OPINION:

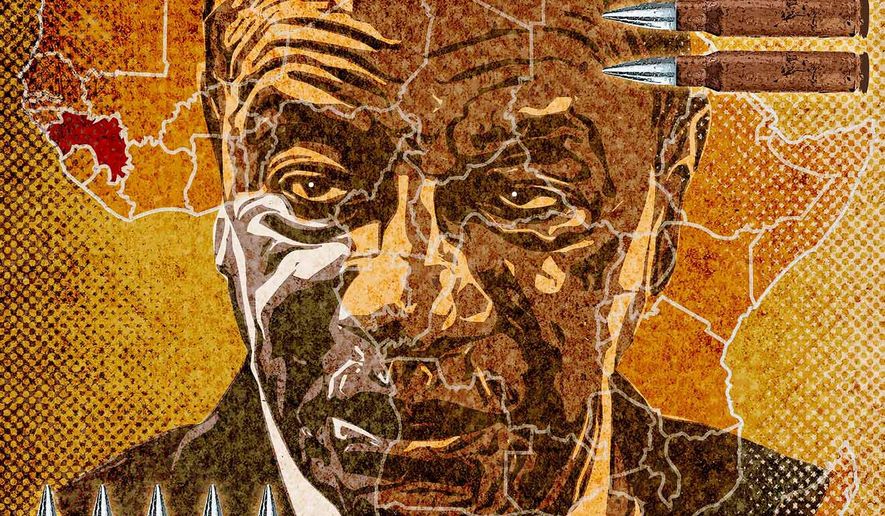

The September 5th coup in the tiny African nation of Guinea was roundly condemned internationally as a setback on Guinea’s road to democratic reform. Still, it was greeted in the country itself far differently. Hundreds of thousands of Guinea’s 13 million people took to the streets in wild celebrations as news spread that military units led by Special Forces Colonel Mamaday Doumbouya had ousted 83-year-old Alpha Conde, who had run the country since 2010.

These differing reactions to the coup raise the delicate and complicated question of whether and when a coup may be justified.

After years of struggle for independence from France followed by a series of authoritarian leaders and multiple coups, Guineans elected Mr. Conde President in 2010 in what most regard as Guinea’s first free and fair presidential election.

Mr. Conde had spent decades as the country’s leading human rights activist, had been sentenced to death, and fled to exile in France where he became an assistant professor of human rights at the Sorbonne, but returned and ran for president in 1993 and 1998. After the 1998 election, he was arrested and jailed and spent two years in prison, only to be released after the ruling junta agreed to elections in 2010 following the death of then-President Lansana Conte, who seized power in an earlier coup.

By then, Mr. Conde was described as “Guinea’s Mandella” and won an upset victory by voters who assumed his election would finally put Guinea on the road to democracy and stability.

That was not to be. The champion of human rights and democracy morphed into just the sort of autocrat he had spent a lifetime fighting. Mr. Conde won again in 2015, but already many earlier supporters realized he was not the man they had elected five years earlier. As the 2020 elections approached, Mr. Conde rammed through a constitutional rewrite allowing him to run again, curtailed freedom of the press, jailed his opponents and won another term in an internationally condemned sham election that effectively ended the democratic wave he had ridden to power ten years earlier. Mr. Conde, like others before him, tasted power, was seduced by it and decided that nothing in the world was more important than holding on to it.

The Economic Community of West African States or ECOWAS made up of many of Guinea’s neighbors barely objected as he transformed Guinea from an aspiring democracy into an authoritarian state but were outraged by his ouster.

As Foreign Policy magazine observed, “the regional and international condemnation contrasts with the celebrations of the coup in Guinea. Prominent civil society and opposition leaders … have welcomed the coup as a necessary evil to reverse the country’s descent into autocracy.” Guineans embraced the coup as a step toward restoring the democracy they had seen as their salvation.

After Nelson Mandela’s death, former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich responded to critics of the South African leader’s resort to force against the apartheid regime by asking, “What would you have done?”

Mr. Gingrich pointed out that the Americans who confronted the British at the Concord Bridge in April of 1775 realized they had no peaceful options. Declaring a year later that when a government denies its citizens certain “inalienable rights” the people have the right “to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

Revolutions and coups are messy and often make matters worse, so with the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, we institutionalized regular elections as a more peaceful way of ridding ourselves of incompetent, corrupt or obnoxious political leaders. Elections may not have been the perfect solution, but they were far preferable to having to hang a king every decade or so.

Mr. Gingrich was asking what a people were to do when faced with a tyrannical government that cannot be removed at the ballot box. Thomas Jefferson and the others who signed the declaration believed that a people having exhausted every peaceful alternative could seek justice through revolution or coup. That, after all, is what they did.

We were lucky. The American Founders could have taken the road that led to chaos in France and dozens of other nations since, but they didn’t. The initial signs are that Guinea’s military leaders may be taking our founders’ peaceful and just road. They have welcomed exiles back, encouraged opposition parties to reopen their offices, restored the rights of speech and press, and pledged an eighteen-month transition back to democracy.

Colonel Doumbouya has included opposition figures in his new transitional government, promised free elections in which he and those in his administration will not be able to run, and worked with domestic and international business leaders to avoid the chaos that often follows coups.

There will be bumps in the road, and the early promise could fade. Only time will tell, but if Colonel Doumbouya lives up to his word, he will have demonstrated that sometimes, under some circumstances, a coup can put a country back on the right track.

• David Keene is editor-at-large at the Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.