OPINION:

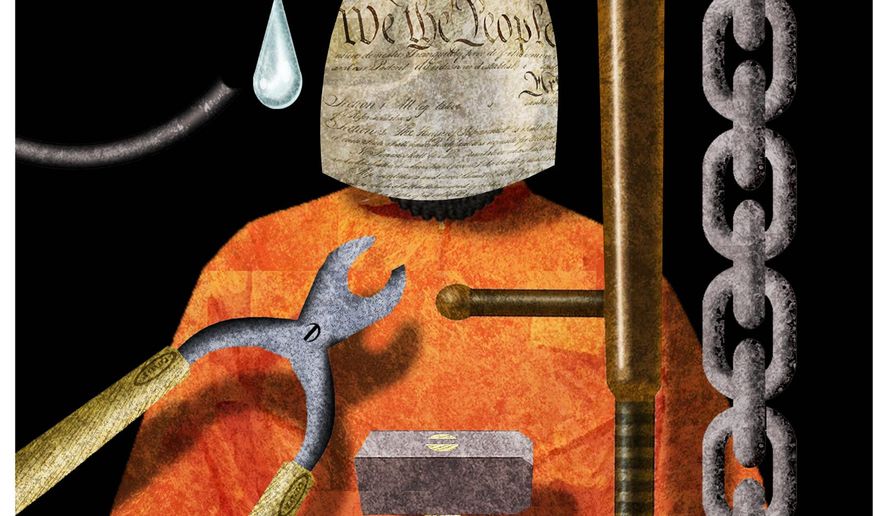

During the past three weeks, some unexpected government events occurred, exposing more government crimes and lies.

In the Supreme Court, the Department of Justice claimed that while the government knows about torture during the presidency of George W. Bush, nevertheless, because the U.S. is still at war, it can refuse to provide documentation of the torture to Polish prosecutors who are trying Polish intelligence agents for torture committed in Poland at the direction of the CIA.

The DOJ told the court the U.S. is still fighting against the Taliban in Afghanistan. The government not only tortures and kills, but it also lies laughably to federal judges.

Two weeks later, for the first time in the post-World War II era, a defendant testified in a public courtroom about two years of torture inflicted upon him by CIA agents.

The torture consisted of repeatedly forcing water up his nose, beatings to his head and ribs, chained naked confinement for days in a government refrigerator, weeks of sleep deprivation, force-feeding through his rectum, and rape. Yes, rape.

Majid Khan told the court, “The more I cooperated, the more I was tortured.” The courtroom setting was Mr. Kahn’s sentencing hearing at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for his guilty plea nine years ago to being a money courier to folks he didn’t know and who apparently years later used the money he brought them (isn’t money fungible?) to kill innocents in Indonesia, which happened during his CIA confinement.

Then, for the first time in the modern era, prosecutors acknowledged the defendant’s torture in a public courtroom. They told the military jury that Mr. Kahn is lucky to be alive — after what the CIA did to him, surely an understatement.

In civilian courtrooms, where the Constitution is taken more seriously, and where the judge and jurors don’t work for the prosecutor — the Secretary of Defense — as is the case in military courtrooms, a finding by the judge that the government tortured the defendant is sufficient to invalidate the entire prosecution.

As well, in Mr. Kahn’s military prosecution, where the jury — not the judge — does the sentencing, the government declined to challenge Mr. Kahn’s description of his torture, thereby validating it.

Why did the government, which, since 9/11, has repeatedly and forcefully denied that any of its agents engaged in torture, now in 2021, silently acknowledge it? Because it could only challenge it by putting Mr. Kahn’s torturers on the witness stand.

That would have exposed the Bush-Cheney regime to harsh front-page obloquy, particularly when defense counsel cross-examined the torturers — another first in the modern era, had it occurred — about who ordered the torture and whether the torturers received pre-prosecution pardons from Bush.

In another first, seven of the eight members of Mr. Kahn’s jury wrote to the judge. They condemned the government’s behavior characterizing it as “a stain on the moral fiber of America.” This was from senior military officers on the jury. It constitutes an unprecedented public rebuke of the CIA, which conducted the torture, and the DOD, which tried to cover it up.

While Mr. Kahn was giving his testimony at Gitmo, a federal judge in Washington ruled that the government had no basis to detain Assadullah Haroon Gul, who was captured in 2007 and has been held at the Gitmo prison since his capture. Mr. Gul was ordered released.

Why it took 14 years for his habeas corpus application to reach a federal judge is yet another testament to the government’s lack of fidelity to constitutional norms.

The DOJ under four presidents repeatedly persuaded federal judges to adjourn Mr. Gul’s habeas hearing while the CIA and the DOD searched in vain for evidence justifying his confinement.

That is not the way the Constitution works. Under habeas corpus jurisprudence, if the government cannot legally justify confinement at the initial stage — not 14 years later — the prisoner must be released.

There are some common threads in all these unexpected recent events, but little of this government criminality would have become known to the American public without a dogged press. Reporters from The New York Times and The Washington Post quite simply refused to accept the government’s whitewash of its criminal behavior and kept digging until they found the truth.

All of this represents a long train of the government’s callous indifference to the moral law, the Constitution and the federal statutes that everyone in government has sworn to uphold. This is not a Republican or Democratic failure; it constitutes criminality at the heart of government.

It is cutting constitutional corners to achieve a cheap courtroom victory.

It is civilian and military prosecutors and judges failing to take the Constitution seriously.

It is the perverse belief that because a defendant is not an American, he has no rights. This view is directly at odds with the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, which teach that our rights come from our humanity, not from the government.

It contradicts the constitutional provisions that protect all persons.

It defies the treaties to which the U.S. is a signatory.

It violates the federal statutes criminalizing torture.

We know today that when the Bush-Cheney regime first concocted the idea of a prison at Guantanamo Bay, Mr. Bush was told that because Gitmo is in Cuba, the Constitution doesn’t apply, the federal laws don’t apply and — best of all — those pesky federal judges can’t interfere with whatever he orders. The Supreme Court rejected all these arguments that first-year law students would know better than to offer.

Wherever the government goes, the Constitution goes with it. But without a moral sense of right and wrong, the government will do whatever it can politically get away with. Why does the government we have hired to protect our rights instead assault them? If it can torture and legally get away with it, is there anything it can’t do?

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is an analyst for the Fox News Channel. He has written seven books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.