The Cajun wings at the Penn Hotel Sports & Raw Bar had always been a big favorite on Yelp. Now, it seems, all anyone wants to talk about is politics.

Eric Nyman, the owner of the restaurant in Hershey, Pennsylvania, has been fending off jabs from political activists trying to drive away business after he led a lawsuit that helped block special COVID-19 relief privileges for minority-owned restaurants.

A Google reviewer said his lawsuit had taken away “the measley[sic] 13k we were approved for.” One Yelper took to talking about the size of his genitals. Over email, Mr. Nyman has been called a tool of “White supremacy.” One man has harassed him with repeated messages, one of which included the ominous promise that “I’ll figure out a way to get your attention.”

From Mr. Nyman’s perspective, he was fighting for his business and his employees when he went to court arguing that the racial preference program Congress and President Biden created for pandemic bailout money for restaurants was unconstitutional.

“That’s frustrating to see they were going to push somebody to the back of the line. If my application came in at 5,000th or 500th, that’s where it should have been processed,” he said.

A series of federal judges reached the same conclusion and blocked the program on grounds that it violated the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

Now political activists are furious at Mr. Nyman.

“This place sued the government to take COVID relief money away from struggling minority businesses. Give your business to restaurants not owned by resentful snowflakes,” Luke M., a resident of Virginia, wrote on Yelp.

A wave of one-star reviews poured in on Google. Like Luke M., the bad ratings came from folks who appear to live far from Hershey, and Mr. Nyman doubts they are actual customers.

Still, online brigading is a symptom of modern-day cancel culture politics, when trying to hurt a business is as easy as clicking a mouse button on a down arrow.

And unloading on Mr. Nyman is as easy as hitting “send” on an email.

“Affirmative action to aid groups and individuals who face structural discrimination is not itself discrimination. Undermining attempts at redress for historical discrimination upholds White supremacy,” one emailer wrote.

Another wrote: “Sure hope you’ll be able to struggle through with $640,000 of American taxpayer dollars as you sue to make sure that minority owners don’t get the same benefits of MY tax dollars.”

That understanding seems backward.

As the courts ruled, the set-asides were blocking access, and now all owners should have equal access to the same benefits, based on when they applied. Mr. Nyman does not have special access.

The Washington Times reached out to both emailers and received no response.

Brigading, or flooding a restaurant’s online reviews, over politics is not new. Conservatives did it when a restaurant refused to serve a senior Trump White House official.

In Mr. Nyman’s case, he is being punished for what the courts have ruled a constitutionally sound argument.

“It’s unfathomable that — in the year 2021 — we are actually having to fight the government about whether it can send one American to the back of a line based on the color of their skin, and send another American to the front of the line based on the color of their skin,” said Gene Hamilton of America First Legal, an outfit of senior Trump aides that now is involved in a number of lawsuits against the Biden administration, including Mr. Nyman’s case.

The $28.6 billion restaurant fund was part of the coronavirus relief package that Democrats pushed through Congress and Mr. Biden signed in March.

Knowing that the money likely would run out before all needy restaurants had a chance to apply, policymakers created a special three-week window at the beginning. During that period, only businesses owned by veterans, women or racial or ethnic minorities would be considered.

Lawmakers figured that a special carve-out would give them a head start after fielding complaints that minority businesses had struggled to access other pandemic relief.

The Small Business Administration was tasked with doling out the money. SBA said it received more than $72 billion worth of applications for the $28.6 billion allotted.

Some $27.4 billion has been paid out to more than 100,000 restaurants.

Mr. Nyman said businesses like his need the help just as much as any other restaurant, regardless of the race of the owner.

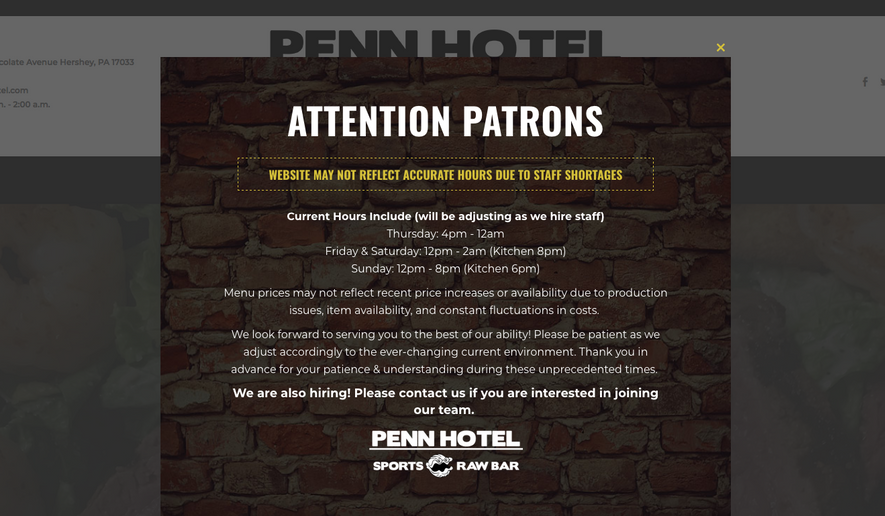

Normally, he would have a staff of at least 15 people. He has been operating with just six people and has had to curtail hours by canceling lunch service and closing around 9 p.m. rather than midnight. His usual capacity is 76 seats, but he has been operating at about 30.

“I’ve been working by myself in the kitchen,” he said. “I was never a cook. I am now.”

The government’s cash gives him more certainty about moving forward.

In many ways, it’s government itself that has left him struggling. Pennsylvania had among the strictest shutdown rules. All in-person dining was banned the week between Christmas and New Year’s, for example. As Mr. Nyman pointed out, nobody would be eating outside in Pennsylvania that time of year.

There is also the issue of workers.

Enhanced unemployment benefits have created a distorted labor market, with people who might otherwise have been seriously looking for jobs instead are collecting government checks that in many cases pay more than working would.

Mr. Nyman said he had scheduled more interviews over the past two months than he had in the previous seven years, but lining up new employees has been tough: “None of them show up for their first day, or even show up for the interview half the time,” he said.

Mr. Nyman was approved for more than $640,000 from the restaurant relief fund, though his legal team says that appears to have happened only after he sued. The money was disbursed only after a judge issued an injunction ordering the SBA not to penalize owners for being White.

Similar rulings were issued in two other cases.

The fact that Mr. Nyman got relief money has become a sore spot for critics.

The SBA, which had already completed processing of the special race and sex “priority” applications, said it went back and reprocessed all applications based on when they were received, without preference for race or sex.

That left 2,965 “priority” restaurants that had been told they would be getting cash, but under the new race-blind system applied too late and would not get the money.

That’s apparently what the Google reviewer complaining about losing “13K” was referring to.

The SBA, in court filings, blamed auto-generated notifications that were issued to the restaurants.

Congress created competition among businesses by allocating only $28.6 billion to the SBA’s fund. It could inject more cash — as much as needed to cover all proven needs — to eliminate competition among restaurants for limited funds and erase racial tensions.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.