Combating China’s aggressive economic and military moves has become one of the few issues capable of forging bipartisan consensus in Washington.

Whether former President Donald Trump — who made confronting China a top issue in his 2016 campaign and then a cornerstone of his foreign policy in the White House — gets the credit for uniting the country against Beijing is another matter.

“Trump deserves the credit for this movement,” said Sen. Bill Hagerty, who served as an ambassador to Japan during the Trump administration.

“If you asked any man or woman on the street here in America, they would tell you China is the greatest strategic threat we face. If you asked that question in 2015, you wouldn’t get the same answer,” the Tennessee Republican said.

Democrats don’t see a direct correlation.

“China has been a growing power for a long time, they’ve gotten more aggressive against our values and trying to export that, particularly, with the Belt and Road policy,” said Sen. Benjamin L. Cardin, Maryland Democrat, referring to China’s global infrastructure development policy that targeted investments in roughly 70 counties since 2013.

“I think it’s been a growing problem that’s been addressed by all administrations, but it’s a growing problem that’s just worse today than it’s ever been,” Mr. Cardin said.

Still, the newfound bipartisanship on confronting China is remarkable given the deep partisan divide on nearly every other issue tackled on Capitol Hill.

The unity was on display when the Senate recently passed the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act, formerly known as the Endless Frontiers Act. The legislation boosts investment in science and technology research to counter Beijing’s growing dominance in microchip manufacturing, cybersecurity and other high-tech fields.

“Passing this bill … is the moment when the Senate lays the foundation for another century of American leadership,” said Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer, a New York Democrat who helped author the bill.

In total, 18 Republicans voted with 50 Democrats to approve the legislation. The 32 Republican senators who opposed the measure, including Mr. Hagerty, did so because they said they believed it did not go far enough.

“Needless to say, final passage of this legislation cannot be the Senate’s final word on our competition with China,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. “It certainly won’t be mine.”

The Kentucky Republican attempted to strengthen the bill before ultimately voting for its passage without the tougher measures.

Just a few years ago, Republicans and Democrats both had a different line when it came to Beijing. Many in the U.S. had long viewed China as a burgeoning market for American-made goods rather than an economic and geopolitical rival.

President Biden, when he was vice president in the Obama administration, showcased the friendlier view during a White House summit with Chinese functionaries in 2011.

“As a young [elected official], I wrote and I said and I believed then what I believe now, that a rising China is a positive, positive development, not only for China but for America and the world writ large,” he said.

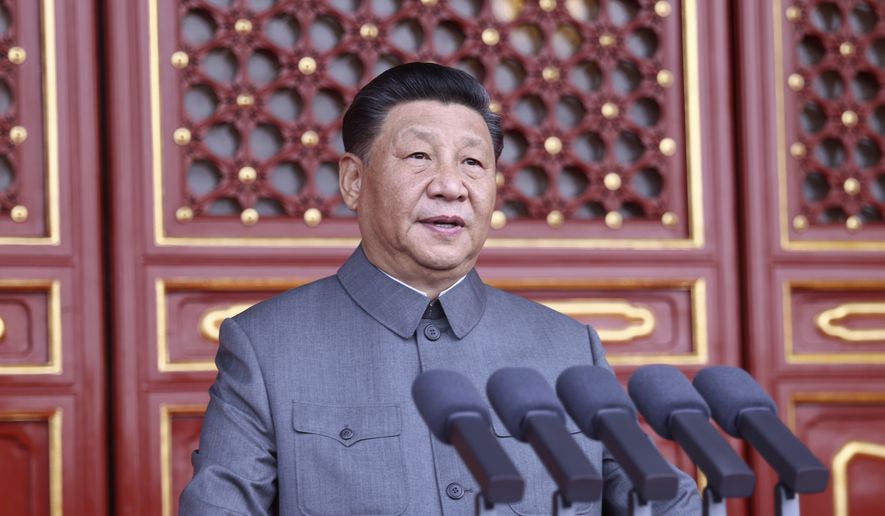

A decade later, Mr. Biden’s rhetoric, along with that of most in Washington, has changed drastically. In February, after holding his first phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Mr. Biden warned lawmakers: “If we don’t get moving, they are going to eat our lunch.”

It was an abrupt turnaround from his comments just two years ago on the campaign trail when he scoffed at Mr. Trump’s hard line on China.

“China is going to eat our lunch? Come on, man,” he said at an Iowa event in 2019. “I mean, you know, they’re not bad folks, folks. But guess what? They’re not competition for us.”

The shift can be attributed to two factors: China’s brazen misconduct on the international stage and Mr. Trump’s unrelenting China-hawk rhetoric since he entered the political arena in the 2016 race.

Throughout the 2010s, the communist regime in Beijing flaunted its subversion of global financial markets and gamed the World Trade Organization — almost entirely without consequences from the U.S. or other leading nations.

Most notably, China — which has the second biggest economy in the world behind the U.S. — has used its “developing nation” status in the WTO to protect domestic industries from foreign competition with high tariffs, while simultaneously being eligible for low-interest foreign loans. China has then turned around and offered the money from the loans at much higher interest rates to poorer countries in Africa and South America to fund infrastructure projects.

Developing nation status has also allowed Beijing to skirt compliance with many of the international climate change regulations it agreed to as a signatory to the Paris climate accord.

More often than not, the U.S has been a direct victim of China’s policies. For instance, the communist power endeavored throughout most of the early-2010s to flood the U.S. market with artificially cheap steel, undercutting domestic competitors. The result is that China has been able to conquer most of the global steel market, while the U.S. steel industry has been hit hard.

While China’s transgression had long been visible, it was Mr. Trump who pushed it to the forefront of public discourse. In his successful 2016 campaign for the White House, he lambasted Beijing as a “currency manipulator” and a purveyor of “unfair trade practices” that were crippling the American worker.

“Donald Trump really put China on the political map in very clear and concise terms,” said Christian Whiton, a senior fellow for strategy and trade at the Center for the National Interest, a conservative Washington think tank. “He showed that we were losing strategically and economically to Beijing and that the tale of China’s rise being peaceful was fiction.”

Once in office, Mr. Trump pursued hard-line policies, placing tariffs on Chinese goods and seeking to hold Beijing accountable for its unfair trade practices. The issue resonated, in particular, with blue-collar workers, many of whom previously supported the Democratic Party.

That political realignment forced both Democrats and Republicans to take a tougher stand on China.

“To the extent that Biden is tough on China, it’s because his people pragmatically realize that 2016 happened and the American people have shifted dramatically,” Mr. Whiton said. “Whether or not that leads to a coherent policy towards Beijing is yet to be determined. If it does, it will be driven entirely by domestic politics and in that case, as much as Biden may desire it, they can’t pretend that Trump didn’t happen when it comes to China.”

• Haris Alic can be reached at halic@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.