OPINION:

“The worst class ever”: that’s how Nathan Pusey, Harvard’s then-president, described my undergraduate cohort of 1971.

With a half century’s leisure to contemplate that bitter judgment, I’ve concluded that he was just about right. Of course, one can’t be sure, as no one can know all of Harvard’s 385 graduating classes. I can assert, however, that ours was not just feckless in college — what Mr. Pusey observed and condemned — but in the 50 years since, when it actively joined in the degradation of American higher education and culture.

Though a blink in time, our collegiate years of 1967-71 witnessed the most far-reaching changes since the founding of Western higher education at the Universita di Bologna in 1088.

We entered a liberal university in 1967 and left a radicalized one four years later. Consider the innovations: pass-fail courses, student representatives on tenure committees, politicized “studies” departments and majors, relevancy the new yardstick. In addition, student life was transformed through co-ed housing, co-ed nude swimming, and an end to the dress code, ROTC and parietals. (As an experiment, ask someone under 70 what parietals means.)

These steps transformed the university from an institution encouraging free inquiry into one seeking to inculcate a message. Of innumerable examples (such as just 1 percent of the faculty identifying as conservative), take the fall of Larry Summers.

Many factors led to his abrupt departure as Harvard’s president, but central was his audacity to speculate, however cautiously, in a January 2005 talk on “Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce,” that “issues of intrinsic aptitude” may help explain the relative dearth of women in top positions in the sciences. This mild conjecture prompted a faculty revolt that forced Mr. Summers’ resignation. So much for free inquiry and the search for truth, or Veritas in Latin.

Speaking of Veritas, that is the bitterly ironic title of a book about Karen L. King, Hollis Professor of Divinity (the oldest endowed chair in the United States) at Harvard. It establishes how, blinded by her ideological fervor, the renowned professor fell for an blatant forgery, bringing shame on herself and disgrace on Harvard.

Lingering further on the topic of Veritas: Christi Gloriam (“For the glory of Christ”) served as Harvard’s motto during its first two centuries. To adopt to different times, that was changed to the secular Veritas in 1836. This motto now again being woefully outdated, it urgently needs to be replaced. Our class of ’71 should propose Propaganda. This Latin term has several advantages: it conveniently dates to 1622, or just before Harvard’s founding in 1636; it requires no translation into English; and it precisely captures Harvard’s new spirit which our class bumptiously promotes.

We were among the last to receive a solid, demanding, apolitical education; for this, I am deeply grateful. I learned from masters of their craft. Guided by them, I wrote classical music, puzzled over differential geometry, memorized Chinese dynasties, understood the importance of Marsilius of Padua, stumbled over Arabic grammar, and appreciated the impact of the Six-Day War. I relish that training the more knowing that few of today’s undergraduates experience anything like it (and, being the parent of a college junior, I know this first hand).

The politicization that our class promoted had the small consolation of teaching me some hard lessons. I broached pretend “picket lines” to eat the meals and attend the lectures my family had paid for. I argued with Progressive Labor cadres about capitalism and imperialism. I brought complaints against members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) for shutting down a Counter Teach-In that supported the Vietnam War. I wrote letters to the editor denouncing radicals (published in the Boston Record American) and criticizing faculty squishiness (in The New York Times).

That personal education has stood me in good stead and prepared me for 2020’s renewed radical moment of political correctness, de-platforming, cancel culture, and microaggressions.

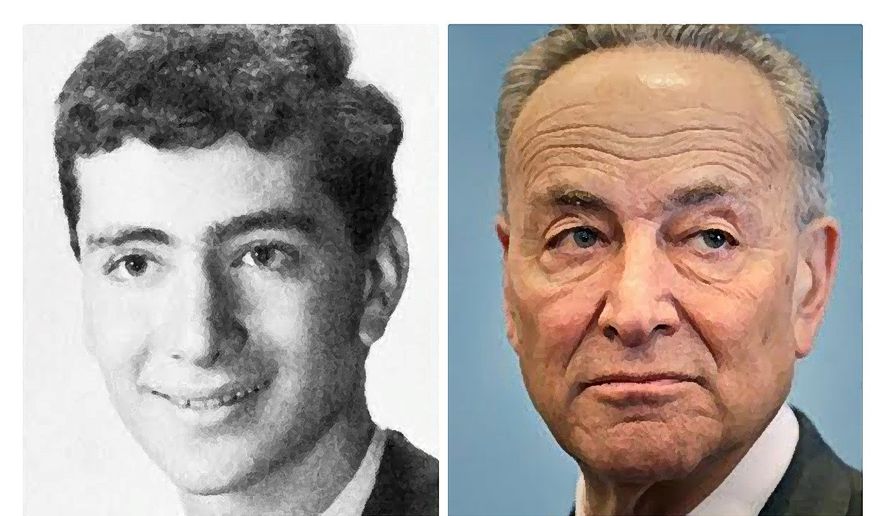

Our cohort did its share to transmute crazed ideas from the aeries of our ivory tower a half-century ago into the lunacy that has become dogma among half the American population. Our classmate Chuck Schumer symbolizes this extension. During Harvard’s years of revolution, he was president of the Young Democrats. Today, he is majority leader of the U.S. Senate. In both capacities, he triangulated between moderates and radicals; in both cases, he ended up facilitating extremism. His apprenticeship at Harvard prepared him well for national demolition today.

That is our dismal legacy.

• Daniel Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is the founder of Campus Watch.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.