The Supreme Court on Tuesday delved into the Democratic Party’s lawsuit to ease Arizona’s restrictions on ballot harvesting and other election conduct, putting the high court at the center of a growing battle over how Americans vote.

The Democratic National Committee challenged Arizona’s election laws, which also limit ballots cast in the wrong precincts, as discriminating against minority voters in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

In oral arguments, Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich pleaded with the justices to set down rules because liberal groups have launched a nationwide legal campaign to upend state laws.

“The Legislature has to be able to enact common-sense voter integrity measures without worrying about an unelected group of judges striking it down because they didn’t like the policies,” he said. “The problem with that is it creates uncertainty. It creates chaos.”

Arizona’s legal battle gives the justices a chance to bolster a state’s right to determine how it runs its elections against a push from Democrats to relax voting requirements. The Democrats’ effort was largely successful ahead of the 2020 elections with lawsuits in several states to extend early voting and loosen rules for mail-in ballots.

Election law has become ground zero in the battle between the two major political parties, fueled by disputes over the 2020 presidential election.

Democrats want expanded mail-in voting and resist updating registration lists. They say more voting is more democratic.

Republicans want more measures to ensure election integrity, such as voter ID laws. They argue that lax security raises fraud concerns and undermines citizens’ faith in the democratic process.

If the standard on what violates part of the Voting Rights Act isn’t clearly set by the justices, the court could invite a host of lawsuits ahead of the 2022 and 2024 elections, said Ilya Shapiro, publisher of the Cato Institute’s Supreme Court Review.

“It’s more likely than not that the Arizona laws, which are fairly commonplace around the country, will survive. The real question is what kind of standard the justices set,” Mr. Shapiro said. “If the Supreme Court doesn’t draw clear lines, it will create a whole lot more work for itself.”

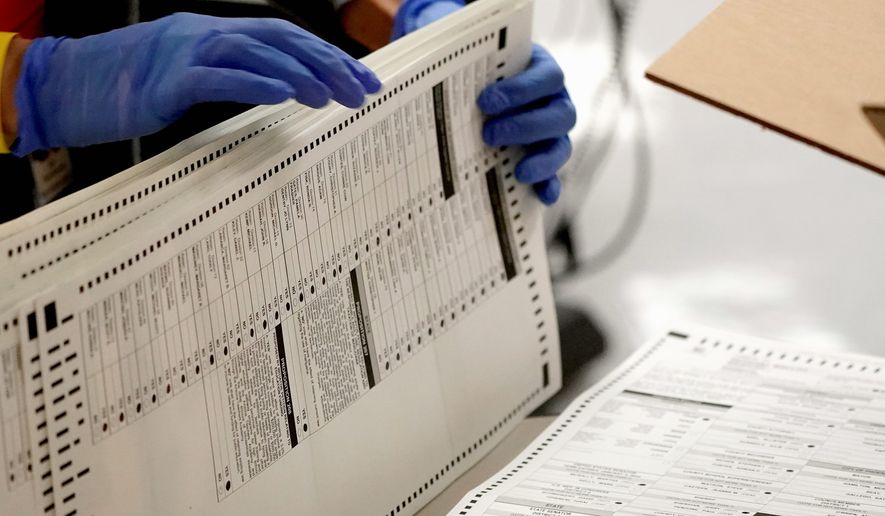

The Arizona case tests state laws that allow some counties to require voters to cast ballots only at designated precincts and forbid ballot harvesting, a practice in which someone other than a family member collects ballots from voters and submits them in bulk to election officials.

In Arizona, only a voter, family member, postal service worker or election official can return an individual’s ballot for tabulation.

The DNC sued in 2016 to change the law. A district court ruled for Arizona, finding that the state’s laws were not aimed at suppressing minority voters.

The committee argued that the laws disenfranchised Hispanic, Black and American Indian voters who had to wait in long lines at assigned precincts and may not have transportation to get to their polling locations.

The ruling against the DNC noted that about 99% of the minority voters cast ballots in the correct precinct.

The full 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the lower court. It ruled that the state enacted laws with discriminatory intent and that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is violated when “more than a de minimis number of minority voters … are disparately affected.”

“De minimis” refers to a number too trivial to merit consideration.

Mr. Brnovich took the case to the high court, which is expected to issue an opinion by the end of June. The ruling is expected to set precedent on limits of states’ election laws.

The justices appeared to break along ideological lines. The six conservative justices were open to Arizona’s argument that courts should consider how disparate an impact state laws might have in evaluating their legality and noted that less than 1% of minority voters were affected by the state requirements.

“In Arizona, we have numerous ways a person can vote,” Mr. Brnovich told the court.

The three Democratic appointees were more critical of the state’s case.

The DNC noted in briefs that the 9th Circuit found Arizona disenfranchised minorities twice as often as White voters and asked the justices to affirm the federal appeals court’s ruling against the state laws.

“What the 9th Circuit found was that really the state did not have a justifiable interest in continuing these policies,” said Bruce Spiva, a lawyer representing the DNC. “There is no longer any such justification for entirely disenfranchising people if they go to the wrong precinct.”

Dozens of lawsuits were filed over the 2020 election, which had a historic number of mail-in ballots because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before Election Day, liberal groups cited the pandemic in lawsuits seeking to strike down requirements for witness signatures, among other election laws.

After the election, several swing states counted a record number of mail-in votes for days, and Mr. Trump filed a slew of lawsuits claiming widespread voter fraud. He lost nearly all of the lawsuits as states began certifying their results in favor of Joseph R. Biden.

Mr. Brnovich said people thought there was nefarious conduct because election officials largely ignored concerns about voting integrity.

“Now we still have litigation ongoing as to testing the machines,” he said. “I think it is important for elected officials to take these concerns seriously.”

The case argued Tuesday represents one of the latest moves by liberal advocacy groups to strike down state election laws.

House Democrats also have been championing legislation for an election overhaul, known as H.R. 1, or the For the People Act, that would expand voting rights and impose limits on campaign financing.

It was the first bill introduced when Democrats assumed the House majority in 2019. House Democrats also reintroduced it as the first bill of the Congress in 2021.

The bill aims to impose some requirements that were struck down by the high court in 2013 from the Voting Rights Act of 1965, such as mandates that certain states and jurisdictions, mostly in the South, get pre-clearance from the federal government before changing any election policies to avoid discrimination against minority voters.

The Senate, under Republican control, never took up the bill. Now that Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer, New York Democrat, controls the chamber, it is likely H.R. 1 could get a vote. The problem for Democrats, though, is that it would take 60 senators in the upper chamber to pass the legislation and they hold only 50 seats.

Republican voters are fearful of the push from the left to nationalize election laws and strike down state restrictions. The Republican National Committee is backing Mr. Brnovich, saying the party wants to restore election integrity.

“Democrats are trying to manipulate a key part of the Voting Rights Act, distorting a safeguard against legitimate discrimination into a blank check that would allow progressive judges to strike down nearly any election integrity measure they disagree with and legislate from the bench. All voters must have confidence in the integrity and legitimacy of our elections,” said Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel.

• Alex Swoyer can be reached at aswoyer@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.