OPINION:

Surprise! Surprise! Surprise! This past week, the Fed chairman and other Fed governors finally acknowledged what many of us have been writing and saying for months — and that is the rise in inflation may not be all that temporary or mild. The money supply last year grew at record rate — five or six times the normal annual increase. So, what did they think would happen with all of that additional money sloshing around?

Advocates of the New Monetary Theory argued that increases in the money supply no longer mattered, and if inflation did happen to rise, Congress could raise taxes to correct it. Others argued that due to the pandemic, people were not spending very much, and so the increase in the money supply was resulting in an increase in savings, which was not inflationary.

But now, as the economy reopens, people are spending their increased savings, including the government payments that most everyone received. The spending surge, coupled with the reopenings, has resulted in “temporary” surges both in the demand for labor as well as for goods and services.

To some extent, the temporary surge argument has some validity. Because of the pandemic, some inventories and capacity had been reduced, and it does take time to bring all of the global production back to full capacity. For instance, there is a shortage of shipping containers — but supply will soon catch up with demand. Other supply shortages will not catch up quickly.

Because of a variety of factors, the semiconductor shortage is likely to persist. The world’s most advanced semiconductors are largely produced by one company, TSMC, in one country, Taiwan — that is now years ahead of the global competition, both in technology and capacity. A state-of-the-art semiconductor manufacturing plant (called a “fab”) takes years to construct and test out and up to $20 billion to build.

By contrast, there is a temporary shortage of lumber (not of trees). Expanding or opening up new sawmills is something that can be done relatively quickly, and prices will probably fall back to near more traditional levels in a matter of months.

Other price increases are due to government-imposed restrictions on supply, such as all of the new restrictions on oil and gas production and development. Government-mandated increases in the minimum wage, more costly working conditions, and high unemployment payments for not working — all restrict labor supply, driving up the cost of goods and services.

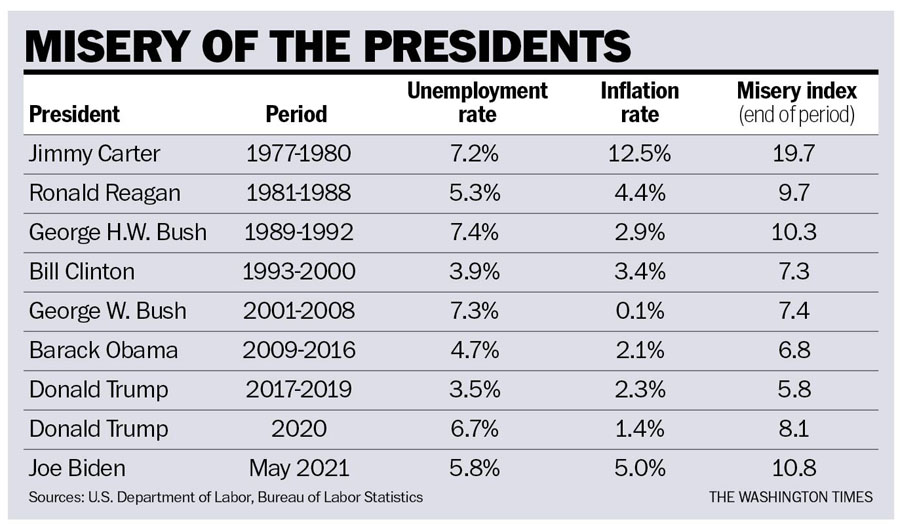

Those old enough to remember the inflation of the 1970s will recall it as not a pleasant experience. Art Okun (1928-1980), an influential economist at the time, developed the “misery index” which was the sum of the inflation rate and the unemployment rate. Everyone understands the misery that inflation and unemployment cause, whereas numbers like GDP growth rates are often harder to comprehend.

The accompanying table shows the misery index number at the end of each administration. At the end of the Carter administration, the misery index had reached a record high (19.7) which was instrumental in his defeat by Ronald Reagan. By the third year of the Trump administration (just before the pandemic), the misery index had fallen to the lowest level (5.8) in more than a half century, and that was the primary reason most observers thought that former President Trump would be reelected. But then came the pandemic — which caused the misery index to jump to 8.1, higher than when Obama left office (6.8).

Presidents are not held particularly responsible for the level of the misery index, but for the change in it during their time in office. When Ronald Reagan left office, the misery index was high (9.7) by recent standards, but less than half the rate that it had been when he took office from Jimmy Carter. Everyone noticed the improvement. Wages were higher and jobs plentiful, and inflation had been cut by two-thirds.

George H.W. Bush ignored the lessons of his predecessor and advice of many of his economic advisers and raised taxes and abandoned the spending goals he set when running for president. As expected, the misery index rose and he was not reelected.

The misery index fell under both of Bill Clinton’s terms, so Al Gore should have won, showing that an unlikable personality and a certain sleaziness can overcome the advantage of a lower misery index. When George W. Bush left office, the economy was in recession with a rising misery index — so the Democrat, Barack Obama, won. The misery index fell under Mr. Obama, but again the Democrats selected an even more unlikable candidate (Hillary Clinton), which was a throwaway for an election they should have won.

With reasonably sound economic policies, the Biden folks ought to be able to bring down the misery rate — but unfortunately, they are not off to a good start.

• Richard W. Rahn is chairman of the Institute for Global Economic Growth and MCon LLC.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.