

Now every child born in the U.S. faces a gamut of immunizations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists more than 20 shots to be delivered in the first 18 months alone. More follow in the years to come, including recommendations for annual flu shots.

For COVID-19, three vaccines have been approved for use in the U.S.

Johnson & Johnson’s version uses a modified and inactive virus to give instructions to cells in the body to stimulate an immune response. The body produces antibodies that are ready to fight off a live coronavirus infection.

Pfizer and Moderna don’t use a virus, but rather a genetic code — messenger ribonucleic acid, or mRNA — to spur cells to create a protein that mimics enough of the coronavirus to stimulate an immune response.

The process has been studied for decades, and mRNA vaccines for other viruses were in development when SARS-CoV-2 first appeared. Scientists scrambled to produce a molecular model for an mRNA vaccine that would work against the novel coronavirus.

A promise of mass purchases of doses from the U.S. government helped Moderna and Pfizer build manufacturing capacity.

Although mRNA had been under research, the speedy deployment of vaccines involving genetic codes triggered a fierce debate over safety.

Some of the claims are outlandish, but worries about the lasting effects of genetic messaging persist. A paper written by Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers arguing that the coronavirus could permanently alter DNA was twisted by skeptics into an argument that the vaccines would permanently alter DNA.

Experts say that’s not possible. The mRNA doesn’t enter the nucleus of a cell, where DNA is stored.

In short, experts approve of more research but say it’s time to start treating mRNA to protect against COVID-19 as just another of the dozens of shots Americans are supposed to get throughout their lives, beginning with a hepatitis B shot administered hours after birth.

Claims against mRNA

The problem is that a large contingent of people aren’t listening to the experts.

When former President Donald Trump announced at an event that he had received a booster shot for the vaccine, some of his supporters booed him.

Vaccine resisters have focused on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System for evidence of problems with the shots. VAERS has been operating since 1990 and has about 1.7 million incidents reported. Half of them have come in the past year and are related to COVID-19.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, an outspoken Republican from Georgia, was banned from Twitter for reporting false information after she pointed to VAERS as evidence of “extremely high amounts of Covid vaccine deaths.”

VAERS is a clearinghouse for people to report their own experiences, and it’s not proof of a causal relationship. Some researchers say that with so much attention on the coronavirus and the vaccines, it’s not surprising that people are reporting everything they’re feeling.

“Anybody can report whatever they want in VAERS,” said Gabe Kelen, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “There are reports in there about dogs dying — like after someone got a vaccine, their dog died.”

Other researchers put more stock in the system.

“Every single VAERS report is a red flag,” said Linda Simoni-Wastila, vice chairwoman of the Department of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Aditi Bhargava at the University of California, San Francisco, said VAERS might be underselling the incidence rate of side effects.

“People were conditioned to believe that the vaccines were safe and some adverse events were expected. So most didn’t report it because it was all part of the package,” she said.

Others may not talk about their symptoms out of fear of being labeled anti-vaccine, she said.

A more robust set of data is the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program, run by the federal Health Resources & Services Administration. Since 2010, the CICP has acted as a payer of last resort, covering health-related losses such as medical expenses or time off work that no other party is in a position to compensate.

As of Dec. 1, CICP listed 5,630 active claims stemming from treatments for COVID-19, including 2,969 claims of injury or death from a vaccine. The system does not break down those claims by manufacturer, so it’s impossible to say how many were related to mRNA.

None of the claims has been adjudicated, so each one leaves a question mark about the vaccines.

They include about 120 claims of death, 86 reports of stroke, 16 severe allergic reactions, and dozens of aches, pains, headaches and other mild symptoms.

Researchers last year dived into reports that younger men and teenage boys showed a higher incidence — though still rare — of inflammation of the heart, called myocarditis, after receiving a second dose of an mRNA vaccine.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in October examining the health records of Israel’s largest health care system, Clalit Health Services, found that 10.69 of every 100,000 people ages 16 to 29 had developed the generally temporary heart problem after their second dose of the vaccine.

Of the 2.5 million people of all ages studied, 54 — or 2.13 out of every 100,000 — developed myocarditis.

Of those 54 patients, 51 were male. Forty-one cases were considered mild, 12 intermediate and one severe. Among the patients who developed myocarditis, 69% suffered it after the second dose.

What’s not clear, said Ms. Bhargava, director of laboratory research at the university’s Center for Reproductive Sciences, is whether something in the mRNA vaccine is causing the condition.

She wonders whether mRNA triggers some people to make more of the protein than others and whether that has anything to do with the myocarditis cases. “Different people may be getting different doses,” Ms. Bhargava said.

Even if more incidents are reported on the government database, what’s important is that incidents of myocarditis are rare and the benefits of protection against COVID-19, which can damage the heart, is worth the risk, said Sean O’Leary, vice chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics committee on infectious disease.

None of the children who have developed myocarditis has died, and the chest pain and other frightening symptoms are usually mild and temporary.

Looking beyond COVID-19

Bolstered by their experiences with the coronavirus, mRNA supporters see plenty of other targets for vaccines based on the technology, though it’s not clear when any might be ready.

Pfizer had been working with mRNA to develop a flu vaccine since 2015, well before the coronavirus appeared.

CEO Albert Bourla said at a forum organized by the Atlantic Council, an international affairs think tank, that he was unsure what to think when his researchers initially said they wanted to use the same method to develop a COVID-19 vaccine.

“I knew that there was not a single project with mRNA out there,” he said, but his scientists convinced him the investment was worth it.

Pfizer spokeswoman Jerica Pitts said the company is working on mRNA drugs to combat respiratory diseases other than the flu and to prevent cancer and genetic diseases. She declined to say when the company might seek Food and Drug Administration approval for any of them. “We cannot comment on any outcomes from the study until we have results or speculate on what outcomes there may be,” she said.

Kernal Biologics of Cambridge, Massachusetts, is “fast-tracking” the development of an mRNA cancer drug after its studies showed it could be effective.

Another drug manufacturer trying the method is Germany-based CureVac.

The coronavirus vaccines represent “the tip of the iceberg when it comes to realizing the real-world impact of mRNA treatment,” said Sarah Fakih, a CureVac spokeswoman.

The company is exploring the method to develop treatments for “everything from cancers to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. The potential applications of transformative mRNA technology are vast if you consider how many types of diseases or conditions are linked to proteins,” she said.

Researchers are developing them more slowly than the COVID-19 vaccine because they don’t have the same urgency.

“The sheer amount of funding and urgency behind getting a COVID-19 vaccine to the world helped speed up preclinical and clinical-stage activities as well as the approval process for the licensed mRNA vaccines,” she said. “One of the reasons you don’t see more mRNA products on the market for other indications is simply because they have not had the same kind of backing and accelerated timelines. But now that mRNA is in the spotlight on the world stage, we might expect that to change.”

For more information, visit The Washington Times COVID-19 resource page.

• Kery Murakami can be reached at kmurakami@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.