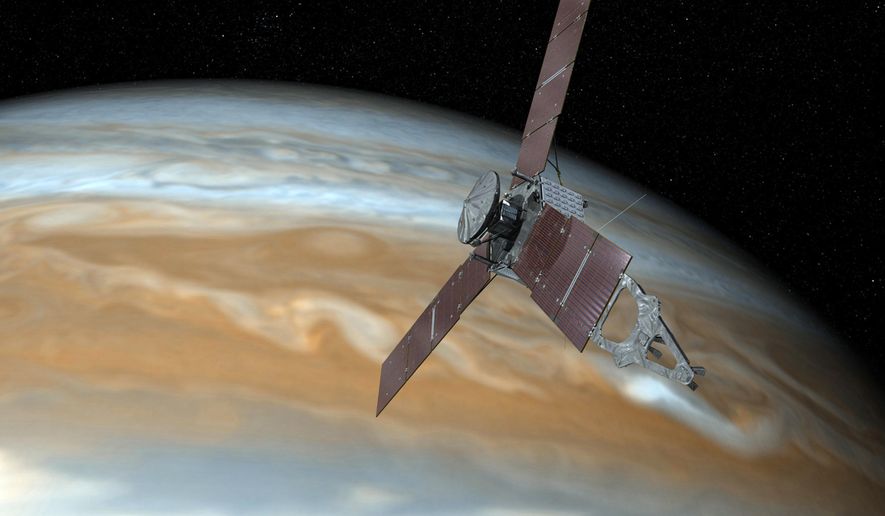

NASA’s Juno spacecraft zipped past Jupiter’s largest moon Ganymede Monday afternoon, the first close encounter with the celestial body in more than 20 years.

Juno was expected to come within 645 miles of Ganymede’s surface — the closest a probe has been to the solar system’s largest moon since Galileo flew by back in May 2000.

The flyby will allow scientists to not only snap photos of the moon, but also learn about the moon’s composition, ionosphere, magnetosphere and ice shell, NASA said Monday. The spacecraft will also measure the radiation environment near Ganymede.

“The whole team is really excited about this,” said Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “It’s the first time in a really long time and it’s the first time for us, for our spacecraft to get this close to a moon. So it’s really exciting.”

Ganymede is larger than the planet Mercury. It is also the only moon in the solar system with its own magnetosphere, which is a region of charged particles that encompasses the moon, according to NASA.

The flyby can provide scientists a snapshot of how the magnetosphere interacts with Jupiter’s magnetosphere and how well it protects the moon from the planet’s charged particles, said Mr. Bolton.

Juno was scheduled to start collecting data hours before its closest approach to the moon, including a peek into Ganymede’s water-ice crust to obtain information on composition and temperature.

“The composition of Ganymede is intriguing to us. One, it tells us something about how it was made, but we’re also interested in how it varies across the surface and how that is related to the features that we see when you look at an image,” Mr. Bolton said. “We know it is covered in ice. We don’t really know if there are compositional differences in that ice. There’s probably contamination, something other than water that might be mixing in.

“The ice may be hiding some liquid underneath and it’s certainly interesting just to understand how the ice shell of these icy bodies really works,” he said.

Juno will also send radio signals through Ganymede’s ionosphere, the outer layer of an atmosphere where gases are stimulated by solar radiation to form electrically-charged ions, as it passes behind the moon, causing small changes in the frequency that antennas at the Deep Space Network’s Canberra complex in Australia should detect, according to Dustin Buccino, a signal analysis engineer for the Juno mission at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California. This could help scientists understand the link between Ganymede’s ionosphere, magnetic field and Jupiter’s magnetosphere, he said.

A camera on the spacecraft should collect data on the radiation environment in the region near Ganymede by capturing a special set of images, NASA said. This will help characterize Ganymede’s radiation environment and therefore be useful for planning future missions.

The JunoCam imager should’ve also collected images during the Ganymede flyby at a resolution comparable to those captured from the Voyager in 1979 and Galileo in 2000. Scientists will analyze the images and compare them with those from earlier missions to see if there are changes to the surface features that might have taken place over the last few decades. For example, astronomers could gain a better understanding of the population of objects that affect moons in the outer solar system if there are any changes to the geology of Ganymede’s surface.

Although Ganymede is an icy moon far away from the sun, life on the celestial body is possible, Mr. Bolton said. The moon could have internal heat coming from its core or get heat from the “squeeze” of Jupiter’s gravitational field. Another theory is that there may be thermal vents down underneath an ocean, which some suggest could be the case with Jupiter’s moon Europa.

“If you did have an icy body that somehow shielded a liquid underneath, and that liquid had something, had some energy sources to it and nutrients and the right organic materials, you could get something like life there. Even if life isn’t there, it might be habitable, which maybe means life someday could form there even if it isn’t there now. That’s intriguing when we’re looking around the solar system and the universe and asking the questions, ’Are we alone? Is there life out there?’” Mr. Bolton said.

NASA said it anticipated Juno to zoom past Ganymede at almost 12 miles per second, allowing the spacecraft camera to capture about five images of the icy moon. Juno Mission Manager Matt Johnson of JPL said NASA also plans on conducting another flyby of Jupiter, traveling over the cloud tops at about 36 miles per second on Tuesday.

Juno will return for closer looks at Jupiter’s other large moons including Europa next year and Io after that.

• Shen Wu Tan can be reached at stan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.