OPINION:

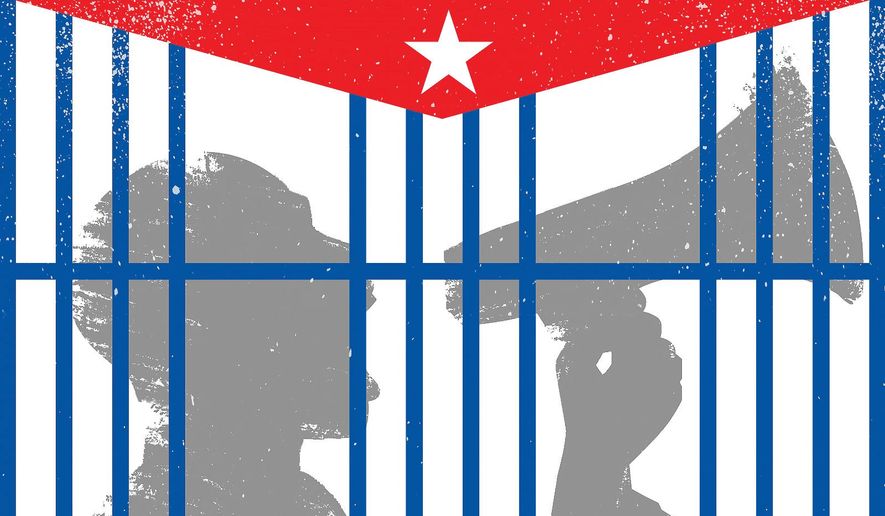

Havana, Cuba — On July 11, tens of thousands of Cubans poured into the streets in spontaneous protests against their country’s government. It was the largest demonstration on the island in generations, involving people from all walks of life.

Cuban human rights advocates and political dissidents planned to follow up with a nationwide march for freedom on Monday, Nov. 15, the same day that Cuba reopened to international tourism after suspending it during the pandemic.

This time, however, most Cubans stayed home in the face of government pressure, prompting many to wonder whether Cubans have lost their nerve to fight against the communist regime.

But the Cuban government has spent the last four months ruthlessly cracking down on protesters and instilling fear in all Cubans about the consequences of dissent. In the face of such suppression, it is no wonder the protests fell flat.

According to one estimate, more than 500 July 11 protestors are still being detained by the government. Dozens who were apprehended remain unaccounted for. More than a dozen protestors have been sentenced to prison terms in summary trials lacking due process.

But these are only estimates. There is no transparency. The regime has not said how many protestors are in custody, and it often ignores requests for information from family members of the disappeared.

The Cuban government’s secrecy is deliberate. It doesn’t want the public to know how many people are in its custody or what it has done to them. Many whose loved ones have been detained or disappeared are afraid to speak up. The Cuban government does this to instill fear in anyone else who may consider protesting in the future.

The charges against the protestors are often vague — “public disorder,” “defamation,” “illicit protests,” or “disobedience.” Dozens have been accused of breaking COVID-19 restrictions and charged with “propagation of an epidemic” for reasons that obviously have nothing to do with public health.

Cuba’s government officially banned Monday’s protests. State police flooded the streets of Cuba’s large cities at the time the protests were scheduled to occur. Prominent dissidents were arrested before the protests or confined to their homes to prevent them from participating.

This is how Cuba’s government works. Once it identifies you as a threat, it subjects you to arbitrary detentions, beatings, police harassment, surveillance, and searches without probable cause. Many Cuban activists have been forcibly exiled.

Those who speak out publicly risk losing their jobs or having their homes staked out by police. The state-run media might defame them as delinquents and looters, as they did to many peaceful July 11 protestors. If the family of a detainee speaks up, it may prompt an even harsher sentence.

This regime’s brutality is nothing new — it has acted this way since the beginning. In the immediate wake of the Cuban revolution in 1959, thousands of young people were killed for heroically resisting communism. Many shouted: “Long live free Cuba! Live Christ the King!” as they were lined up and shot.

Armando Valladares, the author of Against All Hope, described how as a young bank employee, he had refused to put a sign on his desk supporting the late Fidel Castro that said, “I’m with Fidel.” For this, Valladares was absurdly sentenced to 22 years in prison, many of which he served in solitary confinement.

Likewise, at least one July 11 prisoner is facing a 12-year prison sentence for tearing apart a poster of Mr. Castro. Some incarcerated protestors report being punished for refusing to shout, “long live Fidel!”

I met a woman who, after learning that her son had been jailed for participating in the protests, walked to the police station to demand his release. She was immediately interrogated and strip-searched, exposing a shirt with the pro-freedom slogan “no more hunger.” The police tore off her shirt, handcuffed and beat her, then forced her to walk almost naked in front of the other officers.

“They beat me mercilessly,” she told me. “So many blows that I wet myself.”

Several people have told me their loved ones have been given years or decades-long prison sentences for actions such as breaking a painting of Mr. Castro, or merely for participating in the protest.

To instill even more fear, the government recently enacted a law, Decree 35, that punishes free speech over the internet as “defamation against the country’s prestige.” Decree 35 makes anti-government speech a crime — anyone deemed to “subvert the constitutional order” will be considered a cyberterrorist. A special radio channel has also been created for citizens to inform on anyone who breaks the decree.

Not long after the revolution, the regime set up Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, a network of neighborhood groups across Cuba that it considers the “eyes and ears of the revolution.” The committees enlist ordinary citizens to spy on one another, looking for evidence of “counterrevolutionary activity.” Communist Party members harass and assault government critics in the streets, hurling insults, stones and eggs at them.

I have felt the wrath of the government for most of my adult life, starting more than 30 years ago when I exposed late-term abortion practices and infanticide in the Cuban health care system. I was suspended and later expelled from the Cuban National Health System, and my wife, Elsa, was also expelled from her job as a nurse.

Between 1998 and 1999, I was arrested or detained 26 times for speaking out against the suppression of civil liberties in Cuba.

In 1999, I was sentenced to three years in prison for insulting “the symbols of the homeland,” “public disorder,” and “incitement to commit a crime” because I had hung a Cuban flag sideways on my balcony during a press conference. Just 36 days after my release, I was re-arrested and sentenced to another 25 years, of which I served nine. My story is not uncommon.

The current crackdown is particularly brutal because most of the recent protestors are not activists but ordinary Cubans who have had enough and summoned the courage to stand up and resist.

The government believes that by silencing enough voices, it will stifle that courage, instilling the fear and passivity that have long kept it in power.

• Dr. Oscar Elias Biscet is a human rights leader, former prisoner of conscience, and recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He lives in Havana, Cuba, and can be contacted through his website: OscarBiscet.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.