House Speaker Nancy Pelosi refuses to denounce her late father, former Baltimore Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., for supporting the erection of Confederate monuments in the city and perpetuating systemic racism by not stopping discriminatory practices, including refusing rental housing to Black people in White neighborhoods.

Mrs. Pelosi, who has made confronting the country’s past racism and combating systemic racism a cornerstone of the House Democrats’ agenda, refused repeated requests this week to address her father’s legacy.

Meanwhile, Democrats are pushing policies for White people to own up to their ancestors’ complicity in racism, including paying reparations to Black Americans.

“It’s hypocritical because she asks that of other people,” said Mike Gonzalez, a senior fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation. “Although, I have some admiration that she chose not to throw her father under the bus in the interests of being ‘woke.’”

D’Alesandro, who served as Baltimore’s mayor from 1947 to 1959, headed a city that was rife with segregated housing and schools. He occupied the mayor’s office when the Supreme Court issued its landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The court ruled unconstitutional the idea of “separate but equal” facilities that allowed the segregation of schools.

Baltimore moved quickly to desegregate its schools, and Mrs. Pelosi has pointed to it as a source of pride.

In her commencement address to the University of Baltimore School of Law in 2013, Mrs. Pelosi recalled watching her father be interviewed on television the day of the decision. “He said, ‘This is the law of the land, and it will be enforced and honored in Baltimore, Maryland.’” Mrs. Pelosi recalled. “And that was really important because it was such a landmark and it meant so much to Baltimore.”

Still, D’Alesandro had not championed desegregation, said Matthew A. Crenson, a Johns Hopkins University political science professor and historian of Baltimore politics.

Viewing D’Alesandro’s legacy on race poses the same issue as assessing the actions of any historic figure through the prism of modern norms.

In Maryland, the northernmost Southern state, it was significant that Mrs. Pelosi’s father did not oppose desegregation, said Kurt Schmoke, president of the University of Baltimore, who served as the city’s mayor from 1987 to 1999. Baltimore’s public school board is appointed by the mayor, and D’Alesandro could have resisted the court’s decision as did some governors in the South.

Mr. Schmoke recalled that D’Alesandro worked with Black political groups, which was significant at the time. He should be judged in the context of that time, he said.

Historians hardly consider Mr. D’Alesandro to have been a racist by the standards of his era. By today’s standards, however, D’Alesandro wouldn’t be considered woke.

D’Alesandro broke with other Maryland Democrats in supporting President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Decades later, his daughter is supporting another escalation in the government’s role of tackling societal problems in President Biden’s $4 trillion infrastructure initiative.

Mrs. Pelosi pushed the redress of grievances for slavery to the political forefront last year by demanding the removal of statues of Confederate leaders from the U.S. Capitol.

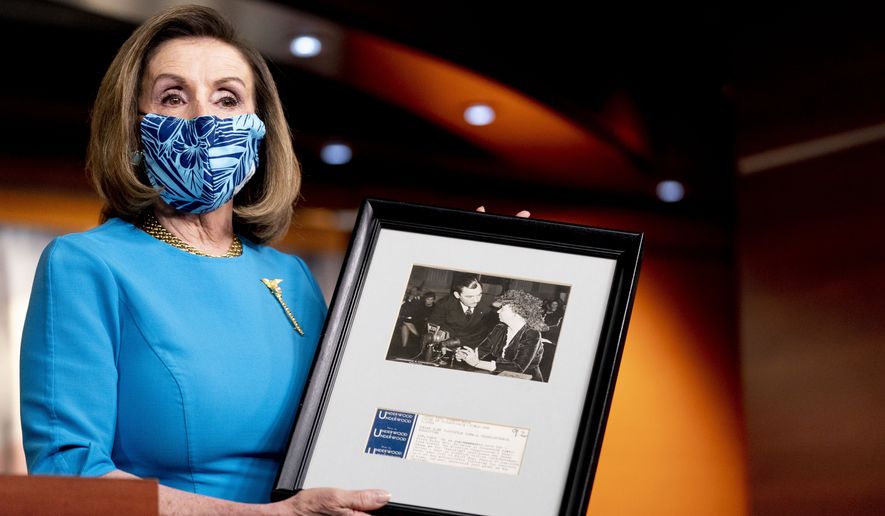

In 1948, her father took the opposite view. According to news reports from the time, he spoke at a dedication ceremony for a new monument in Baltimore honoring Confederate Gens. Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

He praised the Confederate icons and said the nation should look to them as examples.

“Today, with our nation beset by subversive groups and propaganda which seeks to destroy our national unity, we can look for inspiration to the lives of Lee and Jackson to remind us to be resolute and determined in preserving our sacred institutions,” D’Alesandro said at the dedication. “We must remain steadfast in our determination to preserve freedom, not only for ourselves, but for the other liberty-loving nations who are striving to preserve their national unity as free nations.”

He added: “In these days of uncertainty and turmoil, Americans must emulate Jackson’s example and stand like a stone wall against aggression in any form that would seek to destroy the liberty of the world.”

Mrs. Pelosi has said it’s wrong to put up monuments honoring Confederates. She wrote a letter asking Congress to remove 11 statues of Confederate leaders in the U.S. Capitol and said the monuments honor “men who advocated cruelty and barbarism.” The statues, she wrote, “pay homage to hate, not heritage. They must be removed.”

Mrs. Pelosi, though, refused to say last year whether her father was wrong to support the erection of Confederate statues in a city where many residents are descendants of slaves. She still will not address the issue.

Racist policies persisted when her father was in office. Redlining prevented Black people from getting mortgage loans to buy homes in White neighborhoods. The banks, not the city, enforced the practice.

But D’Alesandro’s City Hall did have a say about racist practices, including allowing landlords to refuse to rent to Black people.

D’Alesandro left race-based housing policies to his son, Mrs. Pelosi’s brother, Thomas D’Alesandro III, who served as Baltimore’s mayor from 1967 to 1971. He presided over the city during the race riots after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Mrs. Pelosi’s father wielded power at a time when political leaders in Baltimore were hoping to keep racial controversies from flaring. He was a Democratic member of the House of Representatives in the 1940s when White residents were fearful of a federal plan to build housing for Black defense workers during World War II in White parts of Baltimore. D’Alesandro cut a deal to have the housing built in industrial areas of Baltimore.

His son was “quite an open integrationist,” Mr. Crenson said. “One time when he was campaigning for mayor in 1967, he walked into a meeting where people were discussing preserving the city for White people. He went up to the dais and said, ‘I hope you will recognize that everyone has equal rights.’”

Mr. Schmoke said Mrs. Pelosi’s brother, who was criticized for not taking stronger police measures during the riot, hoped his support for civil rights and steps such as increasing the number of Black police officers would help answer Black residents’ calls for change and prevent violence. When it wasn’t enough, it devastated Mrs. Pelosi’s brother. “It took a toll on him emotionally,” Mr. Schmoke said.

Decades later, Mrs. Pelosi is pushing the idea that White Americans should make amends for the actions of their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers. While acknowledging the issue is challenging, she supported a Democratic bill passed last month by the House Judiciary Committee to create a commission to explore reparations for slavery to Black people.

Opponents say Whites would be paying for actions they had nothing to do with. Proponents say an acknowledgment of the past is needed.

Democrats also included in the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan some $5 billion in aid to non-White farmers. Opponents say the funding discriminates against White farmers based on their race, but Democrats say it is needed to make amends for the discrimination that Blacks and other people of color faced in receiving farm loans.

As Democrats look to the past, critics ask whether Mrs. Pelosi should address whether her father erred or did not do enough to advance civil rights.

“Instead of looking forward and solving problems, there’s this obsession of turning over every stone, in finding ways to blame Whites today for the actions of the past,” Mr. Gonzalez said. “She’s getting a taste of what she does to other people.”

• Kery Murakami can be reached at kmurakami@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.