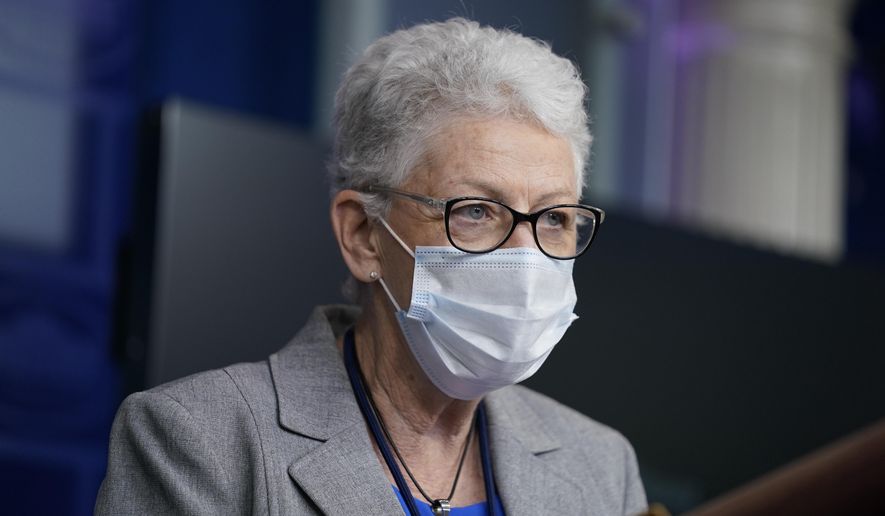

Gina McCarthy didn’t need Senate confirmation for her new role as the first White House National Climate Adviser but she emerged Wednesday as a stumbling block for President Biden’s other nominees for top environmental jobs.

Republican senators grilled two nominees — Janet McCabe for deputy administrator at the Environmental Protection Agency and Brenda Mallory for chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality — about their ties to Ms. McCarthy and her role in the Obama administration.

Ms. McCarthy served as an Obama-era head of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, West Virginia Republican, said the Biden administration was “shaping up to be a repeat” of the heavy regulatory regime under Mr. Obama.

“That agenda means putting Americans out of work through executive actions like canceling the Keystone XL pipeline, and rolling back commonsense regulations that protect our environment while keeping our economy moving,” she said at a dual confirmation hearing for Ms. McCabe and Ms. Mallory. “It means promising the world that America will double down on reducing emissions while countries like China and India get a free pass.”

Mrs. Capito warned of an “unelected and unaccountable bureaucrat” pushing policies that proved unpopular in the past, which she said included Ms. McCarthy.

Ms. McCarthy officially holds a strictly advisory position in the White House but critics say she will be the administration’s de facto leader on domestic environmental issues.

In this context, Mrs. Capito argued, it was important to understand the relationships that the president’s nominees had to Obama-era policy and Mrs. McCarthy in particular.

Both Mrs. McCabe and Ms. Mallory previously served as high-level political appointees under Mr. Obama. Each was central to his administration’s environmental policies and each worked closely with Mrs. McCarthy.

Mrs. McCabe served in the agencies’ office of air and radiation throughout the Obama years. In that role, she was not only Mrs. McCarthy’s principal deputy but also helped author the Clean Power Plan that required states to cut carbon emissions and which Republicans blasted as a job-killer.

Ms. Mallory was a senior-level EPA litigator for most of Mr. Obama’s first term and worked closely with Mrs. McCarthy. In 2014, Ms. Mallory ascended to the position of general counsel to the CEQ, a post which she held until the end of the Obama administration. In that role, she was instrumental in helping develop strategies to protect the administration’s environmental agenda from legal challenges.

Given the ties to Mrs. McCarthy and the new domestic climate czar’s wide-reaching but ambiguous advisory position, GOP senators repeatedly questioned who would have the final say on formulating environmental policy.

“How does this all fit together and who is lead here … who is going to be lead on environmental policies and whose voices should we be listening to,” Mrs. Capito asked.

Mr. Biden has made tackling climate change a top priority, including setting the ambitious goal of transitioning to 100% clean electricity by 2035.

Still, questions linger over who will be in charge of environmental policy under Mr. Biden.

Part of the confusion stems from the president’s promise of making climate change a “whole of government” approach. The White House has several top officials, including those of cabinet ranking, working on climate change. Those officials include Mrs. McCarthy, former Secretary of State John Kerry who serves as the president’s special envoy for climate, and Michael Regan, the president’s nominee to helm EPA.

At times, the climate officials have not been on the same page. This happened Tuesday when Mr. Kerry urged companies at the nation’s largest energy summit, CERAWeek, to move past oil and gas so as not to “wind up on the wrong side” of climate change.

His remarks were undermined on Wednesday by Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm in her speech at CERAWeek. She touted the “important element” that natural gas was playing in helping the country reach net zero emissions by 2050.

• Haris Alic can be reached at halic@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.