OPINION:

A year ago, President Biden announced the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan had begun. Brimming with confidence, he assured the American people that the withdrawal would be orderly, that Americans and our allies would be evacuated safely, that the Afghan military was capable of preventing a Taliban takeover, and that Afghanistan would not again become a base for terrorists to attack the U.S.

All of this proved false. The withdrawal was a debacle. U.S. citizens and Afghan allies were stranded. The Taliban took over almost immediately, and Afghanistan is once again a haven for terrorists.

Unsurprisingly, under the tender mercies of the Taliban, Afghanistan has become a humanitarian and human rights disaster. Afghanistan has never been a rich country. But since the Taliban seized control, the economy has crashed. By year’s end, GDP is projected to be 34% below the 2020 level. Jobs have evaporated. Inflation has soared, putting basic household goods beyond the reach of many. Desperation has led families to sell their children or their organs to survive.

A recent earthquake and persistent drought have compounded man-made suffering.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reports, “Afghanistan, which has endured repeated humanitarian crises, faces its darkest time.” UNHCR estimates that 24 million Afghans — roughly two-thirds of the population — need humanitarian assistance.

Understandably, the U.N. and philanthropic organizations have called for sanctions relief and humanitarian aid. But with the Taliban in charge, providing relief is complicated.

When the Taliban first seized control of Afghanistan in the 1990s, the fundamentalist movement imposed a strict version of sharia featuring public executions, banning music and cinema, requiring women to wear the burka and opposing the education of girls beyond age 10. Taliban support and sanctuary for al Qaeda enabled the killing of nearly 3,000 people on 9/11.

To woo foreign support after the U.S. withdrawal, the Taliban promised to change its ways and respect human rights and equal treatment of women. This promise was quickly broken. The repression and abuse have resumed. Likewise, the Taliban predictably continued to support Islamist terrorist groups, despite promising otherwise. In fact, the U.S. recently killed the leader of al Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri, at a home in the heart of Kabul.

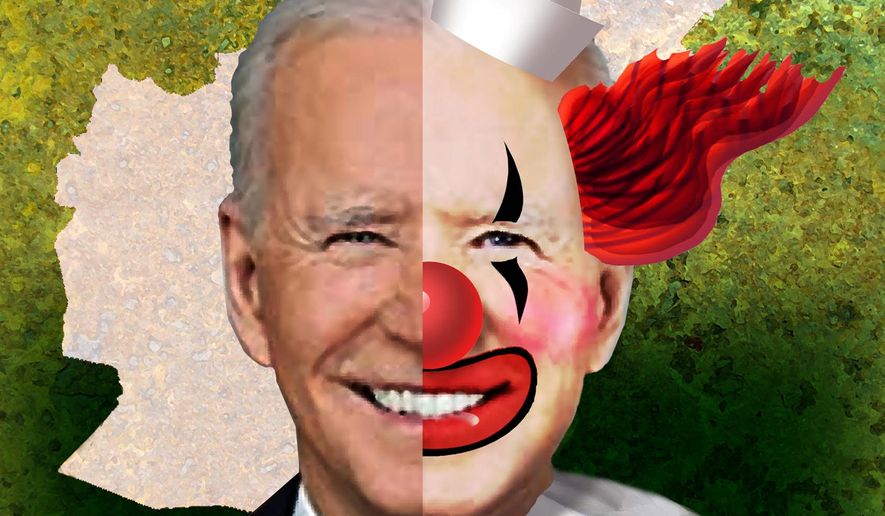

One year on, the Biden administration’s disastrous Afghanistan policy spawned a humanitarian and human rights disaster and empowered an extremist threat to the U.S. It has also created a dilemma. Attempts to alleviate the suffering of the Afghan people through aid or sanctions relief will, inevitably, result in a portion of that aid going to one of the world’s most odious governments.

The U.N. is eager to open the flood gates, urging the end of sanctions and an increase in aid. China and other nations have also criticized sanctions and called for engagement with the Taliban. Hoping to capitalize on the June earthquake, the Taliban called on “the world to give the Afghans their most basic right, which is their right to life and that is through lifting the sanctions and unfreezing our assets and also giving assistance.”

Even for international relations, this is depressingly cynical. The Taliban is essentially using the suffering of the Afghan people — suffering that it is in great part responsible for — to extort support from the international community.

Nonetheless, as is its wont, the Biden administration’s decisions increasingly lean toward appeasement. Despite knowing the risks of aiding the Taliban, the U.S. has provided nearly $800 million in humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan since last August. It has loosened restrictions on financial transactions and worked with NGOs and the U.N. to facilitate their efforts. It is also negotiating with the Taliban to allow funds frozen by U.S. sanctions to be used for humanitarian purposes.

While they may think they are helping the Afghan people, the reality is that as it provides more aid and loosens sanctions, the Biden administration is rewarding the Taliban for its grievous abuses of human rights.

Although the U.S. insists that it is “too early to look at [formal] recognition” of Taliban rule, the trajectory is clear. The slow erosion of punitive measures designed to hold the Taliban accountable will eventually culminate in acceptance. Already, the Taliban is audacious enough to run for a seat on the U.N. Human Rights Council and will again seek U.N. recognition to represent Afghanistan in the world body after failing last fall.

What a comeuppance for the “adults in the room” who promised to “bring to bear all the tools of our diplomacy to defend human rights and hold accountable perpetrators of abuse.”

• Brett D. Schaefer is the Jay Kingham senior research fellow at The Heritage Foundation’s Thatcher Center for Freedom.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.