This is the first in a three-part series.

Victoria Perez spent 10 months as a migrant smuggler. When agents finally caught up with her, she told them she had made $200,000 over that time, working two days a week, driving migrants through a Border Patrol highway checkpoint near El Paso, Texas.

She charged $1,500 per person when the checkpoint was operating but only $600 when the checkpoint was closed because the risk was low and the roads were wide open, she told agents.

The $200,000 she earned for what was essentially part-time work exceeds the annual salary of a member of Congress. It works out to three times the starting pay for a Border Patrol agent.

Perez was, in essence, a gig worker, contracting herself as a driver for a much larger organization.

It has become an accepted part of border wisdom that the surge of illegal immigrants is enriching the cartels. That’s true to some extent, but most of the money ends up not in the hands of the Gulf Cartel or Zetas, but in the pockets of people like Perez.

And 2021 is turning into a boom year. Based on the number of migrants and the prices they are paying, smugglers are easily on track for their biggest profits in history.

“Demand is so strong that the prices are going up,” said Todd Bensman, a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies who tracks smuggling tactics. “There’s huge, huge money being made right now.”

Talk to anyone familiar with the cartels, and they will inevitably start speaking in business terms. People are the product, and their families are the customers paying to smuggle them into the U.S. The cartels franchise the operations to coordinators and independent operators such as Perez.

What the cartels are selling is a vision: the American dream. People who have the cash or, more often, are willing to go into debt pay big money to chase that dream.

What the organizations bring to the table is logistics. The coordinators arrange housing, meals and transportation for tens of thousands of people each month who make the trip, and the cartels take a cut of the profit.

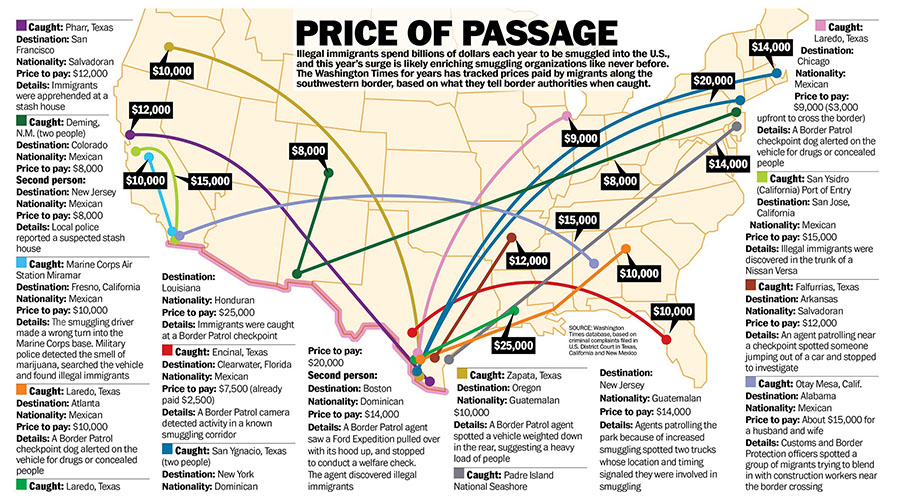

The Washington Times has tracked smuggling cases along the southwestern border for several years and maintains a database based on affidavits from Border Patrol agents, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, and Customs and Border Protection officers. The accounts in this article are chiefly based on those interviews.

According to The Times’ data, Mexicans paid an average of about $7,900 in February 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic upended cross-border traffic. The average payment this February rose to about $8,900. Central Americans’ average payment increased from about $9,400 last year to $11,000. Rates have held fairly steady in the months since.

Who’s getting paid?

For some migrants, the first contact with a smuggling organization begins in South America or even farther afield. Federal authorities in recent years have broken up several smuggling operations that they said specialized in guiding migrants from terrorism-tinged parts of the world such as Pakistan and Afghanistan. They travel through Brazil and then up the spine of the Western Hemisphere to reach the U.S. border.

Most of the migrants, though, are likely to begin their transactions with hawkers in plazas in southern Mexico or Central America.

Victor Manjarrez, a former chief patrol agent in the Border Patrol’s Tucson, Arizona, sector and now a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, said the scene is like something out of Las Vegas, where street hawkers pass out flyers for shows on the Strip.

The product the smugglers are selling is the fastest or safest trip north. In some cases, it’s a two-for-one promise: If you get caught the first time, then the smugglers will give you a second attempt free of charge.

Migrants fork out payments along the trip for every bus ride, boat trip or foot guide.

Darlyn Josue Mass-Montenegro, a Honduran man nabbed in 2019 as part of a group of 23 migrants in a truckload of watermelons, gave agents the breakdown of the $13,000 tab for reaching Los Angeles: $3,000 in Honduras; $1,500 in Monterrey and $2,000 in Tamaulipas, Mexico; $1,500 to the stash house operator who kept him holed up at a car wash in McAllen, Texas; and $2,000 in Houston. The remainder was due once he reached Los Angeles.

That doesn’t include out-of-pocket costs.

Many migrants who take the land route to Panama cross the forbidding jungle of the Darien Gap and emerge at the village of Bajo Chiquito. There, they pay $5 for a canoe ride downriver to a migrant camp. Such scenes are repeated dozens of times across a journey.

The big money, though, is collected near the U.S. border.

Someone usually houses the migrants on the Mexican side. Migrants owe a “piso” or “mafia fee” to whatever cartel controls the approach they’re taking to cross the border. They also must pay a foot guide to take them through the desert or someone to raft them across the Rio Grande, and a driver to pick them up and transport them to a stash house on the U.S. side, where they wait for a long-haul driver to try to get them through the network of Border Patrol checkpoints that act as secondary borders.

The checkpoint is the key step for most migrants. Once they make it through the checkpoint, they are in the interior of the U.S. and are unlikely to be caught, much less deported.

Drivers might earn about $50 per person to ferry migrants along local routes from the border to nearby stash houses.

Stash house operators get more. Eduardo Salinas, nabbed May 24 in Eagle Pass, Texas, by agents who heard he was threatening migrants at the stash house he was running, told agents he was paid $500 per person. He was holding six people at the time he was arrested.

Bringing food to a stash house can earn a couple of hundred bucks a week.

Scouts, who track Border Patrol movements or run interference on driving routes, also can make a couple of hundred per job.

Truck drivers are usually paid the most. A single run can net tens of thousands of dollars.

Richard Codoluto, nabbed by agents last month with 45 illegal immigrants inside his tractor-trailer, said he was getting $15,000 for the trip and had made 10 or so previous runs.

Rafael Cazarez, arrested May 28 near Laredo with a load of 54 migrants in a truck, told agents he charged a “flat rate” of $50,000 for each run. He said that was his eighth trip.

Some smugglers stop for food and pick up snacks for the migrants. Others treat them like merchandise. They lock the migrants inside compartments, zip them into suitcases or force them into car trunks.

Things can go tragically wrong, particularly in the summer heat along much of the border. Agents often take the temperatures of compartments where they find migrants stashed and regularly find the thermometer topping 100 degrees.

Agents at a California checkpoint nabbed two people carrying two illegal immigrants in the trunk of a Nissan Sentra in the June heat. Using a Fluke 917 Temperature Humidity Meter, agents measured 134 degrees in the trunk. The Mexican migrants had paid $8,000 apiece for the trip. The smugglers were sentenced to time served.

Two months later, agents at the same checkpoint in the desert just south of the Salton Sea found migrants stashed in the trunk of a Toyota Corolla. They recorded a temperature of 158 degrees.

Judges often respond with stiff sentences.

Juan Contreras was sentenced last month to nearly 11 years in prison for migrant smuggling — his third conviction — after he was found carrying 35 illegal immigrants in the trailer of his truck, which broke down on the side of Interstate 35.

The tow truck driver heard banging from inside the trailer and called Border Patrol. Agents arrived to find that the migrants had punched holes in the trailer to try to escape the heat. Two had passed out and were rushed to a hospital for treatment. Contreras admitted that he never tried to help the migrants.

The border surge this year has been accompanied by a rise in deaths. Drownings, death by exposure and highway accidents are increasing, law enforcement officials say.

Those who study the smuggling operations say rough treatment is common. They aren’t surprised when migrants are viewed as cargo or merchandise.

The FBI brought charges April 30 against two people who agents said ran an extortion operation in New Mexico, where migrants were held and beaten until their families paid extra. The violence was captured on video and sent to relatives to hasten the payments.

One family paid $7,000 to have a Honduran man released. Another man, from the country of Georgia, said his family paid $10,000.

That same day in Houston, police got a call from a woman who said she had paid $11,000 to smuggle her brother from Honduras into the U.S. and was told he was being held for an additional $6,300 ransom. Police tracked down the smugglers’ cellphone number, sent in a SWAT team and found 97 illegal immigrants stuffed into two rooms with deadbolt locks to prevent escape.

The need for cash during the pandemic has created a large pool of people willing to smuggle, but some stand out.

Perez, the woman who earned $200,000 in 10 months of smuggling migrants around a highway checkpoint, walked the route herself and mapped it out.

She knew the 2-mile hike took two hours. She would drop off migrants just west of the checkpoint, drive through the checkpoint alone and then wait a couple of hours at a rest stop before heading to the pickup spot. Her usual destination was Dallas.

Perez was nabbed in December 2019 while dropping off 12 people before the checkpoint. At $1,500 a head, she stood to make $18,000 for that load alone.

She told agents her employer was a man in a Juarez, Mexico, prison and paid her by MoneyGram.

Perez pleaded guilty to that smuggling charge and was ordered to report to prison six months later, but she was arrested again in another smuggling attempt in May 2020. She told agents she was trying to make some quick cash to support her son while she was behind bars.

Francisco Javier Ayala-Reyes, arrested at a Border Patrol checkpoint in Texas in October with two illegal immigrants in his SUV, told agents he had been involved in smuggling since age 11. He was to be paid $3,200 per person when he dropped off the two sisters in Houston.

He said he picked up the women from a stash house, where he saw 30 illegal immigrants as well as drugs. He selected the two women for the run because they looked the most “American.” He figured they would be less likely to be flagged at the checkpoint.

He told the women to rub some oil on their hands, but the oil turned out to have some properties of marijuana. When he arrived at the checkpoint near Sarita, a Border Patrol dog trained to sniff out drugs and smuggled humans alerted on the vehicle.

He was sentenced last month to time served in prison plus three months of house arrest. He also was ordered to undergo substance abuse treatment.

Ayala-Reyes preferred American-looking migrants, but Jose Rene Gonzalez told agents he usually asked for Chinese because they were usually smaller and easier to conceal. He got a 28-month sentence for a 2019 attempt.

Sometimes it is illegal immigrants who are pressured into doing the smuggling.

Agents this month nabbed a carload of migrants who said the smuggler insisted that one of them drive the SUV. The smuggler followed in another vehicle. Agents charged the Mexican illegal immigrant, who paid $10,000 for the trip and then got recruited to drive, but the man who orchestrated the scheme got away.

Who’s paying?

Taken as a whole, migrants are paying billions of dollars a year to be smuggled.

The rate can vary dramatically. It depends on where the migrant is from, the route they take and, in particular, how they choose to enter the U.S.

Among the more expensive options is being boated up the California coast and dropped off at a San Diego beach. Mexicans pay perhaps $15,000 for the trip.

Coming through an official border crossing stashed in a car trunk or stuffed into an aftermarket compartment between the engine and glove compartment — a surprisingly common method — also commands top dollar. A common rate in recent months is $18,000.

Chinese migrants smuggled through those border crossings pay the highest rates, according to The Times’ database, with some topping $70,000. The average rate is nearly $30,000.

Swimming the Rio Grande or walking over the border in Arizona or California is usually the cheapest way. Some migrants say they paid as little as $500, but a $20,000 tab is not uncommon for Brazilians and $17,000 is a frequent rate for Ecuadorians.

Mexicans usually have the lowest payments. Central Americans come in slightly higher.

Meralis Reanos-Canales told agents she paid $9,000 to smugglers for her journey from Honduras. She was shuttled between stash houses on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande before she got a chance to cross. She was given a wristband — a tactic smugglers use so they know who is going where — and then swam across the river as part of a group of 35 people.

Once on the banks in the U.S., the migrants ran away from agents before they were loaded into trucks and taken to stash houses.

Ms. Reanos-Canales said she went first to a trailer and then to a “factory,” where hundreds of people were kept. After two weeks and another $1,800, she was told she could leave. The smugglers put her into a Nissan Altima with a driver and three other migrant women. They made it through a Border Patrol checkpoint by lying about their citizenship, but a sheriff’s deputy later stopped the Nissan for speeding and uncovered the smuggling attempt.

Few have upfront cash for the trip. They borrow from family, friends or neighbors and sometimes go into debt to cartels with plans to work it off once they reach their destinations. Most find their own way to northern Mexico and hook up with smugglers for the final push into the U.S.

Mr. Manjarrez said 40 to 50 people can be involved in a single migrant’s journey, and each of them is getting a cut of the money.

Mr. Bensman compared it to a relay race, with migrants as batons handed off from one person to another.

Everyone knows their territory. Some specialize in mountains, and others get migrants onto the trains that run across Mexico. They have relationships with local authorities and know whom to pay to ease the passage.

Mr. Bensman once tried to arrange a fake smuggling trip north from Central America. He was told it would cost $1,000 just to move someone from Costa Rica to Nicaragua.

“They said, ’We need the money to pay the police,’” he said.

The cartels, which sometimes oversee the trips, come into play when it’s time to cross the border.

They control the approaches and charge for each crossing through their territory. Some agents refer to it as a “mafia fee,” and migrants call it a “piso.” The fee can range from a couple of hundred dollars to more than $1,000.

During a visit in the Rio Grande Valley several years ago, Mr. Manjarraz said, agents told him they had calculated that the cartel controlling the routes into that region made $100 million over the previous 12 months simply from fees paid by folks taking those routes.

That’s one cartel in one region of the border.

The Rand Corp. developed its own estimates. It calculated that pisos paid by migrants from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala in 2017 ranged from $30 million to $180 million.

’The winners are the cartels’

Like so much about illegal immigration, a massive range of uncertainty is involved. For one thing, it’s impossible to know exactly how many people are coming across the border.

The government reports arrests, but Customs and Border Protection declined to release its data to The Times on “gotaways,” or migrants known to have crossed but evaded capture.

In Texas, the Department of Public Safety runs a network of cameras at the border and calculates that the number of gotaways is up 156% from last year.

Cochise County in Arizona, which also runs its own camera system, calculated that only 27.6% of migrants spotted jumping the border from July through January were caught by Border Patrol agents.

Using that “probable capture rate” as a rough yardstick means that if agents borderwide nabbed 96,974 migrants last month, another 250,000 or so made it through. Even assuming the “gotaway” rate is higher in Arizona’s remote areas than in Texas, many people still don’t show up in the monthly apprehension statistics.

The gotaway numbers don’t account for those who sneak into the U.S. by hiding in car trunks, gas cans or other nooks and crannies in vehicles coming through the official border crossings or who are carried by boat or personal watercraft north along the coast.

Agents generally figure that the ratio of gotaways versus those apprehended is steady. If the rate of apprehensions doubles, so does the number of people who evade capture. That means the smuggling world’s income is growing along with it.

Given that Border Patrol arrests more than tripled from about 30,000 in February 2020 to about 97,000 last month, it stands to reason that the smuggling world’s income also has tripled, assuming all else is the same.

“The winners here in open borders are the cartels,” said Mark Morgan, a former chief of the Border Patrol and acting commissioner at Customs and Border Protection in the Trump administration.

Business is so good that operations are expanding. The Big Bend area of Texas, which is so rugged and remote that smugglers usually have avoided it, has suddenly become active.

“They’ve got so much revenue now and so many more resources available to them they’re able to take these tactics and open up new franchises now, and Big Bend is one of the franchises now,” Mr. Morgan said.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.