This is the fifth in a six-part series on “two years and counting” for the coronavirus. Click HERE to read the series.

Americans are eager for a post-omicron lull in the pandemic, but experts warn that the coronavirus isn’t finished.

New variants aside, the pandemic over the past two years has carved scars across society that the country hasn’t begun to face.

“We’re a little bit like that zebra that’s in the jaws of the crocodile and is stunned and limp and doesn’t quite grasp what has happened to it,” said Nicholas Christakis, a doctor and social scientist at Yale University. “People don’t yet fully grasp the magnitude of what has happened to us.”

Some changes are palpable. Nearly 1 million Americans have died from COVID-19, and hundreds of thousands fewer babies have been born during the pandemic. The Census Bureau says the population is growing at the slowest pace since the country’s founding.

The economy has shifted in radical ways, and it’s not clear where it will end up, but millions of people are staying out of the workforce for now.

DOCUMENT: How the coronavirus continues to shape American lives

Some ramifications are less obvious.

In addition to the dead, scientists say millions more survived COVID-19 but developed disabilities such as cardiac problems, damaged lungs or weakened kidneys. Scientific American said medical professionals expect to be dealing with a “tsunami of disability” for years.

Even those who weren’t personally struck by the virus have undergone changes.

Younger children have never had a normal school year. Masks and dividers between desks have robbed them of the kinds of encounters that build resilience, negotiating skills and basic social understanding.

The office watercooler as a kibitzing point is gone, at least for now. Daily run-ins with friends and colleagues have to be scheduled or don’t happen at all. Meetings at coffee shops have been replaced with Zoom sessions.

Social distancing, initially a medical prescription for slowing the spread of COVID-19, has become its own epidemic.

SEE ALSO: COVID-19 vaccines’ flaws dash hopes of reaching herd immunity

“It’s like a new cubicle. Your cubicle now is your house, but nobody’s going to pop over the wall and say, ‘You want to have lunch?’” said Allen Furr, an emeritus professor of sociology, anthropology and social work at Auburn University.

Cleaning up

Dr. Christakis, whose book “Apollo’s Arrow” chronicles the country’s early struggles and successes during the pandemic, figures on three phases. The first stage, when the virus rages, is winding down.

Later this year, he said, the country will enter the intermediate stage with the virus becoming endemic. Most everyone will have contracted COVID-19 or been vaccinated, acquiring some immunity.

Barring a devastating new virus variant that is more deadly or better able to evade vaccines, COVID-19 will become “a background killer” like the flu. U.S. deaths from COVID-19 will drop from about 2,500 a day to an average of 50 to 100 — about the same as the flu.

In 2024 or so, Dr. Christakis said, the postpandemic stage will dawn. He said it will be “a little bit of a party.”

“When the war is over, when the famine is done, when the earthquake stops, when the pandemic ends, people rejoice. The survivors rejoice,” he said.

Until then, he said, the country faces a reckoning: “During the next phase, it’s like the waters of the tsunami have receded, and now we’ve got to clean up.”

The $6 trillion or so added to the national debt will have to be paid off. That likely means higher inflation, which will hit Americans’ wallets.

The nation already is seeing some of that, with inflation hitting 40-year highs, as well as other economic aftershocks.

The Great Resignation has forced companies to rethink wages, benefits and working conditions to keep or lure back employees.

That hasn’t been enough for millions of workers. The workforce participation rate, which ticked up in the Trump years, fell 3 percentage points in the first several months of the pandemic, affecting millions of people. It has rebounded somewhat but is still 1.5 points lower than prepandemic levels.

Some older workers retired earlier than expected. Others are parents, usually women, who ditched jobs to deal with children out of school or to take care of ailing parents.

“A lot of people left the labor market, and they’re not going to come back,” Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan said at an event hosted by the World Economic Forum and Fortune.

Analysts are tracking not only the rise in mortality but also a significant birth dearth as women’s fertility rates plummet to record lows.

The long-term prospects are not clear. Some projections show a lasting deficit sapping the economy of workers. Others, including the folks at the Social Security Administration, say it’s just a blip and women will make up for the lost babies in the next few years.

Then there’s the massive loss of trust in institutions — and in one another. Masking and vaccine status have become political dividing lines.

“I’m ashamed of us as a nation right now. We have not come together as a people to confront this external threat,” Dr. Christakis said. “I think people should communicate their political identity by using bumper stickers or lawn signs, not by whether they wear a mask or get a vaccine.”

Social headwinds

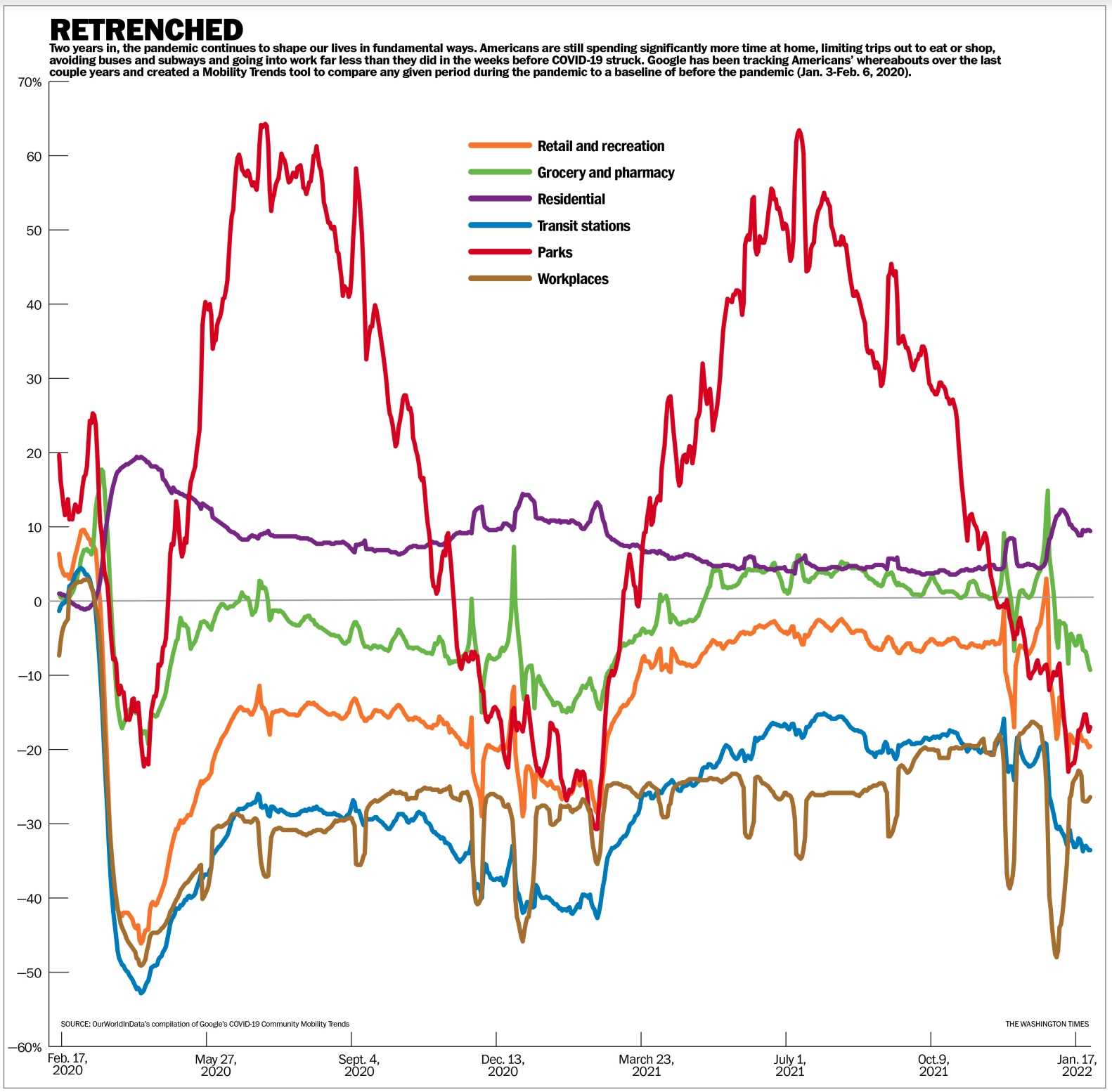

Measuring softer changes, such as interpersonal interactions, is tougher. Some indicators, such as Google’s “mobility trends,” track where Americans have been spending their time during the pandemic.

At the height of lockdowns in spring 2020, people were spending 50% less time at their workplaces. Some are returning to the office two years in, but Americans are spending about 20% less time at work — even in red states, where pandemic defiance is high.

Transit use has taken a nosedive, and visits to retail and recreation spots are still below normal.

Meanwhile, time spent at home is up, according to Google’s numbers.

The Census Bureau, which has been keeping tabs on Americans during the pandemic, said the number of people who “sometimes” or “often” don’t have enough to eat has nearly doubled.

About a third of the country is experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder. That is nearly three times the prepandemic rate of about 11%, though it has improved since late 2020, when more than 40% reported symptoms.

Parenting message boards crackle with debate over whether masking in day care centers and schools has sapped primary school students of nonverbal cues for learning and left toddlers slower to speak.

Research suggests that some babies born during the pandemic also struggle with motor skills. The reasons aren’t clear.

Other studies indicate that childhood obesity has increased.

The headwinds add up.

“Kids are missing out on a lot of important developmental tasks they should be going through,” Mr. Furr said. “They’re just not having as many opportunities. These are things like problem-solving, learning to deal with other people, learning to deal with organizations like schools.”

The debates about school are microcosms of the larger fights rending the country over masking, vaccine mandates and whether the social costs of distancing are greater than the disease.

What is and what may never be

The pandemic gave the world a sense of how intrusive people have become.

Global greenhouse gas emissions dropped as humanity shut down activities, though people were pumping out carbon and methane at nearly the same rate as before the pandemic by the end of 2020.

Despite the carbon holiday, which scientists dubbed the “anthropause,” researchers at the California Institute of Technology found that concentration levels in the atmosphere rose as if emissions hadn’t dropped.

Lockdowns emptied city streets of people, and wildlife crept in.

Fewer cars meant less roadkill. Nitrogen dioxide, a key air pollutant from sources such as power plants and vehicles, also dropped.

Curiously, fewer people on the roads meant more chaos, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration said. Traffic deaths rose 7% in 2020.

Even though people logged fewer miles behind the wheel, they were driving more recklessly, police say.

Emerging from the pandemic traffic lull didn’t seem to help. Americans increased their miles on the road in early 2021, and traffic deaths soared. NHTSA recorded the largest-ever increase in fatalities during the first half of 2021.

Some pandemic predictions await final judgment. President Trump, for example, wondered whether the handshake would disappear as the standard greeting in the West.

Debates over globalization and the costs and benefits of worldwide supply chains are still raging.

A recent post on Reddit, a major social media site, asked people to share something COVID-19 had taken away that won’t be coming back.

Among the mentions were lost parents, closures of favorite bars and restaurants, upheaval in the economy and the workplace, and losses of faith in institutions.

Asthma sufferers said a simple cough on the street, which used to elicit little reaction, now sends people scurrying like a gunshot.

Others reported diminishing lines between public and private time. If schooling can be accomplished virtually at home, then there is no reason for sick days or snow days. If work can be done at home, then there is no such thing as downtime or sick days. Any hour can be a work hour.

Some reported lost connections: less time with a new niece or an aging parent, or a tougher time connecting with friends. Indeed, lost time seemed to be a common thread.

Robbie Samuels sees a bright side to the reshaping of social interactions. The self-described extrovert, who works as a networking expert helping companies develop online events, said virtual space has given him more chances to have meaningful relationships.

“I have met more people and formed deeper relationships since March 2020 than I did the five years prior,” he said.

In fact, he said, he attended an in-person event late last year in New York and found it to be taxing in surprising ways. He ended up feeling “oversocialized.”

Figuring out how to reengage in person will be a challenge for many.

Mr. Samuels said he hopes folks don’t leap back into society without stopping to ponder the trade-offs. Scheduling interactions during the pandemic has made them more intentional, and he said that’s worth keeping.

“Two years from now, I’m going to be going to more in-person things, but I’m going to be more thoughtful about what I choose to leave the house for,” he said.

For more information, visit The Washington Times COVID-19 resource page.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.