OPINION:

What holds a nation together? In some cases, it’s blood, soil and language (think Japan). In some cases, it’s a police state (think Iran).

But countries that are democratic and diverse, what we might call e pluribus unum countries, are apt to balkanize if their citizens don’t share values and interests.

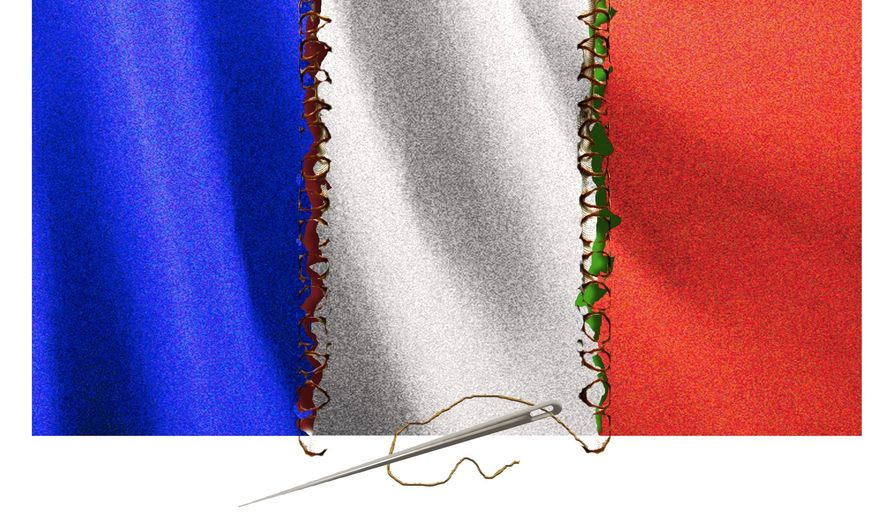

French President Emmanuel Macron has grasped that and, for the past few months, he’s been taking steps intended to reinforce a common identity, to unite the French nation.

“The fight against separatism” was the theme of a long and philosophical speech he gave in October, a week after the beheading of Samuel Paty. You may recall that Paty was a middle-school teacher who, in a class on free expression, touched upon the controversy over cartoons of Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. Sensitive to the possibility that such images might offend some Muslim students, he suggested they look away when he showed one.

The parent of a student who had not been in class that day heard about the lesson and complained on social media. Abdoulakh Anzorov, an 18-year-old Russian-born Chechen, decided it was his religious duty to punish Paty, and perhaps teach a lesson himself.

Mr. Macron called the brutal murder of Paty an expression of “radical Islamism,” which he defined as “another way of organizing society which is initially separatist, but whose ultimate goal is to take it over completely. And this is gradually resulting in the rejection of freedom of expression, freedom of conscience and the right to blaspheme, and in us becoming insidiously radicalized.”

Within Islam globally, Mr. Macron said, there is a “crisis” ignited by “radical impulses and the desire for a reinvented jihad, which means the destruction of the Other.”

He acknowledged that the response of the French government has been inadequate. “We’ve crowded people together according to their origins, their social backgrounds.” He called that “ghettoization.”

A complicating factor, he added, is that France is a “country with a colonial past and traumas it still hasn’t resolved.” This has resulted in “citizens of immigrant origin from the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa revisiting their identity through a post-colonial or anti-colonial discourse.”

“Children in the Republic who have never experienced colonization” have been led to see themselves as France’s victims rather than France’s citizens, he said.

The lethal consequences: “We previously faced imported terrorism. We now have what’s known as home-grown terrorism.” The most infamous example: French citizens with links to al Qaeda murdering more than a dozen people at the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical journal that published Muhammad caricatures.

Mr. Macron has announced a list of measures, including new legislation and stricter law enforcement, designed to “combat Islamism.”

A bill “reinforcing republican principles” passed one chamber of France’s National Assembly last month and is to go to the upper house at the end of this month.

Mr. Macron hopes to foster a “republican awakening,” “unabashed republican patriotism,” and the strengthening of laicity (laicite), a term that implies secularism as a policy and attribute — the idea that the French state is neutral regarding religion, and that French citizens refrain from prominently displaying their religious, ethnic, or other sub-national identities in public. “Laicity is the cement of a united France,” he said.

Because schools “are our republican crucible,” he vowed to limit “foreign influence.” An example: a school in Seine-Saint-Denis where the children are “greeted by women wearing the niqab. When you ask them, you find out that their education consists of prayers and certain classes.”

Such schools prevent children from “being educated about citizenship, from having access to culture, to our history, to our values, to the experience of diversity that lies at the heart of the republican school system.”

Perhaps most audaciously, Mr. Macron said that “this republican reawakening” could “build a form of Islam in our country that is compatible with Enlightenment values. An Islam that can peacefully coexist with the Republic.” He added: “We must help this religion to structure itself in our country so that it is a partner of the Republic on matters of shared concern.”

He added: “Every day people want to put forward good reasons for dividing us,” but the goal should be to “unite the nation.”

Some of President Macron’s critics say he is stigmatizing Muslims. Others accuse him of trying to steal a march on his right-wing rivals, in particular National Rally leader Marine Le Pen, who has been rising in the polls. I’d argue that when mainstream politicians ignore voters’ concerns, mouthing “politically correct” bromides instead, they only serve to empower extremists.

Will Mr. Macron accomplish his mission of melding France’s diverse and divergent communities? I think the odds are against him. But he deserves credit for trying.

America, too, is afflicted by separatism, an eroding sense of national community, belonging and purpose, coupled with hostility toward not just nationalism but also patriotism.

Disunification may be more advanced in the U.S. than in France. Not without reason has Mr. Macron urged that France reject “certain social science theories imported from the United States” — a reference to the “woke” ideologies that seek to splinter Americans into mutually antagonistic factions with weak national identities, and strong sub-identities based not just on religion, but also skin color, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, geography and ideology.

President Biden, like his French counterpart, has expressed a desire to bring his divided fellow countrymen together. “I don’t see red states or blue states,” he has said, “but only the United States.” If he’s serious about translating that vision into reality, more than the occasional rhetorical flourish will be required.

• Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and a columnist for The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.