Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who was billed as a jurist in the mold of the late conservative icon Justice Antonin Scalia, is raising eyebrows with early rulings in which she sides with the high court’s moderates.

Justice Barrett appeared to break with her mentor Scalia, for whom she clerked, when she joined the moderates and liberals on the bench in rejecting a pro-Trump challenge to Pennsylvania’s election laws and leaving in place some COVID-19 restrictions on houses of worship.

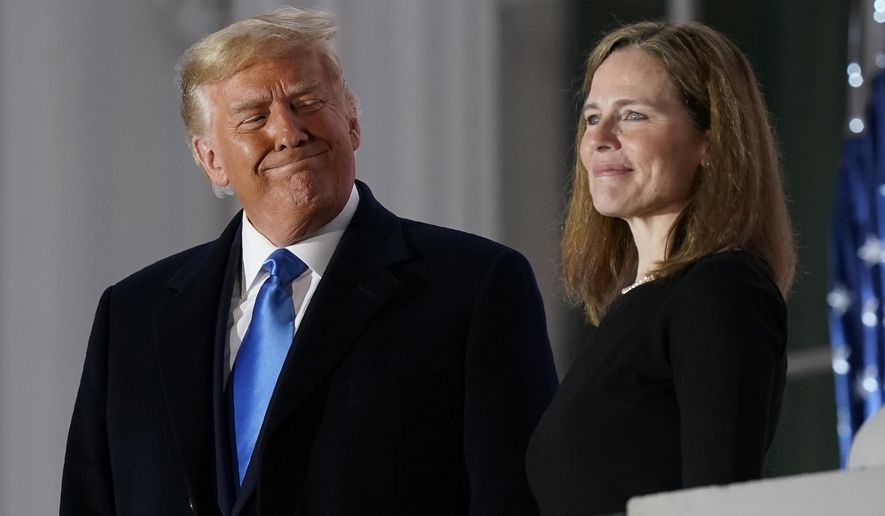

She was President Trump’s third high court appointee and has been on the bench for only about four months, not leaving much time for her to craft her own opinions.

She cast votes in a few pivotal cases, though, and aligned herself more with the moderate Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh than with more conservative colleagues such as Justices Neil M. Gorsuch, Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Clarence Thomas.

“I’ve heard some conservatives express frustration — sort of lump her with Roberts and Kavanaugh,” said Curt Levey, president of the conservative Committee for Justice.

During Justice Barrett’s confirmation hearings last year, Democrats pushed her to recuse herself from election-related cases and suggested that Mr. Trump nominated her to help his prospects.

She declined to say whether she would recuse herself. Just one day after she was sworn in, however, Justice Barrett did not participate in a challenge out of Pennsylvania in which state Republican lawmakers requested that the court expedite their case.

The challenge was brought in September. The Republican-majority Pennsylvania General Assembly said the state’s executive branch altered election laws by changing the deadline for mail-in ballots and allowing ballots with illegible dates to be counted.

The justices were not involved in the dispute until three days after the election, when Justice Alito ordered Pennsylvania to separate all late-arriving ballots while the case was pending before the high court.

On Feb. 22, the justices declined to review the case, which would have provided a vehicle for setting a standard on when and how state election laws can be altered.

Justices Alito, Thomas and Gorsuch dissented. It would have taken four votes to grant a review. Justices Barrett, Kavanaugh and Roberts declined to join them.

The court also rejected reviews of election challenges out of Wisconsin, Arizona, Michigan and Georgia.

“A lot of conservatives wanted the Supreme Court to take one or more of those election fraud cases, and she appears to be of no help there,” Mr. Levey said.

The decision not to hear the much-watched Pennsylvania challenge didn’t garner Justice Barrett any points with the left, though.

“The Trump election cases were so frivolous and presenting such ludicrous legal theories that it made it easy for even the most conservative and hyperpartisan judge to dismiss those,” said Dan Goldberg, legal director at the liberal Alliance for Justice. “I don’t read anything into the fact that she wasn’t willing to hear really frivolous legal claims.”

In another case from early February, the high court struck down California’s ban on indoor worship services. Under the 6-3 ruling, California must allow houses of worship to open at 25% capacity.

The three Democratic-appointed justices would have kept the ban against indoor church gatherings intact, but the majority agreed to allow indoor services with some limitations. They left a ban in place against singing and chanting, which displeased some conservatives.

Justices Gorsuch, Thomas and Alito would have granted the churches’ request to completely lift the restrictions.

Justices Roberts, Kavanaugh and Barrett kept a prohibition on singing and chanting until the churches could show evidence that it could be done safely or the state permitted secular businesses to allow similar singing and chanting.

“My best guess with limited data points is that she will be somewhere to the right of Kavanaugh and to the left of Gorsuch, Thomas and Alito,” said Adam Feldman, founder of the Empirical SCOTUS blog. “There is not much to go by yet in her Supreme Court decision making.”

Justice Barrett last week wrote her first opinion in a ruling that blocked environmental activists from obtaining internal documents from the Environmental Protection Agency.

In a 7-2 ruling, the high court sided with the EPA and against the Sierra Club’s Freedom of Information Act request.

In the 11-page opinion, Justice Barrett said that protecting preliminary discussions among officials allows them to communicate candidly.

“To encourage candor, which improves agency decision making, the privilege blunts the chilling effect that accompanies the prospect of disclosure,” she wrote.

Her opinion was joined by all of the Republican appointees and Justice Elena Kagan, an Obama appointee. Justice Kagan is the most moderate of the three liberal justices.

Elliot Mincberg, a senior fellow at the liberal think tank People for the American Way, said the opinion reveals a pattern of the newest justice in reshaping the high court.

“Her replacement of Justice Ginsburg has caused the Supreme Court to take another sharp right turn in a number of areas,” he said.

Mr. Mincberg, like conservative court watchers, said more will be known about Justice Barrett’s jurisprudence once she serves a full term. Her first year on the bench will conclude at the end of June.

“There are some far-right advocates that won’t be satisfied with anybody on the Supreme Court that doesn’t go with them every single time,” he said.

It isn’t unusual for conservative justices to stay away from controversial opinions during their first terms after going through contentious confirmation battles.

During Justice Barrett’s hearings, she faced personal attacks over her Catholic faith and decision to adopt children from Haiti. A liberal professor called her a “White colonizer.”

“For the conservative justices, when they go through a very difficult confirmation process … you kind of can’t blame them,” Mr. Levy said. “After you’ve been beat up and accused of things, it’s natural to lay low.”

• Alex Swoyer can be reached at aswoyer@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.